Why do we garden? Often cited as “America’s number-one hobby,” more than half of U.S. households are engaged in some form of gardening, according to RubyHome, a luxury real estate brokerage based in southern California. That’s 71.5 million households with a garden, with 18.3 million of those added in 2021, around the pandemic.

The average U.S. garden is 600 square feet and produces $600 worth of food.

A 100- to 200-square-foot food garden can feed one person year-round.

People garden 5 hours a week on average.

Tomatoes are the most popular homegrown vegetables and found in 86% of food gardens.

Surprisingly, just 29% of U.S. gardens are in the South.

But why? What motivates millions of people do sow seeds and get dirty? And especially in harsher climates like the North?

RubyHome reports that while 55% of people garden to create a beautiful space (it can boost property value), 43% garden to grow food. And of these, some are looking to help cut rising costs, some enjoy the time outside, or both.

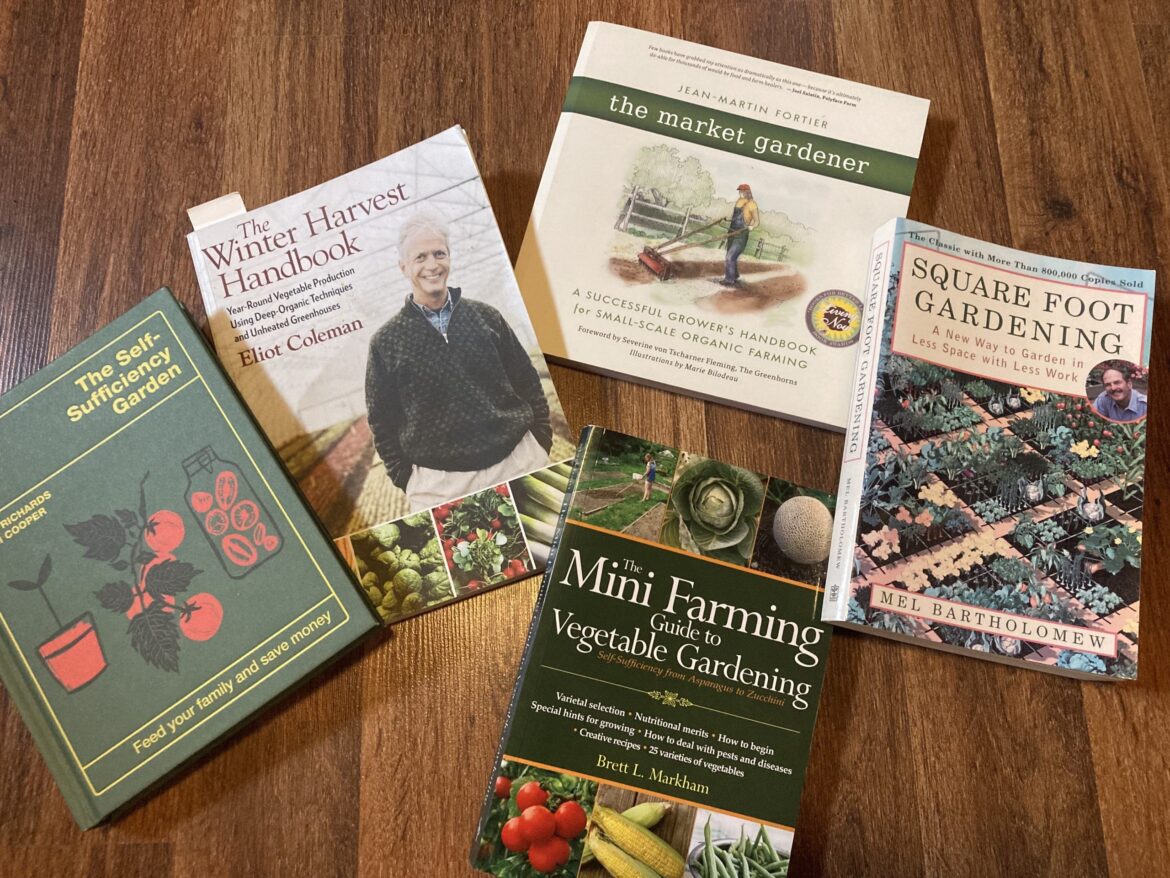

For Brett L. Markham, author of “The Mini Farming Guide to Vegetable Gardening” (Skyhorse, 2012), it’s “to prevent as much contact as possible with the medical community.”

