He says that, for him, naturalistic gardening was “a revelation”. It felt rebellious and like a “kind of anti-garden style that had no rules”. Even though you need to steer and guide, you have to relinquish some control.

Loading

This means accepting that some plants – even ones you really covet – will not work in the situation to hand. “It doesn’t matter how much you love gardenias if you live in the Tasmanian highlands, or species tulips if you’re on Sydney’s northern beaches . . . they will never make a home. Let them go,” Pilgrim writes.

Pilgrim himself lives in Newstead, a town in central Victoria with hot, dry summers and cool winters. The soil in his garden is dryer and contains more clay and more gum tree roots than his previous garden. This means that, despite all his pre-move propagating and even though he only shifted 13 kilometres, by the end of his first summer he had lost as much as half of what he had planted.

As deflating as this turn of events might be for you or me, Pilgrim’s response is best described as onwards and upwards. “I am over babying plants,” he says while we are sitting in his kitchen. “Even a plant tragic like me has learnt to say, no, I am letting go of that. It forces me to be a smarter, more knowledgeable plantsman.”

It also gives him more freedom to make his garden up as he goes. “If it was up to me I would change it every year.” All sorts of new ideas are “burned” into his brain right now because three days before we meet, he and his family returned from a three-month road trip in Central and Western Australia.

“I have been analysing the photos I took and diving deep into the planting rhythms, and thinking about how balanced the compositions were. The vastness really struck me, and the way the big sky highlights everything.”

His first weekend back he was outside with a can of spray paint marking our new paths and courtyards. He has been thinking about which local grasses might play the role of the spinifex hummocks that he loved in the Central Desert. He has also been ruminating about all the seasonal flowers and “successional spontaneity” that was bobbing up around them.

But context is everything when making any decisions about what to plant and where.

Pilgrim advises all gardeners to think about the aspect and orientation of their site, as well as its size and climate. “Look at your garden’s existing features and identify how you can make them work for you. What makes your garden special and unique?” he writes.

When it comes to small gardens, he says it is important to make them feel enveloping. And for those who only have a balcony? “You can still achieve this effect,” he writes. “Choose height – small trees, tall grasses – as well as shrubs and perennials, and fill your balcony with pots . . . to create a succession of features through the seasons, from early spring bulbs to late winter seed heads.”

As for very large gardens, including ones spread over hectares, he advises people to start gardening from the house and work their way out. “Pretend your house is a pebble that’s just been dropped in a pond and generated ripples. The first ripples are small and well defined, and as the ripples move farther, they get weak but wider. That’s where you bleed the naturalistic garden into the natural landscape.”

Pilgrim has ideas for every occasion and for every size of garden but his overriding piece of advice is to closely observe wild landscapes to get inspiration from nature.

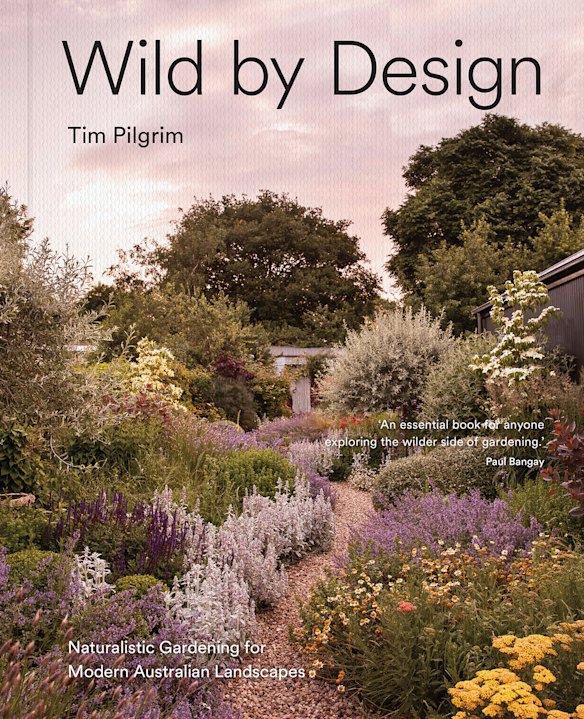

Pilgrim’s new bookCredit: Murdoch Books

‘Wild by Design: Naturalistic Gardening for Modern Australian Landscapes’ by Tim Pilgrim, photography by Martina Gemmola, Murdoch Books, $59.99.

Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Comments are closed.