I am sitting on the lawn in the sunshine. The grass is cool and green and bristly. I don’t move, because I’m still a baby and the world comes to me. The dog approaches, sniffing. She has a wet black nose. She has a curled tail. She has fur the color of butterscotch. I’m not afraid of her, and I put out my hand. I call her “Ginge,” though her name is Ginger. She is my first memory.

What I remember about Ginger is that she is old. My brother and sister are both ten years older than I am and she is older than the both of them. She is as old as my parents’ marriage. My father tells the story of surprising my mother with her when they were newlyweds living in Brooklyn, back in 1947. “I kept her under…my coat,” he says, in his characteristic speech pattern, his melody of pause and dramatic emphasis. She was a mutt, a mongrel puppy owing half her bloodline to a type on its way out of popularity in the United States—the spitz. There are ancient photos of my parents with her, just the three of them together, and even when she’s sniffing my hand on the lawn of our split-level on Long Island, she’s simultaneously a denizen of the distant past. She’s a living fossil, an artifact of that personal Pleistocene when my parents loved one another and had a happy marriage. She has more right to be there than I do.

I was three years old when my father had an affair with the mother of my first friend, with whom I shared a crib as a newborn. My parents were never happy after that, and to love both of them required me to surrender to warring impulses. I was my mother’s ally and confidant and lived in fear of my father. And yet I could never get enough of his stories, especially the ones about dogs. The stories he told about his days as a street tough in Brooklyn made him out to be invincible, and the stories he told about his days as a big-band singer in World War II confirmed my suspicion that Lou Junod was like no other human being on earth, never mind the workaday dads who commuted back and forth to New York City on the Long Island Rail Road. But my father was tender when he talked about dogs. He was vulnerable. He was a boy, just like me.

One of the stories I asked him to tell again and again was about a Doberman that lived around the corner. It was a fearsome dog tethered to a short chain, but my father, alone among his cohorts, befriended it and won its trust. One day the dog snagged its eye on an exposed wire, and my father attempted to clean the wound with a hose. “Its eye was hanging out of the socket, and the dog…went for me.” He never said what happened, if he got bitten. He just made a strange sound, a cross between a yawn and a gargle—“Yaaaaaargh”—and opened and closed his fingers like snapping jaws right before he grabbed me by the wrist.

Ginger died when I was five and she was sixteen, the last inhabitant of Eden. We got another dog, Nikki, a silver-and-black German shepherd, with papers. But Nikki was never my dog. As Ginger was my father’s dog, Nikki was my brother Michael’s, the tales of her devotion to him essential to my family’s mythology. The time she broke through a window screen at our summer home and swam out into the bay where he was water-skiing! The time she showed up at a nighttime bonfire he was attending on the beach a mile from our house! When Michael left for college, I was all of eight years old and pushed my face up against her snout, whispering, “Looks like it’s just me and you, girl.” She bit my nose, a fact that never became part of the family mythology because I stored it in my personal repository of family secrets.

When I was just entering adolescence, Nikki began suffering from terrible diarrhea, and my father took her to a vet. She stayed for nearly a month. She had cancer, the vet said, and when my father went to check on her, he was presented with a bill for thousands of dollars and a dog so emaciated she couldn’t walk. My father picked her up and carried her to the car. The vet tried to stop him and make him pay the bill. “Put your hand on me again and I’ll kill you,” my father said, and took Nikki to a vet who did the obvious thing and dewormed her. “There was a ball of worms in her stool the size of my fist,” my father said. Then he slept next to her and fed her by teaspoon and eyedropper for four days, and to this day, when Michael talks about my father—about what a good man he was—he says, “He saved Nikki’s life.”

I did not get a dog of my own until I married Janet and we were trying desperately to have a child, and I came home one Christmas with a rottweiler puppy. Her name was Willie, and when Janet’s dad saw me walk through the door with her in my arms, this sometimes dour man allowed himself to look abashed and delighted, smiling through pursed lips like a little boy. My mother reliably offered her face for Willie to kiss. And my brother’s embrace snapped me out of a state of shock after a car later ran her over right in front of me.

