See more gardening videos at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZEzoOaZqnfoVPUYtXji6wgWSrpzS6l7b

Find more videos at: https://www.youtube.com/user/ClackamasCounty

Live Stream: http://www.clackamas.us/cable/streaming.html

Website: http://www.clackamas.us/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ClackamasCounty

Twitter: https://twitter.com/clackamascounty

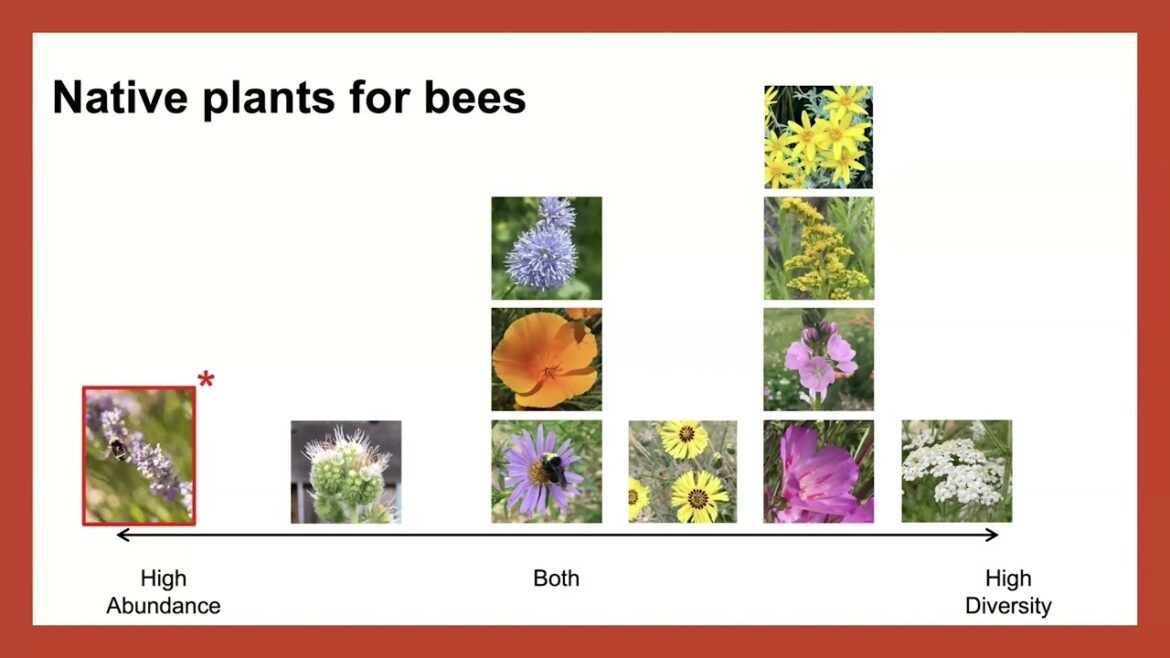

welcome everyone today’s session on native plants and bees is part of the let’s grow together 10-minute University webinar series our speaker Jen Hayes is a PhD candidate in Oregan State University’s horiculture Department Jen had to study pollinators in Vermont Ecuador North Dakota and Oregon I’m so glad she came to Oregon I’m delighted Jen will be sharing what her research in Oregon has revealed in the relationship involving native plants native R plants and Native B’s welcome Jen hello figuring out which keys are going to work for slide advancing okay here we go um um yeah thanks for the intro Sherry my name is Jen um I use she her pronouns and I am a grad student um I did my undergrad at the University of Vermont studying blueberries and raspberries and the services that native pollinators provide for them and in 2019 I started grad school here at OSU um and today we’re going to talk a lot about native plants and and how they relate to bees how they compare to Native cultivars and then the last section of my talk today we’re going to spend a little more time getting into some details about cultivars so uh to start and make sure we’re on the same page I wanted to provide the definition that we use for a native plant and so native plants are the indigenous terrestrial and Aquatic species that have evolved and occur naturally in a particular region ecosystem or habitat species native to North America are generally recognized as those that have occurred on the continent prior to European settlement and they res represent a number of different life forms including conifers Hardwoods shrubs grasses Etc and people vary in the scale that they use to determine a plant’s native status so here the native range of claria and moena is depicted in green on the map and while technically you could say this plant is native to North America or the Pacific Northwest it isn’t found across the entirety of those scales so even in Oregon you’re unlikely to come across the plant in the Central and Eastern portions of the state so scale is really important when talking about native plants moving right on to bees so while bees come in all shapes sizes and colors many people are only familiar with a handful of bees species such as honeybees and bumblebees and it’s important to note that these species are not representative of all bees honeybees for example are not native to the United States and they’re managed as agricultural livestock most native be species are not managed and their conservation concerns are often very different from the from those of honey bees so bees have diverse life histories and therefore they have different needs So based on their native status whether they’re social solitary or somewhere in between um the different nesting strategies they have and the different feeding strategies they have so we’re going to explore a few of those needs today as they relate to plants so what do bees get from Plants perhaps most importantly bees get food from plants so nectar is a combination of sugar and water which offers bees a source of hydration and energy if you want to help hydrate bees you don’t need to put out those little bowls with marbles you can just provide them with plants that produce nectar pollen is a source of protein fat and nutrients for bees and it’s eaten by some some adult bees but it’s primarily collected for their larvae to eat some bees also collect floral oils which can be used for laral Provisions as well so plants may also be important as Nest sites for bees around 30% of bees nesting cavities which can be provided by plant stems old logs Etc or others may have aerial nests that they use by um attaching them to plants and plants can also serve to provide protection over nesting areas in the ground or in other surfaces bees also collect many nonfood resources from plants which are typically used to help build their nests so things like sticks um this bottom left photo shows a bumblebee carrying a stick it’s called The Witch bee um and they also May collect plant hairs like wool Carter bees in the center photo here or resin from trees in the top right um a favorite example of mine that is neither shelter nor food actually comes from Orchid bees so that green bee in the bottom and male Orchid bees actually collect fragrances from flowers that they use to make a little perfume that they then um use to to help attract females for mating so we’re going to talk about native plants moving forward and how they might differ from another type of plant so native plants provide the same resources to bees that we’ve just discussed but they may be beneficial for other reasons as well so while non-native be species benefit from native plants these next examples are of particular