On New Year’s Eve 2024, just as he had done every New Year’s Eve for nearly a decade, Paul “Pableaux” Johnson was preparing to feed his people. A social media post from that day shows Pableaux—a New Orleans writer and photographer and one of Epicurious’s “100 Greatest Home Cooks of All Time”—filling a shopping cart with big heads of green cabbage, andouille sausage, and bags of Camellia brand black-eyed peas. With hindsight, there’s a dark irony to the caption that I think Pableaux would’ve laughed at. “Kids, make sure you get your black eyed peas (for luck), cabbage/collards (for folding money) and cornbread (for gold). But mostly the luck. Don’t wanna take too many chances in ’25.” That night, as the revelers on Bourbon Street raised a toast to the new year, Pableaux had peas soaking in preparation for his traditional feast.

For New Orleans the year did not start out lucky. We woke on New Year’s Day to concerned texts and the gut-punch of the news about the Bourbon Street terrorist attack. We told our friends we were all right; mourned for our city and the reason for its return to the national stage; and considered whether or not we had the capacity to go out and gather at Pableaux’s.

By that time, he’d probably already been up for hours, slicing and caramelizing a heap of onions, dicing the pork he’d smoked himself to season his smothered cabbage (aka “pig-basted greens”), and tidying up his pink shotgun house. Sometimes you have to make your own luck. And Pableaux was doing just that, building it like a shelter with every ingredient he added to his big Magnalite pots. He had invited scores of people over to drop in throughout the day when they pleased, but in light of the news he didn’t know how many would come.

When we arrived, red-eyed, tentative, and hungry at Pableaux’s front door, he embraced us and ushered us in, ordering us to grab a plate while simultaneously taking care of three or four other guests. The house was packed, the food delicious, the conversations heartfelt. We had arrived discouraged and sinking and took hold of the food and each other like we were grabbing onto a life raft.

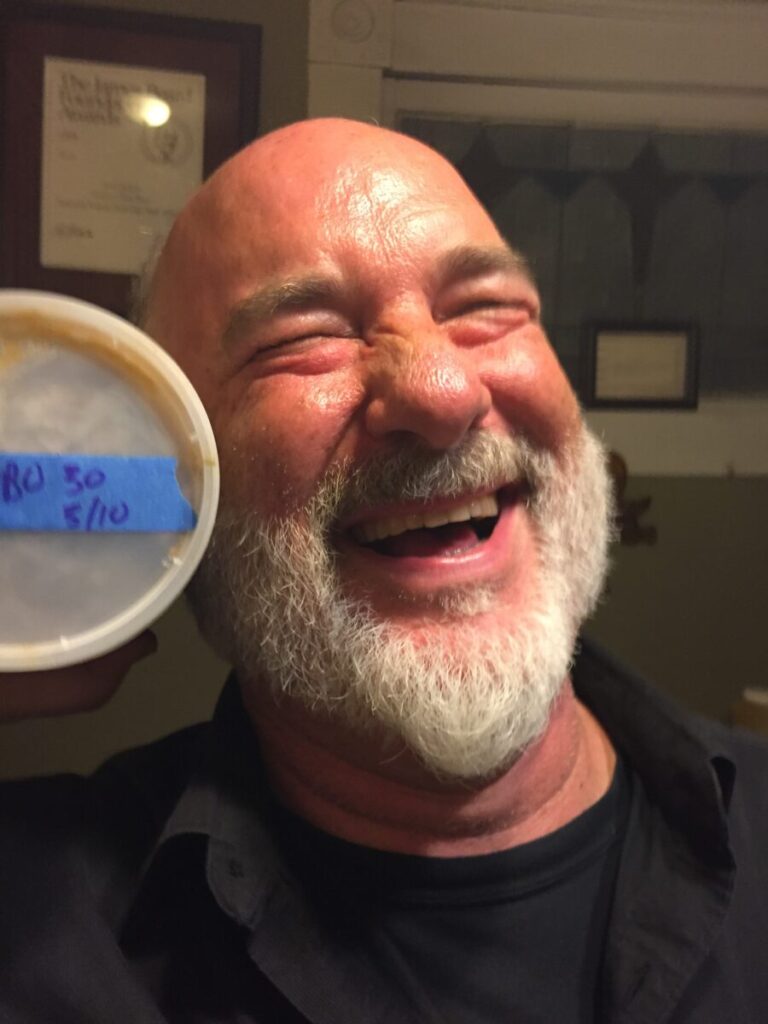

One of the guests, a photographer and computer engineer from India, invited us to his favorite restaurant, one he said made regional food that tasted like his grandmother’s. A shy truck driver who sat alone on a couch opened up to us about her love of superhero movies; said her uncle had persuaded her to come against her better judgment but she was glad she did. Pableaux—as good with a camera as he was in the kitchen—was famous for portraits of people in their most genuine moments. He let no one leave without first snapping a few photographs. Days or weeks later, he texted us those photos—a surprise moment of joy from a historically tragic day.

New Year’s 2025 in New Orleans didn’t start out feeling like a good day. But those of us lucky enough to know Pableaux have something else to remember it by, something crucial and light to place on the scales opposite those other heavy facts.

Now we are a full year out—most of it spent without our great friend there to care for us. Just weeks after that gathering, he was out photographing a second-line parade and had a heart attack. He was fifty-nine. Looking back at our bleary-eyed smiles in his photos, I’m overcome with a wholly new understanding of the power in the simple act of making food and inviting people over. The generosity of a soul-satisfying, delicious meal shared freely with your friends and neighbors. Acts like these can tip the scales.

Pableaux had sayings. One of his favorites was “Ain’t we lucky.” He made magnets with the phrase and passed them out. There’s one on my fridge. If I’m ever not feeling particularly lucky —if there’s an imbalance in the scales in the world—it reminds me of a way to make my own luck: Cook something homemade and share it with someone else. That’s it. Forge a connection. These recipes for Pableaux’s “good luck foods” represent the opportunity for all of us to do just that.

Comments are closed.