Sun Valley was the inspiration in BYLA’s plan to bring the area’s mountain ecology to Ketchum’s downtown.

By Timothy A. Schuler

In the 1930s, a publicist working for a resort developer nicknamed Idaho’s Wood River basin “Sun Valley” and coined the tagline “Winter sports under a summer sun.” At 5,750 feet above sea level, the alpine valley is surrounded by five distinct mountain ranges and receives about 250 days of sunshine a year. That sunlight makes for a pleasant day of downhill skiing, but in the summer, when the sun doesn’t set until well after 9:00 p.m., it sends visitors looking for a spot of shade.

“Here in Ketchum, the sun is so intense,” says Chase Gouley, ASLA, a principal and owner at BYLA Landscape Architects, which is based in Ketchum, Idaho, but also has an office in Bozeman, Montana. For a recent outdoor space that BYLA designed in Ketchum’s downtown, the valley’s namesake became something of a productive adversary.

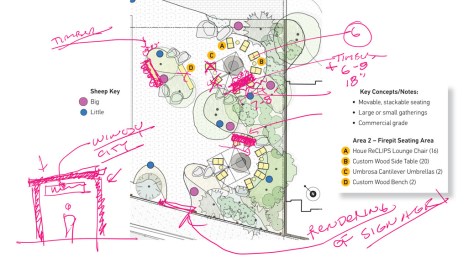

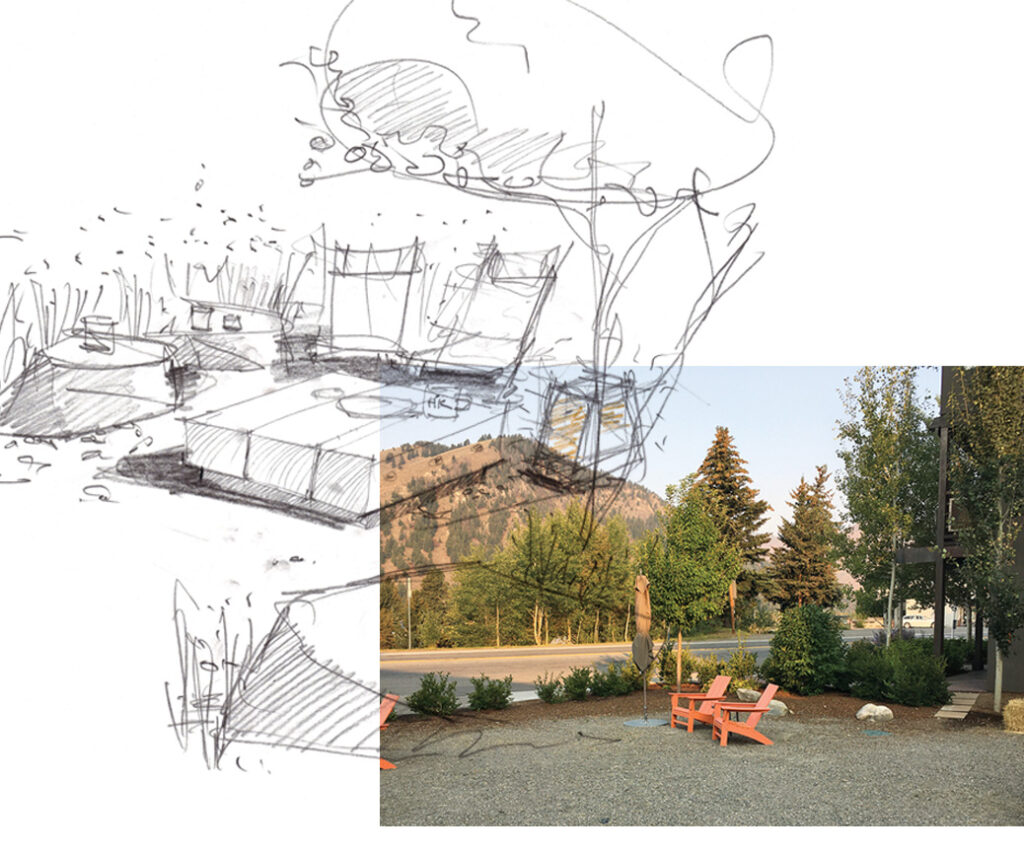

An early sketch captures the “campsite” feel BYLA wanted to create. The original space faced a busy highway and lacked any spatial definition or shade. Images by BYLA Landscape Architects.