importance for Native bees so native bees benefit from The evolutionary and geographic history that they share with native plants these benefits can include things like phology or timing so think of when chamelia Bloom this photo was taken in February which is several months from Peak B activity and while it may seem obvious that if you’re trying to plant for pollinators something that blooms in the winter might not be the best Choice timing can be incredibly important for bees most of which have very short lifespans so in deserts the emergence of some be species is actually induced by exposure to high humidity or rainfall so this indicates that their host plants have begun germinating so in environments with few floral resources the synchronous emergence of bees and flowers is often essential for their survival native plants may also be a better fit morphologically than some exotic plant species so bumblebees have longer tongues than honeybees which makes accessing nectar and blueberry flowers a lot easier for them honeybees are even known to nectar Rob from blueberry flowers where they’ll um make a little hole in the base of the Corolla to access the nectar instead of going in through the quote unquote front door of the plant and blueberries are also a great example because they have what are called per parisal anthers and so essentially they hide their pollen inside of the flowers anthers as opposed to something like lies where if you have them in a vase you’re probably very familiar with the pollen that readily falls off of those anthers so in blueberries to access the pollen bees have to shake the anthers through Buzz pollination which is also called sonication so around 50% of native bees sonicate which allows them to vibrate flowers and access their rewards so this pollen then may be actually better preserved for Native species to access different B species visit different plants and their diet May actually require them to visit native plants so we Define diet based on pollen foraging since it’s a more specialized food source than nectar and so far nectar specialization has not been documented in bees so bees have either um Specialist or generalist diets Specialists collect pollen from a narrow range of plant species so this may be as specific as a couple of species or as Broad as only a couple of plant families on the other end we have generalists which collect pollen from four or more different plant families so an example of a specialist is the longhorned be melodis clarier which is a specialist on the genus claria so these bees will only collect pollen from Plants within the claria genus but again they may collect nectar from a much larger variety of plants on the generalist side we have most bumblebees where they are going to be observed collecting both pollen and nectar from a really large variety of plants native plants are important for bee conservation so research has suggested that the inclusion of native plants in pollinator plantings can expand the abundance and the diversity of the bee community that a garden can support in addition to supporting specialist species so while generalists may be able to forage from a really wide variety of plants it’s really important to have native plants to support native specialist bees which have only a few plants that they can collect pollen from I’m going to share some plants for pollinators based on Aaron Anderson’s research which is also published in an extension article that’s referenced here and so don’t try to take notes you can jot down the name or the number of this extension article if you want but if you registered for this webinar in advance you will be getting a document that has all of the resources that I show here so don’t try to scramble and write everything down um and I want to note that when we are figuring out what plants are good for bees we usually consider abundance or the total number of bees found on a plant as well as the diversity or the number of different species found on a plant so the best plants are typically those that support a high diversity not just a high abundance of bees and so Aaron’s research looked at V visitation to 23 different Pacific Northwest Native plants and these plants were in the top 10 based on their abundance and diversity they’re not placed in any particular order here but we have things like filia and gilia California poppy um Douglas Aster and claria which I will talk about incessantly today um Madia Oregon Sunshine Golden Rock Rose Checker malow and Yaro and if we were to order them here we have a high abundance all the way to the left so an example of a plant that typically has a high abundance of bees as lavender which isn’t native but it’s a plant a lot of people are familiar with and tend to think of it as a pollinator plant because it typically is covered in bees in the summer and so while it might be buzzing it typically only has a couple of bees visiting it versus on the other end of this list here we have Yaro which is visited by a ton of different be species although at a much lower abundance moving towards the middle are plants that have a high abundance and a high