A study reviews the evidence and proposes that the first modern humans who colonized the world departed from a coastal ‘Garden of Eden’ in the South Cape, rapidly migrating along the shoreline toward the Horn of Africa and beyond.

Where do we come from? It is one of humanity’s oldest questions. For decades, the dominant narrative has placed the great exodus of modern humans—the journey that led us to colonize every continent except Antarctica—from East Africa. However, a scientific review published in 2025 in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa challenges this perspective and presents a compelling case for a different starting point: the southern tip of the African continent.

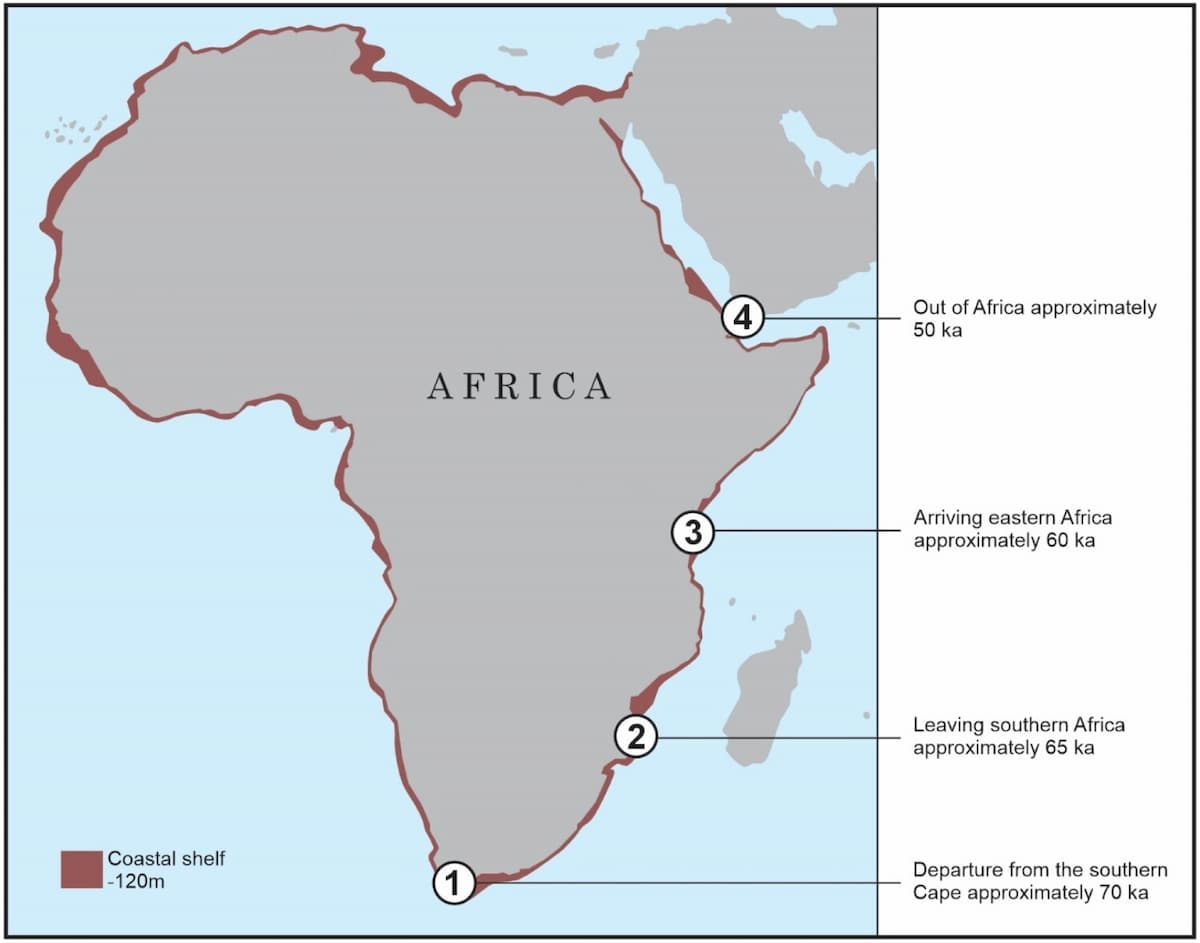

The paper argues that a group or groups of anatomically modern humans, culturally and technologically advanced, departed from the southern Cape region around 70,000 years ago, embarking on a coastal journey that would take them out of Africa between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The authors, led by Alan Whitfield of the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, propose that this southern coast was a true Garden of Eden that not only sustained these populations but also provided them with the tools and adaptations needed to embark on humanity’s greatest adventure.

