Though its history tends not to be as fixated upon, Willett Distillery shares a remarkably similar narrative arc with the hallowed Stitzel-Weller, from its founding shortly after Prohibition to halting production in the 1970s during the Whiskey Glut era. Nurtured through the 1980s wilderness and into the eventual bourbon boom by Even Kulsveen, who married into the Willett family, the Bardstown, Kentucky, distillery is now guided by the next generation, namely president and “chief whiskey officer” Britt Kulsveen and her brother, master distiller Drew Kulsveen.

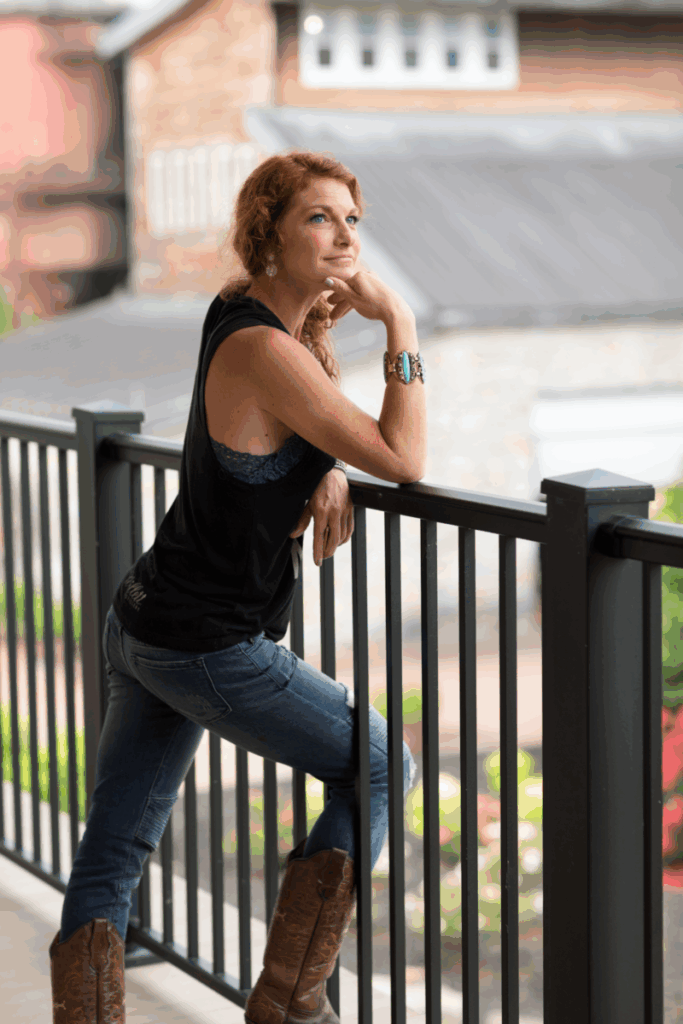

In an industry already known for idiosyncrasy, Willett has earned a nonconformist reputation on its path to a cult-like following among whiskey lovers, as demonstrated by retro label designs that never saw a focus group and a numbering scheme on bottles of its highly coveted Family Estate Single Barrel Bourbon so byzantine that committed collectors resort to spreadsheets to impose order. Britt Kulsveen has some thoughts on Willett’s unusual approach, as well as being the rare woman to lead a major Kentucky distillery.

[Editor’s note: Even Kulsveen, a Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame inductee, passed away in September, shortly after this interview was conducted.]

Growing up in Bardstown in the 1980s, what was your awareness of the status of the distillery and the overall bourbon industry?

None, really. We all have our own normalcy, right? I was five years old when our father took over in 1984, and my normalcy was the smell of machine oil in the bottling house. I had no knowledge outside our little bourbon bubble. Here’s an example: My grandmother made yeast rolls at Thanksgiving, and one of my jobs was to drizzle them with a slurry of Old Bardstown [a Willett bourbon brand] and powdered sugar. That seemed perfectly normal to me.

I’ve heard that the liquor you snuck out of the house for parties differed a bit from most highschoolers.