diversity of bees and to be clear any of the plants that are listed in this top 10 would be great additions to a garden the point that I really want to emphasize is that when you’re selecting plants for your garden you want to make sure that you are selecting plants that support an abundance and a diversity of be species the plants that we just looked at were annuals or perennials and most of them were primarily native to Western Oregon so for any folks joining from Central and Eastern Oregon I wanted to highlight a couple of plants here for you as well so Yaro and Golden Rod are broadly native in Oregon um rabbit brush is another really great pollinator plant um east of the Cascades and that recommendation actually comes from the Oregon B Atlas and then for everyone in Oregon I wanted to point out another extension document which explores shrubs and trees for bees in Oregon and that’s based off of Scott Mitchell’s graduate research so a lot of these species are probably familiar um madrone Hawthorns and Willows Manzanita Choke Cherry as well as Copus and again these are resources available online and in some documentation that’ll be sent out after my talk so moving forward here we’re going to talk about the focus of my thesis re research which is native plants and Native cultivars so a visual example of a native cavar on the far left we have um farewell to Spring claria amoena the wild type and then to the right are three cultivars of that species and so typically we can identify a cultivar because it’ll have the scientific name of a plant followed by a name in single quotation marks sometimes you’ll have a full scientific name like claria amoena made in blush pink or sometimes it’ll just have the genus and so if it’s just the genus in front of the plant name that usually indicates that it’s a interspecific hybrid or that the parents come from two different species there have been several studies across the United States that have explored the use of native plants and Native cultivars by pollinators but the results tend to be mixed in terms of whether they find cultivars more less or equally supportive of pollinators as wild type native plants so we have people who have looked at perennials shrubs some very specific um group like milked and flocks and again that’s where this scale component comes in so what about B visitation to Pacific Northwest Native plants and cultivars so no study had been done in this region yet so that was the goal of my research to fill the Gap in our understanding about be visitation to native plants and cultivars in this part of the country and so for my project we selected plants that had commercially available cult devars um we included three perennial plants which are listed in the top here as well as two annual plants in the bottom row and the cultivars represent an array of plant breeding strategies so some of them are inter specific hybrids and some of them are selected from Wild populations a few examples here we we have Yaro in the top where both of its cultivars are interspecific hybrids um so is the Coline cultivar we list here Douglas Aster had both of its cultivars selected from Wild populations and then California poppy and farewell to Spring we have a bit of a variety of colors in those different annual plants so for three years we looked at pollinator visitation to our study plants in an experimental Garden in Corvalis and we used two primary metrics to quantify visitation so the first was observations where we would sit and watch a plant and record the types of bees and the number of bees that visited a plant over a 5 minute period we did this at least once a week when plants um had at least 25% of their Plot In Bloom and then our second method was collection so we use a vacuum interestingly to sample the bees that were actively foraging on Plants we vacuumed until no Bees were left on a certain plant and then we took them back to the lab where we were able to identify them to species and to sex for our observations we grouped be into five categories in an attempt to understand visitation by bees with different life histories so honeybees as we’ve talked about they’re social and non-native Bumblebees are social and Native longhorned bees are solitary and they have a high rate of specialization leaf cutter bees are distinct in that they carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen and they’re typically cavity nesting bees um and then we we have other bees which is kind of an amalgamation of the bees that we couldn’t easily identify from one another in the field which includes things like sweat bees and parasitic bees which also represent some other life history traits so using those 5B groups and all of our plants down at the bottom we’re going to build a heat map here to show you the results of our comparisons so we compared visitation by each B group between um the native plant in each of our plant groups and each of the respective cultivars so a green box will indicate that a comparison um that specific group of bees had a preference for the native plant white will indicate there was no statistically significant difference between the two plant