Before he became a James Beard Award–winning chef and television host, Andrew Zimmern grew up in East Hampton, Long Island, where he woke in the wee hours of the morning to watch local fishermen push massive rowboats out to sea and haul in nets overflowing with fish. While those practices have largely faded from the country’s collective consciousness, his love of seafood has not.

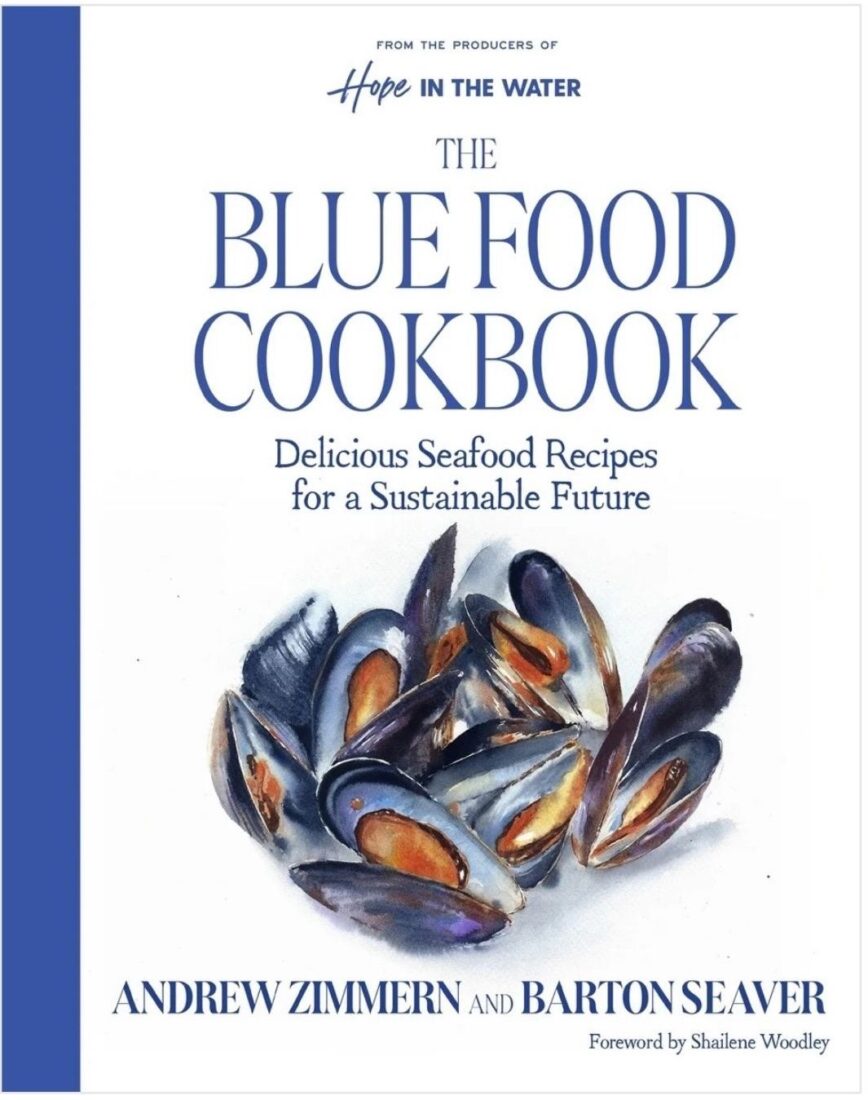

In The Blue Food Cookbook, co-written with Barton Seaver in collaboration with ocean food advocacy nonprofit Fed by Blue, Zimmern highlights how feasible sustainable consumption really is. Along with innovative recipes, the book offers tips on how to purchase, cook, and consume all kinds of “blue food”—that is, any food harvested from the water, including seaweed.

Zimmern chatted with G&G about his path to making the cookbook and why Americans should be eating more seaweed and steaming more fish. Read that interview below, and preview his recipes for fritto misto, oysters vadouvan, and butter-basted scallops.

Photo: Eric Wolfinger

Seaver and Zimmern get their feet wet at Hog Island Oyster Farm.

What inspired the cookbook?

I grew up on the water in East Hampton. And I spent summers, holidays, weekends, every chance my family could get out at the beach. We ate a lot of fish and shellfish. We didn’t call it foraging, but I went clamming with my dad. We went crabbing in Georgica Pond. We pulled mussels out of the rocks on the jetties at Main Beach and Georgica Beach near our house. My mom would wake me early to watch people push these giant rowboats out through the waves, with six or seven people on oars and giant nets mounted in the middle. At dawn, they would pull in the net they had set out the night before, and then we would go late morning or early afternoon and see the fish that was pulled out of the water in the case.

I asked my mother why she was showing me this, and she said, “Because in a couple of years, it’ll be gone.” And this was 1965, ’66. And she was right, it disappeared. Flash forward almost sixty years: This cookbook project is designed to remind people that we can work and feed ourselves out of our oceans while protecting them at the same time.

Ways of life come and go. People don’t set out to sea in long boats with nets quite the way they used to. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be learning lessons from those people about what we should be eating: smaller fish taken close to shore; ones that aren’t threatened; losing our dependence on tuna, salmon, halibut, cod, and shrimp, for God’s sake; and exploring what would make for a delicious, sustainable future.