I think a lot of teenagers in Kentucky had access to whiskey, but I don’t think they had access to the same kind of spirits cabinet as at our house. There were unmarked bottles in every size from way back. I was sneaking twenty-year-old bourbon and mixing it with lemonade. And when I started at LSU in 1997, my classmates there didn’t know about our distillery, or really bourbon in general. The only bourbon at bars then that people recognized as having an elevated status was Maker’s Mark.

Was there a particular moment when you realized you wanted to be involved in the family business?

Right before Hurricane Katrina moved me back to Kentucky, I was living in Baton Rouge and mulling starting a distributorship there to be on that side of things. At that time, Drew had just joined the business, and otherwise it was just our dad and a few others. I had no intention of getting involved, never thought about wanting to be a part of the family business. But when I returned to Bardstown to help on the bottling line, there were multiple stacks of papers on top of filing cabinets in the office, and I was like, Oh my God, it’s going to take a lifetime to get this organized. My dad is an intimidating Norwegian. Normally I was terrified by him, but soon he was terrified by me.

From there, you were named Willett president in 2018, but your other title, chief whiskey officer, might be even better.

My favorite game with my best friend, my wingwoman, is wordsmithing, and she came up with chief whiskey officer. It’s great, but titles here are a shortcut that don’t really define our identities. This is a family operation, and I’m truly coleading this with my brother.

Do you find it difficult not to talk business at family gatherings?

Oh, we talk business all the time. There’s definitely a blurred line where those parts of our lives are always blending together. The thing is, we’re getting to live where our passion meets our purpose, so it’s not really work for us.

Women are making great strides in the industry, but it’s still rare for a woman to be at the top of a major Kentucky distillery. Are there times when you feel aware of that?

Sometimes. It wasn’t too long ago that when you saw women in the whiskey business, they were the beautiful women hired to pour at events. I had experiences where men who came up to our table would ask questions of anyone but me. As far as being president, I don’t think too much about it—I’m just a leader of our people, doing what needs to be done.

Most of the time you’re doing it while clad in boots. How did that become your trademark attire?

I have my own style and can’t explain it. Boots are pretty practical here for walking through tall grass on the way to the warehouses. At this point, my boots aren’t a fashion statement—they’re an extension of my legs.

From throwback packaging to somewhat mysterious distribution, Willett doesn’t seem to chase the same trends as other major distilleries. Do you agree?

It’s my passion to speak to this. It comes down to being independently family run. We have the rare gift of freedom and autonomy—not a lot of companies operate on our level and get to do that. Frankly, we’re more interested in what we’re doing than what others are doing. Being independent also means we get to go rogue sometimes. We don’t do things like anybody else does.

What was your reaction when bottlings of Willett Family Estate became so coveted by bourbon collectors?

My perception of time is deplorable. What I can tell you is that we developed a cult following over a couple of years. Before that, though, we went into liquor stores and waited for two hours for a meeting. We have the utmost gratitude for the people who believed in us and what we were making. Now it can be frustrating to find a bottle of Family Estate, but that’s not a bad problem to have on this side of the business. There may be some excessive luxury in our whiskey, but we’re more than Family Estate. I love that our other expressions, from Old Bardstown to Kentucky Vintage to Noah’s Mill, each have their own distinct personalities. Some are in the same wine- or cognac-style bottles that my father used because that’s what he had, and he drew the labels we still use today. So many people have no idea that those come from our house, too.

Bourbon tourism is huge right now. How does the concept of Southern hospitality translate to the visitor experience at Willett?

As much as Willett is now a destination, I can tell you one thing that remains unchanged—we are intentionally intimate. Our Bar at Willett has capacity for eighty people, but we seat only forty. I always say that we’re in the business of hospitality, and that’s about being present and engaged and serving everyone like a guest in our home. That’s how we’ve been raised.

Steve Russell is a Garden & Gun contributing editor who also has written for Men’s Journal, Life, Rolling Stone, and Playboy. Born in Mississippi and raised in Tennessee, he resided in New Orleans and New York City before settling down in Charlottesville, Virginia, because it’s far enough south that biscuits are an expected component of a good breakfast.

Comments are closed.