types and then the purple will indicate a preference for the cultivar and so we’ll populate that here so really variable here as we can see there wasn’t any difference for any of the California poppies some of our plant groups had quite a few significant differences like the Douglas Esther and the farewell to Spring and then Yaro Coline only had a couple of differences so interestingly the um cultivars were only preferred outside of the Douglas Aster on two occasions so honeybees preferred um the salmon Beauty Yaro and other bees preferred the Scarlet um farewell to Spring versus all those other instances are happening here in the Douglas Aster group um and then on the other side there seems to be a clear preference for the native plant in the claria group aside from this one exception so we found that when there was a difference in visitation um bees were more likely to prefer native plants here the difference is 9 to7 though note that three of those cultivar preferences do come from honeybees which aren’t native and 9 to7 may not seem like a huge difference but these are only the results of statistically significant comparisons and what’s statistically significant can sometimes not reflect what’s ecologically significant so if we were to look deeper into these white boxes we might see some slight preferences for one plant or another um and these trends that we’re seeing here are also a little stronger when we include all of the pollinators that we studied but for time we’re only talking about beads today moving into our collection data across our entire research Garden we collected 70 different B species and when we look AC excuse me across our plant groups we see that the native plant in every group had a greater B species richness than the cultivars the magnitude of this difference is a little bit variable um the Douglas asers again seem to be a little bit more matched um versus the native claria had our greatest richness which was 29 different B species compared to its Scarlet cultivar which only um had nine B species visited we also collected five specialist B species but only three of them were collected in high abundance so more than 10 individuals so we found melodis clarier which is a claria specialist and then melodis lupinus and melissodes Mos dictus which are Aster Specialists um they did visit Yaro a little bit but not nearly in the abundance that they visited the Douglas Aster which is why we’re only talking about Doug theaster here so each of these species were collected more often from the native plant than any of the cultivars but again the magnitude of this difference is variable so our claria specialist we collected 11 times more of these Specialists off of the Native than we did from the second most visited plant dwarf white which only had 13 and then kind of on the opposite side there was only a difference in 10 individuals for melod micrus visiting the native Douglas Aster compared to Savi star the second most visited Douglas Aster so the general results we have so far are that bees were more likely to prefer native plants over cultivars um Specialists were more likely to be collected from native plants and the cultivars that were consistently preferred over their native plant types were actually some of the least developed cultivars in our study the next step for my own research involve exploring what plant traits might be driving those differences in visitation that we’ve observed so this is stuff that we’re actively working on right now but don’t quite might have results for so we’re going to be looking at floral rewards um where we analyze the nutritional content of the pollen from our plants as well as the quantity of nectar they produce and the sugar content of that nectar um if you’ve heard me talk before you’ve probably heard me mention um that leaf cutter bees collect petals from claria Plants to use in their nests so one thing that we have looked at already is floral resources of native plants and cultivars um by looking at leaf cutter B use of claria and so when Leaf Cutters come and take petal segments from claria and the bottom left image here you see these little crescent shapes that they leave and so over one season mallerie me an undergraduate student in lab LED our team in counting the number of flowers with evidence of leaf cutter petal removal across the four claria plants we had in our study um and then when we look at the number of flowers that had this characteristic Crescent cut shape we found that the native claria will had significantly greater usage by leaf cutter bees compared to the three Cult of ours and though we didn’t see any difference in leaf cutter be visitation to these plants there is a notable difference in usage of the plants for this nesting resource so leaf cutter bees then um may be affected by changes in Petal and leaf color of their preferred resource plants additional components of my research that we’re looking at our floral traits so Quant ifying the physical differences between native plants and cultivars that it might explain differences in visitation a couple things are pictured here which I won’t go into too much depth