The bright red poinsettia has become a symbol of the holiday season, but its story follows a path from southern Mexico to South Carolina, to Southern California before an NC State Horticulture professor unlocked the secret that transformed how the plant is grown.

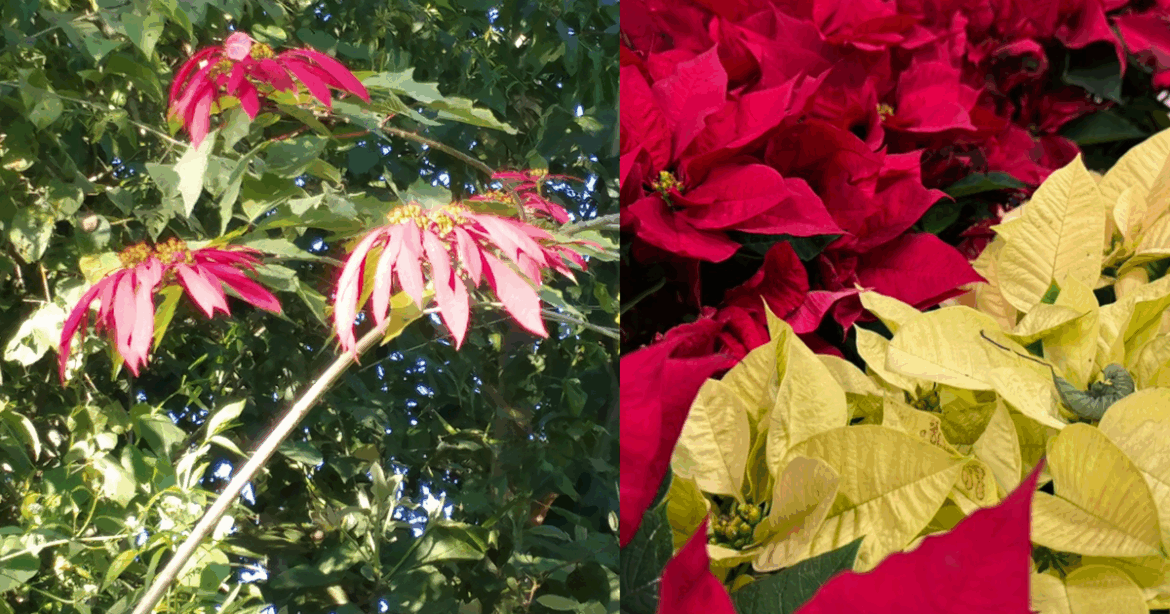

Poinsettias are native to tropical regions of Central America, where they grow as tall stalky shrubs along canyons and ravines. Wild poinsettias look very different from the ones you’ll find for sale in your local grocery store or home improvement store garden center.

wild poinsettias in Oaxaca, Mexico

wild poinsettias in Oaxaca, Mexico

Long before the plant became a holiday decoration, the Aztecs cultivated the plant they called cuetlaxochitl (kwet-la-sho-she) for centuries for medicinal use and red dyes.

In the 17th century, Franciscan monks arriving in Mexico noticing that its bracts (leaves) turned red during December, responding to the long nights that follow the autumnal equinox and incorporated the flowers into Christmas celebrations.

The poinsettia’s U.S. history began in the 1820s with Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first American minister (ambassador) to Mexico. Poinsett encountered the striking red plant and sent cuttings back to his Greenville, South Carolina plantation.

The plant spread through botanical gardens and horticultural circles, and in 1836, botanist William H. Prescott formally named it Euphorbia pulcherrima, though it soon became commonly known as the poinsettia in Poinsett’s honor. For much of the 19th century, poinsettias remained specialty plants grown outdoors in warm climates or solely in greenhouses.

The Ecke Family makes the Poinsettia the California Christmas Flower

In the early 1900s, the Ecke family established poinsettia farms near Los Angeles. They initially sold poinsettias as cut flowers, famously marketing them along Hollywood Boulevard in the 1920s and 1930s.

Popularity of “the Christmas flower” grew as the Eckes supplied poinsettia plants to the Tonight Show, Bob Hope’s Christmas Special and Good Morning America as well as the White House. By the mid-20th century, the Ecke Ranch supplied up to 90 percent of the poinsettias sold in the United States.