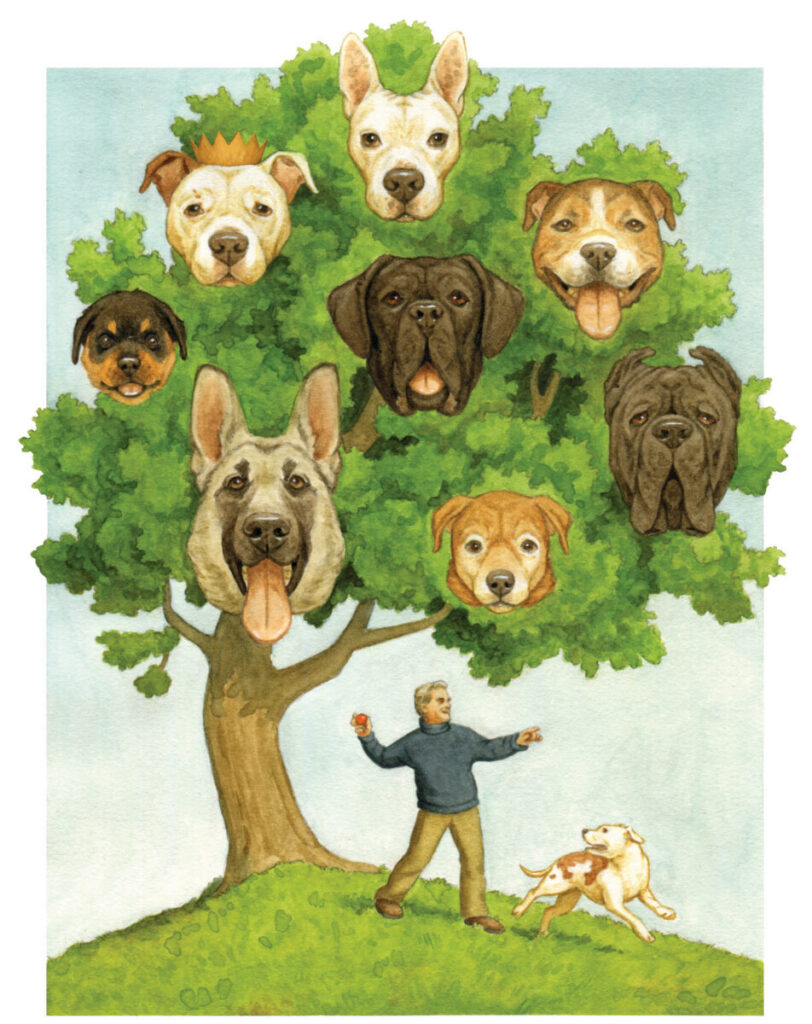

I do not remember my father with any of my and Janet’s dogs—how he treated them, what he said about them, how much he liked them, whether he approved of them. The dogs I grew up with, Ginger and Nikki, were not my dogs. They didn’t just belong to my family—they belonged to my family’s stories, over which I had no control. But somehow, I turned out to be my family’s dog guy. As a family man, as a husband and as a father, I have had six of them, and like my dad, I like domesticating the ones with a reputation for ferocity. We have had a rottweiler, two cane corsos, and three pit bulls. Willie. Hawk. Marco. Carson. Dexter, the king. And now Jacques. One of those dogs came from a backyard pen where he was so neglected he kept falling down into his own waste; three of them from the shelter. I cried when the first five of them died almost as hard as I cried when my brother called me at 12:30 one morning to tell me my father was gone.

I’ve written a book about my enigmatic father and my family’s stories called In the Days of My Youth I Was Told What It Means to Be a Man. But in the days of my youth I was also told and taught about dogs, and as an adult I have come to believe that dogs and manhood are linked—that my dogs also tell me what it means to be a man. I’m good to them, kind to them, patient with them, gentle with them, and in return they have never let me down. Good God, my father had so many secrets, so many lives outside of our family, that it’s hard to say he was a good man, one worth emulating in any way. But he was a good dog man.

And I am, after all, his son.

Comments are closed.