but um we have some graphs of the number of open flowers for claria just noting quickly here the scale of the axes so up to 800 for the native one versus Aurora um typically had less than 200 flowers open at any time um sea bresland another undergraduate student in our lab also took B Vision photos of all of our plants in order to see if the plants appear differently to bees um in those cases where you know we see a visual difference between a blue and a white flower but is that the same for bees which have a very different Vision than we do um we also measured plants in terms of the actual size of the flowers and then one thing that I’m working on right now is quantifying color and so each of these dots represent um a scan of a California poppy petal so I don’t really have much to say about all of this except that it’s in progress and hopefully it’ll be really cool um to tell you about when it’s done so finally I want to make a few points about cultivars because there is a really big growing misunderstanding about what cultivars actually are so first two terms to learn the first is genotype a genotype is the genetic constitution of an individual organism or the genes responsible for making a plant a certain way and then phenotype is the observable characteristics of an organism that result from the interaction between its genotype and the environment so phenotype are what we can actually see we can’t physically see the genes but we can see the phenotype that is created by those genes so here we have two pictures of Douglas Aster the most common native type is on the left so this purple flower so if you were going to a store during the time Douglas Aster was In Bloom and you had to pick out a plant that is probably what you’re looking for many plants though have naturally occurring variations in their phenotype a lot of purple flowers for example have naturally occurring morphs with white flowers so on the right here is a white morph of Douglas Aster it’s not the most common phenotype that you’ll find in Wild populations but it’s still a native phenotype for that plant species and so in our study we used a cultivar called Savi snow um a nursery collected seeds from a phenotypically white Douglas Aster from Savi Island they grew them out and then they gave the plant the name Savi snow so Savi snow is still a wild type native plant um it has a name it has a cultivar name but it’s just a less common phenotype of Douglas Aster parentage of cavars makes a pretty big difference so this is another example from our study um using Yaro so the cultivar we’re going to talk about here is ailia moonshine so moonshine is an interspecific hybrid um so its parents are Egyptian Yaro and then the species we know as Yaro and to get moonshine these two plants had to be crossed but in actuality it’s not quite as simple as the picture here so this is a ornamentally horticulturally bred plant so so while um ailia molum is in the beginning of moonshine’s pedigree there are a lot of crosses and generations that have happened between the initial cross and with what ultimately became the cult ofar moonshine so to compare these two cavars moonshine is a really distant relative of the wild type yarao but Savi snow is actually just as native as the purple Douglas Aster we used as the wild type in our study and so the point that I want to make here is some cultivars are just plants with fun names while some might be highly bred ornamental variants and so this makes the whole cultivar controversy a little more complicated because it’s often difficult to find out exactly where plants come from although some cultivars that are selected from Wild populations are advertised with their origin story so cultivars are often really appropriate plants to put in gardens um but your use of them might depend on your gardening goals so they can provide a source of color or beauty they may have resistance traits that aren’t present in wild or other variants of the species or they may have been bred to be smaller which might be more suitable if you don’t have a lot of space for plants in your garden there are some potential ecological concerns with cultivars those being um more highly developed cultivars and so that first concern is potential value to Wildlife which is the whole point of my study and this greater research on native plants and cultivars for a lot of plants we just don’t know if the cultivars are as attractive as wild type plants that’s something that we have some ideas about but there’s a lot of new nuances it’s not a very clear black and white one is better answer the other concern that we want to be aware of is potential spread into wild populations and this is also a concern with using non-native plants and Gardens so Lupin uh readily hybridize with one another which has caused issues for the threatened carner blue butterfly um and its host the Eastern Wild Lupin so the Eastern wild Lupin hybridizes with the Western big leaf Lupin or lupinus polyus which is also known as the Russell Lupin in horiculture so these butterflies can only develop if they feed from the Eastern wild loopin they can’t tell the what the Eastern loopin