Map showing some of the southern African rock caves and shelters occupied by hominins in the past and mentioned in this review. The location of the main section of the relic Palaeo-Agulhas Plain in the southern Cape, now under 130 m of water, is also shown. Credit: A. Whitfield et al. 2025

Map showing some of the southern African rock caves and shelters occupied by hominins in the past and mentioned in this review. The location of the main section of the relic Palaeo-Agulhas Plain in the southern Cape, now under 130 m of water, is also shown. Credit: A. Whitfield et al. 2025

The Garden of Eden of the South Cape

Imagine a place with a mild climate, moderated by the ocean, where food was abundant and varied throughout the year. This is how researchers describe the southern Cape coast during the Late Pleistocene. This region, stretching from Cape Agulhas to Cape St. Francis, was a paradise for hunter-gatherers.

The diversity and abundance of edible roots, bulbs, tubers, and corms could be interpreted as a ‘coastal cornucopia’, the study notes, citing previous work. But the real supermarket was on the shore. The inhabitants of this coast began exploiting marine resources, such as shellfish and fish, at least 160,000 years ago. This diet, rich in protein and, crucially, in long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, may have been a key factor in the cognitive development of these humans.

Fish and shellfish are an excellent source of protein, and the long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids that promote brain development in fetuses of pregnant women and in growing children may have enhanced cognitive ability in the evolution of a more “modern” hominid society of the Stone Age in the Cape, the authors explain.

The Key: Adaptation to Coastal Life

What made these humans of the South Cape unique was not just what they ate, but how they accessed their food. They developed a sophisticated coastal culture. They learned to read the lunar cycles to predict the spring low tides, the ideal moments to gather shellfish from intertidal pools. This understanding of the marine environment was, according to the Coastal Hypothesis, a fundamental preadaptation for their future migration.

Life on the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain of the southern Cape during the Last Glacial Period that reached a peak approximately 20 ka showing the utilisation of both marine intertidal shellfish (foreground) and terrestrial mammals (background). The woman in the bottom left of the painting is applying red ochre paste to the cheek of the young lady seated before her. Credit: Maggie Newman

Life on the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain of the southern Cape during the Last Glacial Period that reached a peak approximately 20 ka showing the utilisation of both marine intertidal shellfish (foreground) and terrestrial mammals (background). The woman in the bottom left of the painting is applying red ochre paste to the cheek of the young lady seated before her. Credit: Maggie Newman

The archaeological evidence from caves such as Blombos, Pinnacle Point, and Klasies River is overwhelming. In these sites, researchers have found:

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

Specialized bone tools, possibly used for projectile hunting or sewing clothing, dating back 100,000 years.

Use and processing of ochre (a red pigment) from as early as 162,000 years ago, including an ochre-processing workshop in Blombos Cave from 100,000 years ago. Ochre is associated with symbolic behavior such as art and body decoration.

Abstract engravings on pieces of ochre and bone, and the oldest known drawing made with an ochre crayon, dated to 73,000 years ago.

Advanced lithic technology, including the thermal treatment of stones to make better tools and the production of microliths (small stone blades) for complex weapons such as bows and arrows from 71,000 years ago.

Jewelry, in the form of perforated shells used as necklaces and earrings.

Taken together, the Late Pleistocene MSA [Middle Stone Age] findings demonstrate that the inhabitants of the Cape coast at that time exhibited a range of culturally and cognitively complex behaviors, the paper concludes.

Why Leave Paradise?

If life was so good in the Garden of Eden, what drove a group to embark on a journey into the unknown? The researchers propose a combination of factors.