The Eckes had perfected grafting techniques discovered by Norwegian breeder Thormod Hegg that combined “free branching” with more “restrictive branching” varieties producing fuller more attractive, and more economical, plants. Selectively breeding also produced plants that could survive indoors for longer, transforming the plant from short-lived cut stems into durable potted plants suitable for homes and stores.

The popularity continued to grow thanks to Ecke’s marketing campaign which supplied plants to women’s magazines for their Christmas issues and to television shows like the Tonight Show, Bob Hope’s Christmas Special, and Good Morning America.

Growers like the Eckes as well as the the Heggs of Norway and producers in Germany and knew that grafting worked, but not why.

The Scientific Breakthrough

That mystery was solved in the late 20th century through research led by Dr. John A. Dole, a plant pathologist and horticultural scientist.

Dole grew up in West Michigan where he was active in 4-H, worked in a local dairy, and grew gladiolus for a local farm market. He continued his love of horticulture he earned a degree in the field from Michigan State before going on to an internship at the Ecke Ranch near San Diego.

Most theses, even those that earn the author a PhD, sit unnoticed on dusty shelves of the campus library. But Dole’s research, in part funded by the Eckes, titled “In Vivo Characterization of a Graft-transmissible, Free-branching Agent in Poinsettia” not only earned him that PhD, it was published in Journal of the American Horticultural Society.

Dole, a Professor of Horticulture at NC State has also served as Dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, still calls the poinsettia “One of the most interesting plants ever” in an interview this week.

The secret was out and it sparked a revolution in the poinsettia making mass production possible and transforming it to the top potted flowering plant in the U.S. selling more than 30 million each year between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Grafting plants was nothing new, apple and citrus growers use the technique to join desirable fruit to more disease resistant root stock. But the host tree remains just that, a host. Poinsettias are different. The resulting plant is different after grafting.

The research found that grafting transferred more than physical support from one plant to another.

Unlike grafting fruit trees—where the fruit remains unchanged—grafting poinsettias permanently affects plant shape, causing increased branching and compact growth. Dahl’s findings, published in peer-reviewed journals in the early 1990s, explained decades of grower observations and fundamentally changed poinsettia breeding.

Additional research by USDA scientists found a phytoplasma “trigger a hormonal imbalance responsible for forming squat, full-bodied poinsettia plants with many flowering branches”, exactly the kind of plants consumers want.

Metrolina Greenhouses in Huntersville produces more than 4 million poinsettias each year

Metrolina Greenhouses in Huntersville produces more than 4 million poinsettias each year

The discoveries enabled growers worldwide to reliably produce poinsettias in many colors, including red, pink,, white, cream, and green. It also enabled large-scale production, moving poinsettias from specialty florists into grocery stores and home-improvement centers.

Today, poinsettias are one of the most important flowering potted plants in the United States. North Carolina is among the nation’s leading producers. Metrolina Greenhouses in Huntersville, produces more than 4.4 million poinsettias each holiday season from the largest heated greenhouse according to the company.

But aren’t poinsettias poisonous?

Despite the myth that has persisted for more than a century, poinsettias are not poisonous.

The claim originated in unsubstantiated stories about the death of two-year-old child in Hawaii in 1919 after eating the plant. This account was later included by Dr. Henry Arnold in his 1944 book Poisonous Plants of Hawaii. Arnold eventually acknowledged that he hadn’t validated the claim relying instead on hearsay.

Multiple studies have also found that while there are plenty of poisonous houseplants, poinsettias are not one of them. “Toxin exposures in dogs and cats: Pesticides and biotoxins.” Published in the American Journal of Veterinary Medicine describes them as “nontoxic”. That milky latex found in can be irritating to humans and pets alike, but even when eaten, “mild gastrointestinal irritation” causes vomiting rather than anything more serious. A Purdue University study found that “if signs develop they are usually mild.” but recommends that plants be kept out of reach of animals that tend to chew like cats and puppies.

Poinsettia longevity tips from Dr. Dole

put them in a bright sunny location, near a winter windowPoinsettias like cooler temperatures, near the mid 60s, never near a heat sourceCheck the soil every few days with your finger tip. When the soil feels dry, add some water, but be careful not to over water.

Comments are closed.