from the hybrids and if they feed on the hybrid plants they actually fail to develop and die and note that this example is relevant only for the range of the carner blue butterfly which extends from Minnesota to New York um if you have alarm Bells going off in your brain because Western Lupin is native to Oregon you can still use Western Lupin here in Oregon we just don’t want to plant it outside of its native range so for an example that’s a little closer to home um hybridization has been a concern with a Pacific Northwest Lupin as well although it doesn’t have an endangered butterfly host as far as I’m aware so Riverbank Lupin or lupinus rivularis um hybridizes with the invasive lupinus arborus and the plant is threatened in the northernmost part of its range so around British Columbia primarily and this invasive plant uh it’s invasive to the Pacific Northwest um from British Columbia down to California I’m not sure exactly its native range um but this is an invasive plant that is sold as both a straight species and as a cultivar and is actually available um to buy from a California based Nursery so this is my gentle suggestion to be really careful when you plant Lupin in particular but for many other plant species there’s actually very little information about their capacity to spread Beyond Gardens and then even beyond that whether they will um cross-pollinate with wild type plants and so as we’ve seen in the literature there are ecological benefits to cultivars some of them are visited more often than their native counterparts some of them have have um traits that are essential for maintaining plant species um and one other thing that we’re looking at in our lab is if cultivars or other plants that attract a high abundance but maybe low diversity of plant pollinators in gardens can potentially consolidate highly competitive pollinators and therefore leave other plants open to a greater diversity of pollinator species so this is a theory and a whole other can of worms um that I’ll probably talk about at some point in the future but so far our results seem promising um but anyway so getting into major takeaways from this talk Gardens for bees should seek to use plants that support a high abundance and a high diversity of bee species native plants May yield more benefits to bees than cultivars but cultivars are not without value and then cultivars that are more closely related to Wild type natives tend to be visited More Often by pollinators than highly bred cultivars and finally there is no one right way to garden and if you want some additional planting guidance this is your reminder to check out these two extension documents which again will be provided in a longer list of resources um and then from my own research I would in particular highlight all three of the Douglas Aster plants that we used um as well as um farewell to Spring and California poppy although note for those to I would recommend planting the native types because hybridization um might be a concern with those two annual plants and again if you registered for this webinar in advance you will be emailed a document containing all of these resources and if you didn’t I’m going to slowly tap through each of these slides in case you want to pause the recording in the future and type in one of these links so here’s page one page two and page three and then I want to um acknowledge all of the people who have helped me with my research so far including all of the undergraduate students in our lab past and present um link identified RBS and then of course um Gail for taking me on as a student um and my contact information is here as well as our lab website and our lab blog and I think we have a good amount of time to go through some questions well thank you so much for such interesting information and it’s uh fresh from your research uh my guess is not much of this have been uh included in Publications yet so we have a lot more to look forward to from what you’re doing um just to review so the best plant that we know from research from Oregon state would be those two extension documents one on annuals and perennials the other one on trees and shrubs folks are going to get this list and I used to look up you know um the best list of pollinator plants from a whole bunch of organizations and you know gardening magazines and later on I read most of those lists are not based on research and there is evidence that some of the lists are just copying from other lists um so can you say a little bit more about what you know in terms of the quality of information of these pollinator plant lists out there yeah I mean you you covered most of it I would say generally the best sources for that kind of information will be universities or like other organizations like the nrcs uh fish and wildlife um and in particular with native plants when we are really thinking about scale you want to be using something that is not just a North American Native Plant and so getting local resources local planting lists is a little more important um than something that is just native to North America now in terms of whether a plant is native to a geographic area I know