An example of this is aquaculture, which is nothing new. People have been using aquaculture for thousands of years as a way to sustain themselves. For the most part, we have now figured out feed systems, net systems, fish per cubic yard issues, fish pollutants. Aquaculture used to be a really dirty word to me, but now the product is great. I would put a Riverence trout up against any trout, wild or farmed, in terms of flavor.

You write that the cookbook is “a narrative about why seafood matters, how it has sustained cultures for millennia, and why we need to protect and enhance it for generations to come.” What do you hope readers and chefs will take away from this book?

I would like everyone to eat one more seafood meal a week. I would like them to understand what being a sustainable cook and eater means, but you have to be educated. You have to understand that it’s not okay to buy seafood from a place that can’t tell you where their seafood comes from. We don’t need to buy a giant piece of halibut or salmon every time we go to the seafood market. They’re delicious, but we need to diversify our dining choices in America. There are so many delicious small fish that are underexposed in our world today, and we highlight a lot of them in this book.

We talk a lot about seaweed in this book. By 2025 there will be more seaweed harvested in America than potatoes. The majority of that is exported overseas. Why aren’t we eating it? It’s some of the most nutritious and delicious food that I know of, and it’s eaten and accepted in almost every food culture around the world other than ours.

When you take a handful of dried wakame or kelp and rehydrate it and mix it half and half in a stir fry or a salad, you’re doing the same thing that eating a few small mackerel or porgy does, which is—one plate at a time—decreasing the demand for a caged chicken meal or a confinement lot pork or beef meal. I believe in big food. I mean, we have billions of people on this planet. I hope we have some big food solutions, but it has to be done the right way.

This book is about entertaining and educating the consumer. This is not a weighty tome that is thumping its hand on a table telling people what to do. Quite the contrary—we have two authors who disagree on a lot of things. Those are my favorite parts of the book. There’s more than one way to cook crab cake. But one of the things I really love about this book is that it’s fun and entertaining to read. It has 140 recipes that are absolutely delicious and that are going to work for everyone.

Were there any moments where a recipe really evolved or surprised you?

All the time. [Like] my recipe for fish collars. Are we gonna do tuna? That’s a big, giant honking collar if it comes from a big fish. What are the collars that most people have access to? Is it going to be fresh or frozen? How are we going to prepare these delicious beauties? We wound up with two different fire-kissed options over the grill that obviously someone can do in a sauté pan or under the broiler.

We wanted to do mussel and clam dishes in the book. We thought, “Does the world need another linguini and clam sauce recipe?” We thought yes. Do they need another moules marinière or mussels fra diavolo recipe? We thought so, because we thought we had something new to bring to that table.

Dining has also evolved. I wanted to do a couple of different shrimp recipes in the book. I did a traditional Vietnamese preparation, because I think people have brown sugar and fish sauce and those basic pantry items available to them. Every grocery store in America carries good fish sauce. The world has universalized so much that way, and that’s no longer a “weird ingredient.”

Americans don’t steam a lot. Most other cultures do. The French steam a lot of fish. There’s not an Asian country I know of where that’s not the case. When you tell people it’s as easy as putting an inch of water in a pan, putting fish on a plate, simmering the water, and then putting a lid on top of it—you’re steaming. If the fish is in the water, you’re poaching.

While it’s steaming, you make a little sauce out of stuff you have in your fridge. You can dip steamed fish into mayonnaise mixed with lemon juice. I opted for something with ginger, scallions, and soy sauce.

What inspired you and Barton to marry so many global flavors with seafood?

It’s the way we cook. We’re both globalists. Certain species are only found in one part of the world; some are tropical, some exist only in extremely cold water. However, fish swim and move around. So when you’re thinking about seafood, we think globally. I also believe, as a culture fanatic and someone who’s been preaching this kind of thing for decades, that the world is small. There are seafood powerhouses like India, Japan, Peru, the Nordic countries, France, Italy, America, Mexico. The world of seafood and its applications are absolutely incredible. And so I don’t think we ever, for a moment, considered not approaching these recipes from a global perspective.

Photo: Eric Wolfinger

Zimmern in the kitchen.

Rapid fire: Salt water or fresh water?

Salt.

Fresh or frozen?

Doesn’t matter. Irrelevant, because the technology has now reached a point where a lot of times when good freezing techniques are utilized, you can’t tell it apart from fresh fish. But what’s more important than fresh or frozen is, where is the fish from?

The most bizarre food you’ve ever eaten:

I remember going up into the mountains of Taiwan and eating a month-old, room-temperature-fermented pork dish. The pork is cut into strips, rolled into fresh-cooked rice, and packed into jars. And if you eat it after two weeks, it’ll kill you. But after six weeks, the good bacteria eats the bad bacteria, and you rinse it off, and all the funk and spoiled aroma and flavor is in the pork, but you can eat it. And I was just like, “Oh my Lord, how crazy is that?”

The recipe that raised you:

My grandmother’s roast chicken.

Kitchen tool you couldn’t live without:

This is going to sound so typical of every chef, but one really good, sharp knife. I have a couple of Shun carbon steel knives that stay sharp and last long. I can make adjustments for a shitty pan, but you can’t make adjustments for a bad knife.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.

Comments are closed.