An early sketch captures the “campsite” feel BYLA wanted to create. The original space faced a busy highway and lacked any spatial definition or shade. Images by BYLA Landscape Architects.

Between two wings of the recently renovated Hotel Ketchum is a 4,000-square-foot sliver of land forming a courtyard, hemmed in on three sides by the hotel and on the fourth by a state highway. The hotel had tried to activate the space with groupings of picnic tables and orange Adirondack chairs, but the project area faced west, and the ground was an expanse of dark, heat-absorbing gravel. “You’ve got these amazing views out to Warm Springs [and Bald Mountain], but in the afternoon and evening, that’s exactly where the sun is, so it’s just beating on you,” Gouley says.

The orientation presented another challenge: The prime views were toward the busy frontage of Highway 75, an active thoroughfare that serves as the gateway to the Sawtooth Mountains. Whatever screening strategy the designers chose, it couldn’t be so tall or opaque that it blocked the mountain views. At the same time, the edge along the sidewalk needed to function as a public entry point, which the client—HayMax Hotels based in Aspen, Colorado—hoped would welcome more foot traffic in addition to hotel guests, so any redesign couldn’t turn its back to the street. “How do you create a space that’s right on Highway 75 that doesn’t feel like you’re sitting along the highway?” Gouley asks.

Adopting the materials and visual language of high-mountain pastures and sheep corrals came gradually. Image by BYLA Landscape Architects.

Adopting the materials and visual language of high-mountain pastures and sheep corrals came gradually. Image by BYLA Landscape Architects.

The project became an experiment in how to cost-effectively bring nature into a tight, urban space. The goal was to create both a microclimate that could mitigate excessive heat and noise and a cultural touchstone that would resonate with locals and visitors alike. The answers came gradually from multiple directions. What they had in common was the rich history of Sun Valley’s landscapes, particularly the high-mountain pastures that, in the mid-1800s, became the domain of transplanted Basque sheepherders. “I’m born and raised here in Ketchum and spend a lot of time out in the woods, and throughout [the valley] there are sheep corrals that are either currently being used or that are left over from a time when it was more rural,” Gouley says.

The landscape architects proposed a design that blended the feeling of Idaho’s high-mountain meadows with the experience of backcountry camping, along with a sense of play that drew on the bold, graphic identity of the hotel’s brand. Specifically, sheep. Since the mid-1990s, Ketchum has hosted the annual Trailing of the Sheep Festival, a four-day event featuring the foods and music of the various sheepherding cultures that call the region home. The sheep themselves are the main event, with thousands of animals driven through downtown each October, making their way from their mountain pastures to grazing lands in the valley.

“This might be the only nature [visitors]

connect with. That’s why we’re trying to get

a little bit of Idaho in there.”

—Ben Young, ASLA

HayMax Hotels embraced this feature of the local culture in its design for Hotel Ketchum, with sheep-themed art and murals throughout the property. Inspired by this theme, BYLA called its concept for the outdoor space the Pasture. Shady nooks would provide places for small groups to gather, while large boulders would encourage climbing and double as extra seating. “If [you] went out to one of these sheep corrals right now, what would you see? You’d see aspen, you’d see native grasses, you’d see rocks, you’d see some wildflowers,” Gouley says. “We took that and brought it back.”

Ben Young, ASLA, BYLA’s other principal and owner, says that the idea with the Pasture was to “channel the spirit of the hike—John Muir, wilderness, all those things—and bring it a little bit closer into town.” There were practical considerations driving the concept as well. Pockets of Populus tremuloides and Amelanchier canadensis could provide shade and filtered sunlight without the hard edge of an umbrella or shade sail. “Umbrellas obstruct views because they create a canopy that’s only so high, and then all of a sudden you can’t see out,” Gouley says. With a tree, he says, “you get the height, and you get this filtered view, and they create a different microclimate.” Trees are also the lower-maintenance option, Gouley explains. “They’re going to continue to grow, right? An umbrella is going to wear out, tip over, break.” Still, the trees aren’t yet enough on their own, so the designers did specify a tall, angled umbrella they had used on other projects for the main seating areas. Similarly, seating made from salvaged wood—fabricated by Gouley’s father, a frequent collaborator of the firm’s—is ultra-durable but inexpensive, an ever-present consideration for a small hospitality project like the Pasture.

