The “Little Project” at the Minnesota home of the firm’s founder creates experiences that exceed a small footprint.

By Lauren Mandel, ASLA

Voluminous hydrangeas bow gracefully over a pair of black chairs, barely grazing a stack of books that includes Planting in a Post-Wild World and How to Love a Forest. Granite chips crunch underfoot as garden party guests mingle and kids rush to complete a vegetable-garden scavenger hunt. “I think it’s beautiful,” says next-door neighbor Lori Nyberg as two girls wearing butterfly wings scamper across a series of log steppers. “We’ve kind of watched it evolve, and it’s just been really fun to see how things have grown since then.” She is talking about the Little Project, a tiny yet highly inspired residential landscape in Summit Hill, a peri-urban neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota, known for its historic houses.

Landscape architect Wanjing Ji, ASLA, the project’s designer, hosts the garden party with her husband, Tianyu Wu, at their house less than three miles east of the Mississippi River. Ji busily refills pitchers of cucumber water and answers questions about the landscape as Wu beams, seeing so many people enjoying Ji’s work. Ji designed the landscape in phases, which were built in 2020 and 2024, with the primary goal of offering a means of social engagement to their young, shy daughter, including as an “attractor for other kids to play with her.”

Demarcated planting zones surround the balance beam. Photo by Ping Design LLC.

Demarcated planting zones surround the balance beam. Photo by Ping Design LLC.

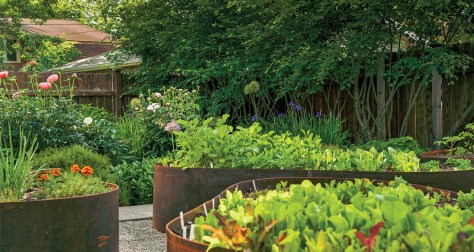

The landscape surrounding the family’s early-20th-century bungalow forms three distinct programmatic areas. The Little Prairie, which extends from the sidewalk to the front of the house, is a 1,010-square-foot natural playground that welcomes community play. Log steppers, a balance beam, a bench etched with the coordinates of the wood’s origin, and a reclaimed wood runnel offer opportunities for discovery, while a rain barrel and small rain garden enrich the landscape’s environmental performance. Behind the craftsman-style house and a modern addition, the Little Garden provides 800 square feet for a lounge area and pollinator habitat. Visible primarily through a large kitchen window, this space, designed for more passive use, offers seating for two nestled within lush plantings, including the hydrangeas. These are a favorite of garden party attendees Yanning Gao, Associate ASLA, Ji’s former colleague, and Suyao Tian, a fine artist. The third zone, the Little Farm, flanks the pollinator garden and lounge area and rests between the home’s primary bedroom and detached garage. This 840-square-foot space includes a carpentry deck, a dining table and chairs, a grill, and wedge-shaped weathered-steel raised vegetable beds, the landscape’s pièce de résistance.

After working for more than a decade at Coen + Partners and in China, Ji designed the Little Project, helping her kick-start her own firm, Ping Design LLC, in 2024. Ji grew up in the Inner Mongolia region of northern China; the name “Ping” comes from the Mandarin character ping, or píngcháng, which means “ordinary.” The firm’s mission is to “create the extraordinary from the ordinary.” “I want to bring what I learned through high-end or high-budget kind of projects to the everyday spaces,” she says, to “elevate people’s experience in those spaces and expose them to the possibilities.”

Minnesota’s short growing season means that winter interest is essential. Photos by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography, left; Ping Design LLC, center and right.

Minnesota’s short growing season means that winter interest is essential. Photos by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography, left; Ping Design LLC, center and right.

Before Ji began the Little Project, an underused lawn dominated the site with a foundation planting of shrubs and a maple in the front yard that had sent its roots into Ji and Wu’s sewer lateral. The site also received runoff from a neighboring property’s downspouts, which made its way into the basement. “It all started with dealing with thinking about water and then expand[ed to thinking] about water treatment,” recounts Ji. “Okay, rain garden: What else can we do to make it fun?” From there the idea for the rain barrel and runnel emerged.

Now a hardscape armature organizes the site, with strong geometry and clean lines that draw clear inspiration from Ji’s years at Coen + Partners. While the materiality of these lines varies—concrete, wood, granite chips—their purposeful placement elegantly interconnects the programmatic zones. In strong contrast to the hardscape, horticultural biodiversity brings beauty and messiness to the composition. This element brings the landscape to life and provides visual continuity between the zones. Ji’s attention to bloom time, foliage color and texture, and horticultural structure creates a true four-season landscape that bucks many residential trends and contrasts with the lawn-dominated landscapes of her neighbors. “I think it reflects Wanjing’s personality and who she is, and what she’s hoping to do, and [invites] people in with something new and something different,” says neighbor Paul Nyberg.

