They sit beneath oak branches and atop gurgling fountains. They seemingly sprout from lush vignettes of flowers and creeping vines, these more than three thousand sculptures that inhabit Brookgreen Gardens, near Murrells Inlet, South Carolina. Each time I’ve visited this sprawling nine-thousand-plus-acre Hammock Coast landmark, about two hours away from my home in Charleston, I’ve walked around shaggy azalea bends to find surprising artworks, and past plenty of striking bronze statues, but for some reason I return again and again to Alligator Bender. All cool white stone and curves, the carved piece hovers above a pool of water, the namesake reptile curling from snout to tail into a seat for a man with the firmest, roundest Italian-marble butt.

Perhaps it’s rude to stare, but I can’t help but study this sculpture near the back of the gardens, watching the way the seasons unfold around it. Lily pads float in the pond beneath the alligator before spiky purple water lily blooms emerge in the summer. Come winter, along the path framing the spot, camellia buds open into pink-and-white fireworks. And always, moss and ferns trace the brickwork, water dribbling lazily over the pond’s edge.

Photo: Gately Williams

Dionysus by Edward McCartan, with a cheeky peek at Alligator Bender by Nathaniel Choate.

On my most recent visit this past fall, beside Alligator Bender and nearly everywhere else, workers balanced on ladders and wrapped tiny lights around tree trunks and branches, preparing for Nights of a Thousand Candles. The public garden’s wildly ambitious and dearly beloved holiday celebration runs from the end of November through early January. “That is the one event that every staff member and volunteer works on or is involved in somehow, either setting up or manning it,” Robin R. Salmon tells me when I chat with her during my visit. She’s both a vice president and the curator of sculpture here, and this January, she’s excited to help inaugurate the garden’s years-in-the-making new welcome center and conservatory.

Photo: Gately Williams

An egret with a snack.

Winter, Salmon says, has always been one of her favorite seasons over the fifty years she’s worked at Brookgreen—and not just because of the cooler air and the glow of all those candles. “You get the darker greens, and the grass goes golden and brown,” she says. “It’s important in the cycle of nature to see brown sometimes, to have some of the plants fade back a bit. And that’s really the best time to see the sculptures.”

Photo: Gately Williams

The sculpture Indian and Eagle by C. Paul Jennewein in Brookgreen’s Spanish moss–shaded arboretum. In fall and winter, Brookgreen’s staff hang lights for the annual Nights of a Thousand Candles.

That mild winter weather also drew the Huntingtons—the couple who founded Brookgreen in 1931—to South Carolina in the first place. Anna Hyatt was already an established sculptor when Archer Huntington, a scholar of Spanish history and art, commissioned her to create a medal for the Hispanic Society of America in 1921. They wed two years later, on what happened to be both of their birthdays—March 10. After she contracted tuberculosis a few years into their marriage, the couple purchased four large former rice plantations along this stretch of Carolina coast, where Anna could rest in the winter and continue to sculpt.

Photo: Gately Williams

One of the figures in Circle of Life by Tuck Langland.

Inspired by Archer’s love of Spain, they built Atalaya, a Moorish castle centered around a stately tower at what is now Huntington Beach State Park, which sits just across Highway 17 from Brookgreen. I recently walked through the castle for the first time (don’t wait as I did—visit Atalaya the same weekend you visit the gardens to see how the two reflect each other) and soaked in the couple’s shared vision of a creative life: the indoor and outdoor studios where Anna worked; the large animal pens where she observed alligators, swans, and even a bear for her sculptures; his office lined with bookshelves; and the exterior’s scrolling ironwork with hand-shaped floral details.

Photo: Gately Williams

A view toward Atalaya Castle, the former home of the couple who built Brookgreen Gardens, at what is now Huntington Beach State Park.

From their bedroom, the couple could see the Atlantic, and a partially shaded walk from the castle leads straight to the beach. On my visit, right as I crested the final dune—and as if the tourism board had tipped them off beforehand—a pod of three or four dolphins arced out of the sparkling water. It’s no wonder this landscape became the Huntingtons’ refuge. “They soon began to collect sculpture specifically for the gardens,” Salmon says, adding that this was during the Depression, a time when many artists especially appreciated the support. “Archer was the philanthropist who had the vision to establish a place like Brookgreen, but it was Anna, with an annual allowance they agreed on, who bought art and made this happen. She became a true patron.” The assemblage would grow to become the Huntingtons’ legacy in stone—Brookgreen now holds the country’s largest and most comprehensive collection of American figurative sculpture.