Around 70,000 years ago, the climate in the region began to become colder and drier. This may have reduced freshwater resources and the productivity of terrestrial plants and animals. At the same time, growing human populations may have increased competition for the most prized coastal resources and for ideal cave shelters.

It is likely that growing pressure from competing, successful, and expanding bands of H. sapiens, possibly combined with paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental changes, provided the trigger for an initial migration eastward and then northeastward, the authors suggest.

Map of Africa showing the possible coastal route taken by modern humans together with a hypothetical timeline for the journey. The area shaded in black represents the shelf area that would have been exposed during glacial maxima of −120 m MSL (modified after Compton, Citation2011). The exposed shelf area during the out of Africa migration would have been between about −50 m and −100 m below the current MSL. Credit: A. Whitfield et al. 2025

Map of Africa showing the possible coastal route taken by modern humans together with a hypothetical timeline for the journey. The area shaded in black represents the shelf area that would have been exposed during glacial maxima of −120 m MSL (modified after Compton, Citation2011). The exposed shelf area during the out of Africa migration would have been between about −50 m and −100 m below the current MSL. Credit: A. Whitfield et al. 2025

There are even signs of crisis moments. At the Klasies River site, the presence of human bones in food waste deposits has led to speculation about episodes of cannibalism, possibly caused by food shortages.

The Route Out: The Coastal Highway

The Coastal Hypothesis not only changes the starting point but also the route. The researchers argue that migration northward along Africa’s east coast was more viable than any inland route. Why?

The coast offered a steady and predictable supply of shellfish, easy to collect for an already expert population. Abundant intertidal shellfish, particularly marine mollusks, are always available and relatively easy to harvest, the study notes. Freshwater sources, such as rivers, streams, and springs, are generally more prevalent along a coast than inland.

Traveling along the coast was also less demanding than crossing mountain ranges, deserts, or large lakes. The mostly level topography facilitated movement. Dangerous encounters with large predators such as lions or crocodiles were less likely on open beaches than in inland savannas or forests.

There is no evidence of an equivalent and contemporaneous MSA culture on Africa’s east coast. This suggests that the migrants from the South Cape did not encounter established coastal populations to compete with, possibly due to the negative impact of the Mount Toba supereruption (74,000 years ago) on human populations in tropical Africa.

The Great Crossing: From Africa to Arabia

The critical point of the migration was the crossing from the Horn of Africa to the Arabian Peninsula. Between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago, sea levels were much lower due to northern hemisphere glaciations. The Bab-al-Mandab Strait, which today separates Djibouti from Yemen, was significantly narrower and shallower.

The sea level in the region was ~100 m below the present as early as 65,000 years ago, the review states. The researchers propose that much of the seabed was exposed, and that the remaining central channel of water was less than 4 km wide. A crossing on primitive rafts was a “possible option,” a skill these humans would later demonstrate upon reaching Australia.

This theory directly challenges the more widely accepted models, which often depict the origin of migration in East Africa without considering a southern contribution. The authors acknowledge that current genetic evidence is complex and does not clearly point to a southern origin, but they argue that the explosion of cultural and technological complexity appears first and most clearly in southern Africa.

There is no equivalent evidence from East Africa, particularly in terms of the use of intertidal marine food resources, which we now know was an important factor in facilitating the human colonization of the world, they state firmly.

The Coastal Hypothesis paints a fascinating picture of our ancestors: not merely hunters of the savanna, but ingenious coastal foragers who mastered their marine environment. Their story is that of a population that, from a privileged refuge at Africa’s southern tip, developed the tools, culture, and resilience needed to venture beyond the horizon.

If future research—especially that exploring the now-submerged continental shelves where much of this journey took place—confirms this theory, our understanding of the “great journey out of Africa” could change forever, relocating the starting point of global humanity to the ocean-washed shores of what is now South Africa.

SOURCES

Whitfield, A., Helm, C., Rust, R., Stear, W., & Thackeray, F. (2025). The Coastal Hypothesis: one possible migration route for Late Pleistocene Homo sapiens from the southern tip of Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa, 1–23. doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2025.2545798

Comments are closed.