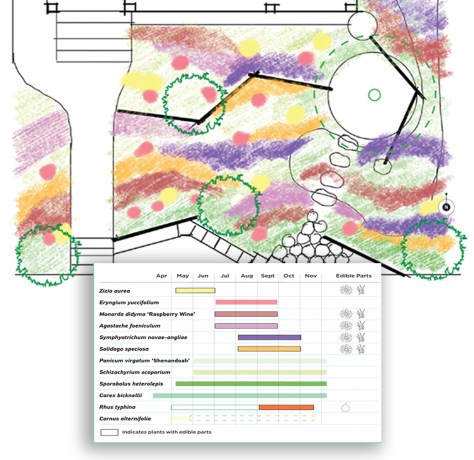

Ji’s planting diagram emphasizes seasonal interest and edible species. Image by Ping Design LLC.

Ji’s planting diagram emphasizes seasonal interest and edible species. Image by Ping Design LLC.

Ji’s use of reclaimed metal panels from a nearby church and black locust wood from locally felled trees further distinguishes this residential project. The metal panels, which were perforated for their original purpose, now function as retaining walls within the Little Prairie; one doubles as a bench backrest. Reclaimed wood also creates the adjacent log steppers, balance beam, etched bench, and runnel.

“I started to really get into recycled material,” says Ji, referring to her time working in Yunnan, China, in 2016 and 2017. Ji explains that material reuse is common in Yunnan due to the region’s traditional design methodologies and the creativity required when the desired materials are hard to source. However, back in the United States, she encountered challenges when trying to replicate the process for commercial projects. “There are very few people who actually stock reuse materials or resources,” she explains, which makes it difficult to specify a material’s exact properties. Ji overcame this limitation and was able to use reclaimed materials for the Little Project by specifying dimensional ranges and three acceptable wood species. She advises that being open and adaptive during the construction process is key.

The wood bench contains etched coordinates of the tree’s origin. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

The wood bench contains etched coordinates of the tree’s origin. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Using common or even waste materials

in unexpected ways can create an

extraordinary result.

Another linchpin was meeting Brian Luedtke, a local arborist and the owner of Holistic Tree and Forestry. Standing over six feet and wearing a reflective work shirt and rain boots, Luedtke

offered a warm welcome when I arrived at his shop. The reclaimed lumber stockyard and woodshop are in Andover, a rural area 30 miles north of the Little Project. Luedtke says that when landscape architects specify reclaimed lumber, “You need to know your wood.” In Minnesota, white oak, bur oak, and black locust (which is actually a noxious weed in the Upper Midwest) are the most readily available rot-resistant species for exterior applications. Specifying the degree of debarking is important, as well as “the finish grade of the cuts—can it be chain saw coarse, or does it need to be sanded smooth?” Better yet, he advises drawing the log you envision for your project.

Luedtke’s reclaimed wood stockyard and the reclaimed metal raised beds. Photos by Ping Design LLC, left and right; Lauren Mandel, center.

Luedtke’s reclaimed wood stockyard and the reclaimed metal raised beds. Photos by Ping Design LLC, left and right; Lauren Mandel, center.

Luedtke has an encyclopedic knowledge of his 2.7-acre stockyard, readily reciting each log’s species, age, and arrival date. He easily visualizes the best use for each log, from stump seats to runnels. “I plan all the cuts ahead, and then we engineer the rigging to harvest the parts,” he explains. “Everything gets used.” Most items are cut to order, so large piles of red oak and green ash logs abound at the stockyard, interspersed with piles of less common red maple, white pine, bur oak, hackberry, and spruce.

Luedtke’s fascination with trees runs deep. “I got really into bonsai right out of high school and had a big collection,” he recounts, which ultimately led to a degree in urban forestry from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and an interest in permaculture. Luedtke says that Holistic Tree and Forestry offers a systems approach to tree care and woodland management aimed at homeowners, private institutions, and municipalities within a three-county area. Luedtke particularly values park projects, especially when municipalities let him keep logs after he removes limbs or trees. “No one else keeps the logs, so if they have good logs on the trees, then usually they give us those work orders,” he explains.