in Oregon we can use Oregon Flora as a um trusted Source but I know in the United States we can also use a USDA plant database um I don’t think we included a uh a website for that but maybe we we should add that uh do you have a personal experience using both uh is there anything you want to say about which one is better ease of use Etc um Oregon Flora is still being updated so it doesn’t have the range maps for everything I usually use both okay yeah all right um and then there are a lot lot of questions about how do we know which is really a native plan as opposed to you know just by looking at names so I know you wrote something that summarize you know what’s in a name when you look at a name to decipher a plant’s origin and also how to buy natives would you elaborate a little bit the main points from both yeah so there’s a naming convention that we can use to identify cultivars um but of course it is a little more complicated than that so often if something is marketed as a straight species we would hope that it is a straight species and not a cultivar um so that is maybe the easiest or most direct way to buy a native plant if you’re concerned about it being marketed poorly or like incorrectly there are some nurseries that um verify like the origin of their plants but um going to a native plant nursery um will usually be a little bit more specialized and you will probably have less questions about if a plant is a native type or not in the case of cultivars of native plants it requires a lot of research unless the plant has like a website page where its origin is described and so with Savi sky and Savi snow the nursery we got them from it says in their description that they are selections from Savi Island um I know there’s a couple other ornamental plants that have their or other cultivars of native plants where it’ll say like Jean Sullivan found this plant on the side of this River in Kentucky and that’s like part of the description but it’s not always that clear sometimes it takes a little bit of research to figure out whether a cultivar is has a cultivar name because it’s very different from the native plant or if it’s just a representative of a less common phenotype so it’s it’s not a simple process but yeah um as we raise these issues and kind of figure out what is being named what I think hopefully moving forward um plant labeling can hopefully become a little clearer yeah I I agree um in your research have you come upon any resources that uh clarify among the flowering commonly grown flowering plants and Gardens which ones have better nectar resource or in terms of abundance uh or quality and which ones have better pollen resource also quantity and quality um so this is an area that is still being actively researched um I know that um the honeybee lab and um priia who used to work in the honeybee lab is now at Mississippi State and so they have a collaboration with some funding where they’re trying to get the pollen new nutrition for a really really long list of plants and so that is a resource that I think is going to be coming out in the next two years um and I think aside from that there are scattered papers that have pollen nutrition data but they’re it’s it’s pretty limited and um different bees have different nutritional ratio preferences for pollen too so again it’s not quite as simple as here are the plants with the most protein because some bees want a little less protein um and then nectar I also don’t know of a great resource that’s out there um yeah I think that’s something that’s still a little ways away although typically planting something that produces both nectar and pollen is a great way to just cover both so things like Aster produce nectar and pollen California poppy doesn’t produce nectar but it produces a lot of pollen so just making sure that both of those resources are represented in gardens as some capacity is good that sounds good we have some people who are asking questions about growing California Native which also can grow in gardens in Oregon uh what’s your view there er a lot you got to decide the scale for yourself um I think and also like I think many of us probably have nonnative ornament mentals in our Gardens already so Gardens you know are spaces that can be for conservation but they can also have other purposes like I’m sure most of us have basil and tomato like getting ready to go into the garden and neither of those are native to Oregon either but we aren’t going to remove them so again it it comes down to what your goals with gardening are if you want to focus on supporting pollinators including some Oregon natives with Pacific North other Pacific Northwest Native plants um can be a good option but you don’t have to be one or the other you can have non-natives and Natives and things that are almost native um depending on your definition sure uh would you say a little bit about what you know the relationship between honey bees and Native bees I’ve heard that honey bees may be uh keeping native bees from getting enough food if there is too much competition in the garden uh what do you know from research so this is one of those areas where there is a