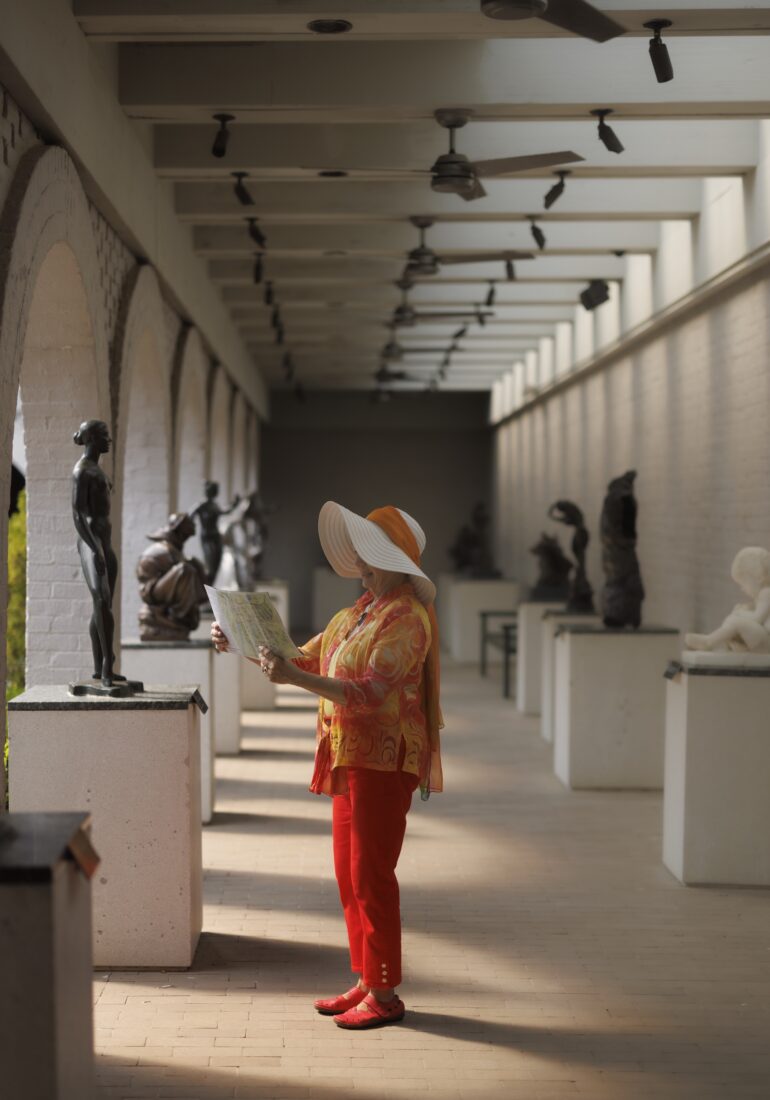

Photo: Gately Williams

The Brown Sculpture Court at Brookgreen Gardens.

Over the generations, the plantings have matured and expanded, and the artwork has seemingly multiplied. Brookgreen added nature trails in the 1950s, and an impressive conservation-focused zoo in 2000. In the decade I’ve reported on Southern gardens, I’ve spoken to several artists and naturalists who cite Brookgreen as a touchpoint in their lives. I recently asked Celeste Albers, a farmer on South Carolina’s Wadmalaw Island, about her regular visits, starting when she was a young girl. “There’s this part of the garden I always like to walk,” she explained, “where you have the sculptures and this manicured formal space on one side, but then you look out and it’s this raw natural beauty on the other.” She was describing a spot near the edge of a terrace with a viewpoint toward the Waccamaw River. Of course it’s exciting to travel someplace new, but there’s also something important about returning to places you already feel connected to—to witness both their small shifts through the seasons and the big ways they—and perhaps you—evolve through the years.

Photo: Gately Williams

Water lilies.

This last trip, I soaked up the shade in Brookgreen’s leafy arboretum and the scented roses that fill the Poetry Garden with fragrance and color. When I took a break on a bench near my pal Alligator Bender, I pulled up the map feature in my phone’s photo gallery. I scrolled down to the very first picture I took at Brookgreen—a peacock sculpture near the entrance. The date was April 11, a decade ago. I didn’t know him then, but in Chicago on that exact day, someone named Max was celebrating his birthday. I thumbed through more photos: native pitcher plants in the spring, bright purple beautyberries another summer, an adorable goat sculpture, an actual live goat at the zoo.

Photo: Gately Williams

A Gulf fritillary butterfly atop zinnias at the gardens.

Then came rows and rows of photos on my own birthday, May 11, in those early months of the pandemic, when I played hooky from work and drove to Brookgreen solo. I was thrilled to get out of my apartment, taking way too many pictures of plants and then rambling out toward the river, where there’s a low, manicured labyrinth meant for meditation. I don’t remember being too sentimental about it, but I do recall walking the curving lines, thinking about an argument I’d had with a guy I was sort of dating—about how we never went for walks together. I asked God while doing little loopy-loos in the maze, hey, I’m not getting any younger here—would it be too much to ask to fall in love with someone who would just go on a walk with me? Wasn’t there some man, somewhere, preferably with a job and under the age of forty, who respected both me and nature, at least a little bit?

The next pictures were from that summer—exploring Brookgreen at night with friends, twirling under Spanish moss lit by string lights. And then there was May 2024, a surprise gift of a return birthday trip to the gardens. I zoomed in on one picture of a massive magnolia blossom, my hand extended for scale. There are rings on my finger because I’d been married a few months by then, to Max—a florist who moved from Chicago to Charleston during the early days of the pandemic and who has more curiosity about flowers than even I do. Among the many pictures of him walking under trees and beside the sculptures, there’s a video I took of us studying how water trickles over the ferny brick ledge of the Alligator Bender—a template for the tiny fishpond we were building in our garden back home.

CJ Lotz Diego is Garden & Gun’s senior editor. A staffer since 2013, she wrote G&G’s bestselling Bless Your Heart trivia game, edits the Due South travel section, and covers gardens, books, and art. Originally from Eureka, Missouri, she graduated from Indiana University and now lives in Charleston, South Carolina, where she tends a downtown pocket garden with her florist husband, Max.

Comments are closed.