In other words, for health.

Markham writes, “Study after study demonstrates that vegetables contain hundreds of important compounds to fight or prevent practically all chronic diseases, and links vegetable consumption with lower incidence of disease even in case which other adverse lifestyle practices are present.”

Yet, Markham notes, fewer than ten percent of Americans eat the recommended daily dose (about two pounds). According to him, this is because modern agricultural practices often create “tasteless downright unappealing” options. And that a family of four getting a modest three pounds per person daily can easily balloon a grocery budget.

“The Mini Farming Guide to Vegetable Gardening”, then, focuses on gardening for health and self-reliance. Chapters on soil and fertility, with sections on composting, raised beds, pH and nutritional composition, lay the literal groundwork. Subsequent chapters devoted to each of seventeen vegetables or vegetable groups chosen for caloric density, nutritional bioavailability, practicality, and ease of growth make this the perfect primer for the “prepper” gardener, and a great guide for any gardening enthusiast.

“Square Foot Gardening” by Mel Bartholomew (Rodale, 2005) moves deeper beyond the Why and the What to explore the How. Square foot gardening is a fairly well-known practice that forgoes the row-method of growing vegetables as inefficient.

Though the underlying principles of intensive, high-yield gardening in small spaces have been used by past cultures for centuries, Bartholomew’s square foot gardening is really the definitive system for biointensive practices anyone can use. With sections on vertical farming, the use of cages, boxes, and other supports (I especially appreciate the chapter on watering, as some gardening books run roughshod over this very important aspect or skip it altogether), “Square Foot Gardening” is as dense as the practice it clarifies, full of illustrations, photos, graphs, and graphics.

Huw Richard and Sam Cooper’s “The Self-Sufficiency Garden” (DK, 2024) is even more intense. The encyclopedic hardcover takes Markham’s motivations (optimal health, do-it-yourself-ness) and Bartholomew’s emphasis on efficient organization while broadening the scope to include hoop houses (poly tunnels), canning and preserving, even cooking. It is truly a one-stop-guide to provide yourself all the vegetables you’ll ever need, year-round.

Richards is the only author on this list I discovered on YouTube, having watched his channel for years. His home in Wales has a more temperate climate than mine, and the book would be far less valuable if Richards didn’t stick to growing recommendations “roughly corresponding to USDA Hardiness Zone 5,” which describes Elizabethtown’s. I’ve only recently bought the book and have yet to test how closely I can follow its month-to-month guidance, but the garden maps, sowing schedules, use of hoop beds, hot beds, and poly tunnels for maximal yield is very appealing. Whether you’re looking for pure self-sufficiency or to market your yield, “The Self-Sufficiency Garden” is a treasure.

For those looking to market, few books are as widely known and praised as Canadian Jean-Martin Fortier’s “The Market Gardener” (New Society, 2014). While written more than a decade ago, the book has been updated as recently as 2022. This is important because one of the first things Fortier does is lay out the basic costs to get started market gardening. He also shares the glories: “For the last ten years, my wife and I have had no other income than the one we obtain from our 1 1/2-acre micro-farm.” The book covers all the necessary growing techniques and pest control methods (there’s a chapter on deer!) but also how to sell, where to sell, what works best.

Even if you don’t want to market garden, Eliot Coleman’s “The Winter Harvest Handbook” (Cheslea Green, 2009) is a masterclass in the practice of gardening itself, with one huge bonus: a focus on growing through the winter in both heated and unheated greenhouses.

This is the most-read and referenced book in my collection. Dog-eared and covered in margin notes, I’ve used this full-color, candidly written guide as my go-to for recent tomato production as well as production in my two hoop houses. Coleman introduced me to cold-hardy, leafy greens I’d never heard of before, as well as taught me the concept of in-ground storage for crops such as carrots, beets, and leeks. Of all the books, I’ve found this one feels most suited to the Elizabethtown climate, and that’s probably owed to Coleman’s vegetable farm being in Maine, on the 45th Parallel, same as here.

Happy reading and good luck gardening!

Comments are closed.