bit of mixed results but ultimately it comes down to the abundance of honeybees and the abundance of floral resources so in areas where Floral resources are scarce and there’s a lot of honeybees there is likely going to be competition between wild bees and honey bees in areas where there are a lot more floral resources to choose from there could be um a little competition like if if you have a tree that is blooming and it’s covered in honeybees that might be like a short-term competition because honeybees have the capacity to communicate with one another about like great floral resources so they may like monopolize like a big resource but again that’s less of a concern if there’s tons of other things flowering in the landscape so generally I would say they can and do compete with Native bees in certain spaces so the message to gardeners is grow more flowering plants long season of Bloom abundance as much as possible but also in diversity flower shape color Etc and making sure there’s more than one thing blooming at a time for each season and again this is like if you have the capacity to do that maybe you don’t that’s a CLE of plants in your presentation that jump out at me one is the claria it seems like it just does so many interesting things and it supports specialist bees so this is something that I made a note I’m going to be growing this year um but if I go to the nursery buy claria that does not have a cultivar name because I want the straight species based on your research is supposed to be better um I grow it out is the only way I can tell whether it’s a straight species uh when it Bloom and by looking at the flower pattern that is the easiest way okay um we have some plant so we have the native and the cultivars and there has been some hybridization we haven’t been able to tell if it’s just the cultivars Crossing with each other or if the native is also Crossing with the cultivars um and with some of those if you’ve been staring at the plants for four years you can tell by the vegetation because the cultivars the ones we have at least um they’re a little shorter and everything about them is a little bigger um but if it’s your first time growing a plant it’s probably not going to be super easy to tell unless it flowers okay so it may be a good idea for me to not grow cultiv bar and the straight species in a close proximity if I want to grow claria I should just try one thing first and and you know gain some experience before uh expanding yeah it’s one of those plants where we’re a little worried about potential escape from Gardens so prioritizing the native claria would be great and it is such an interesting and important pollinator plant um so I feel like that’s justification enough and it’s it’s a beautiful little pink flower great Cut Flower well I’m looking forward to trying it um do you know much about Sedalia which is also a nice native perennial easy to grow uh can you give some advice on maybe adding that to the Garden yeah I we had Sedalia in my study but the cultivars turned out to not be related to the native plant at all so it got removed but um Sedalia plants have continued to germinate every year even though we keep removing them so um also great in um longevity there and um there are also a few Specialists on SED Delia um specialist bees so it’s a nice early spring perennial that is pretty resistant to you trying to remove it and support some Specialists that sounds great I think I’m I’m going to add sedia it’s the common name is Rose cheero and uh claria the common name is farewell to Spring uh I think I’m G to add these to my garden this year just try a little bit of uh different things every year to make the garden more pollinator friendly um any um final words for our folks we’re going to be wrapping up this webinar uh you talked about looking at pollen nectar and flower structure uh next in your research uh would you say a little bit about what are the main gaps in our understanding of the relationship between bees and flowers plants it’s just it’s a very complicated story with a lot of asterisks to anything you might find so it’s I think getting the trait data is going to help us better understand why some patterns might be happening um but um yeah it’s it’s a little too early to say anything really okay um yeah it’s it’s unclear whether one trait is more important over another um and I think that’s going to take a lot of additional research to determine and I guess we should wrap up by suggesting everyone to check out the garden ecology Lab website which is Garden ecology. orgon state.edu we’ll put that in our resources because that’s where research done by Jen and others associated with the lab uh will appear over time as new information becomes available and with that I want to thank everyone for joining us and next week we’re going to talk about plants for a nonirrigated landscape before the hot weather comes that uh may be useful information for many of us who gardening this area thank you very much Jen for giving your time and sharing your knowledge today we have a lot of folks um saying how much they enjoy the information and um that’s it folks until next week