Ji and Tianyu Wu’s daughter running through the Little Garden. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Ji and Tianyu Wu’s daughter running through the Little Garden. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

The Little Project was Ji and Luedtke’s first collaboration. The arborist says, “It was a dream.” Certain aspects were tricky, such as cutting an irregular pentagon out of reclaimed lumber that abuts the etched bench without a jig, or clamping the balance beam’s overlapping segments, but Luedtke says he enjoyed the challenge. “We’re building [for] somebody who’s going to grow up touching and playing on this stuff,” he says, referring to Ji’s daughter. “I was out here giggling at myself all day working on [the runnel] because I was just imagining the little boats going down it and the little waterfalls between the layers—that was an absolute blast.”

Above: The Little Garden, on the left, abuts the Little Farm at right. Inset: While not native, Siberian irises offer a pop of color. Photos by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Above: The Little Garden, on the left, abuts the Little Farm at right. Inset: While not native, Siberian irises offer a pop of color. Photos by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Brian Nelson, the contractor on the project, was the third member of the team. Nelson owns Nelco Landscaping, a design/build firm specializing in natural materials and rainwater management. He’s worked with landscape architecture firms for 15 years, but the Little Project was his first collaboration with Ji. Unlike a traditional design/bid/build project in which the design is meticulously documented, Ji prepared only plans, material schedules, and a SketchUp model. Nelson says this approach is typical: “The details are more or less kind of a collaboration of myself and the LA to figure out exactly how we want to build it,” which allowed for what he calls an organic installation at the Little Project.

For Nelson, the most exceptional part of the Little Project was the raised weathered-steel vegetable beds. “Bending them was a feat in itself,” Nelson recounts, that required using a rotating grapple on the front end of his excavator to bend the metal to the specified angles. Ji says that the raised beds are one of the project’s best moments because of the fun spaces they created and their relatively low cost. On another level, Ji explains that using common and sometimes inexpensive or even waste materials in unexpected ways can create an extraordinary result. “I think it’s the curation of how we use them,” she says. This process resulted in a surprisingly low project cost of approximately $33,000 for the Little Prairie and $18,000 for the Little Farm, including its carpentry deck.

Weathered steel raised beds provide fun and unique play spaces. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Weathered steel raised beds provide fun and unique play spaces. Photo by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Landscape architects can embed extraordinary moments with a curation mindset into a variety of everyday spaces beyond residential landscapes. Ji, Luedtke, and Nelson have already applied this process at a larger scale for a nature playground at Brooklyn Center Elementary School, just north of Minneapolis, in partnership with the Trust for Public Land. The project, which opened in August 2025, provides outdoor exploration using many of the same reclaimed play elements as the Little Project, with the addition of climbing logs and two play areas that double as outdoor classrooms.

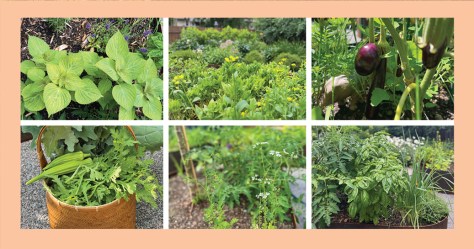

The small site yields bountiful vegetables and herbs. Photos by Ping Design LLC.

The small site yields bountiful vegetables and herbs. Photos by Ping Design LLC.

Back at the garden party, Leo Scott, age five, busily stamps insects and owls around an inked fern at a crafting table with Ji’s daughter nearby. The two have become friends; this is his second time visiting. He says he thinks the garden is pretty and notices the butterflies and bumblebees. Despite its compact size, the Little Project demonstrates how one landscape architect can help her daughter experience the everyday as extraordinary, enabling her to engage more easily in the world. But it also reflects a canny business decision. A small sign with Ping Design’s logo discreetly advertises her work to neighbors, while the garden party allows prospective clients to immerse themselves in her imaginative approach to landscape design. As Ping Design’s first built work, the Little Project serves as a calling card for the firm, earning a 2025 ASLA Honor Award in Residential Design.

Lauren Mandel is a Philadelphia-based landscape architect and director of design and innovation at Studio Sustena.

Project Credits

Landscape Architecture Ping Design LLC, St. Paul, Minnesota (Wanjing Ji, principal). Landscape Contractor Nelco Landscaping LLC, St. Paul, Minnesota. Arborist and Repurposed Wood Milling Holistic Tree and Forestry, Minneapolis.

Feature photo is by Lauren Gryniewski, Round Three Photography.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Comments are closed.