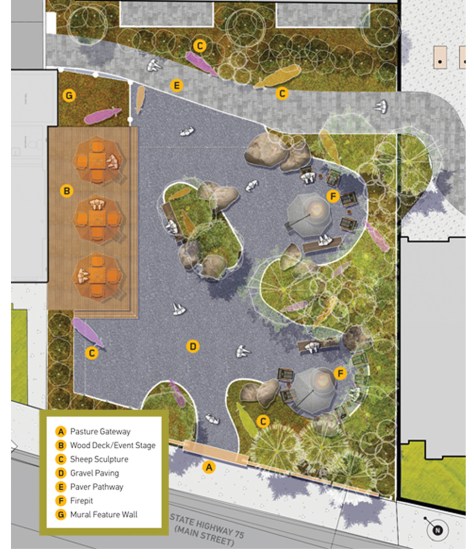

The final plan simplifies the layout and enlarges the seating areas, sizing them for multiple groups. Image by BYLA Landscape Architects.

The final plan simplifies the layout and enlarges the seating areas, sizing them for multiple groups. Image by BYLA Landscape Architects.

If the material palette came somewhat quickly, the layout and street frontage took more time to resolve. Initially, the designers envisioned as many as seven distinct seating nooks. When the hotel group requested that each nook have a firepit, they knew the number would have to shrink. “We were loving this idea of all these little nooks,” Young says. But with firepits, “[you] need a lot more room because some people like to be up close to the fire, and some people like to push their chair back.”

To figure out exactly how much space the firepits would need, and therefore how many nooks they could realistically provide, the designers spent extra time on-site. “This is literally half a mile from our office,” Young says. “I can bike there in two minutes.” The team used paint to draw out the planting beds, the firepits, and the furniture, tweaking dimensions as needed. It’s a tactic BYLA uses on most of its projects, Young says. “You can only plan diagram stuff so much,” he says. At some point, you have to “stage it in real life.” Once each element is set, the landscape architects use a drone to capture aerial images of the layout.

Limited materials and bright colors enliven the space, including the seating area for an ice cream shop. Photo by Halsey Pierce.

Limited materials and bright colors enliven the space, including the seating area for an ice cream shop. Photo by Halsey Pierce.

At the site, what they found was that, with the firepits added, the space could comfortably accommodate just two seating nooks, in part because as a seating area grows, it needs to be big enough to feel usable by multiple parties. “You have to make it big enough so that if one person is sitting there, someone else [can] use the space too,” Young says. The main seating areas were relocated to the south side of the site, where the trees and shrubs double as a privacy screen for hotel guests, leaving the northern half of the site, where a wooden deck holds café tables for a small retail space—currently occupied by an ice cream shop—more open. Along the western edge, where the site meets Highway 75, the team created a border of aspen, lodgepole pine, and fountain reed grass, with a central opening to direct foot traffic.

As the design evolved, so did the particularity of the pasture concept. The client proposed a second sheep mural to enliven the wall above the retail space, as well as a series of life-size sheep sculptures, painted in a mix of pastel hues, that would be scattered throughout the space. It was the former Hotel Ketchum general manager Jeff Bay who suggested what has become the Pasture’s most iconic element: a corral-style fence and gate along the sidewalk. “That helped create that sense of place even more,” Gouley says. The landscape architects might have avoided the idea because of the potential for it to devolve into full-blown kitsch, but instead they chose to lean in, designing a traditional hanging sign and a series of colorful metal sheep figures—including one that’s black—for the top of the gate. “There are little hints of humor throughout,” Gouley says of the project.

Islands of trees and boulders and a more choreographed environment invite the public in. Photo by Halsey Pierce.

Islands of trees and boulders and a more choreographed environment invite the public in. Photo by Halsey Pierce.

Opened in July 2023, the Pasture is a mix of playful artifice and rugged naturalism. It succeeds in bringing a slice of the region’s native ecology into the city and marrying it with an agrarian authenticity. Most importantly, it invites gathering in a shaded space while preserving a visual connection to the mountains beyond. While Young hopes the aspens and boulders spark a feeling of recognition for locals, the visitor he had in mind as they designed the space is the one who comes to Ketchum for work or a wedding, who may not get to experience the forests and mountains firsthand. “This might be the only nature they connect with,” he says. “That’s why we’re trying to get a little bit of Idaho in there.”

Timothy A. Schuler is a design critic, journalist, and contributing

editor at LAM.

Feature photo by Halsey Pierce.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Comments are closed.