Sarah Owens, author of “Sourdough: Recipes for Rustic Fermented Breads, Sweets, Savories, and More” (affiliate link), has already had several very creative careers. Originally a professional ceramic artist, she trained as a horticulturist at New York Botanical Garden’s School of Professional Horticulture, and then spent six years as the rosarian at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

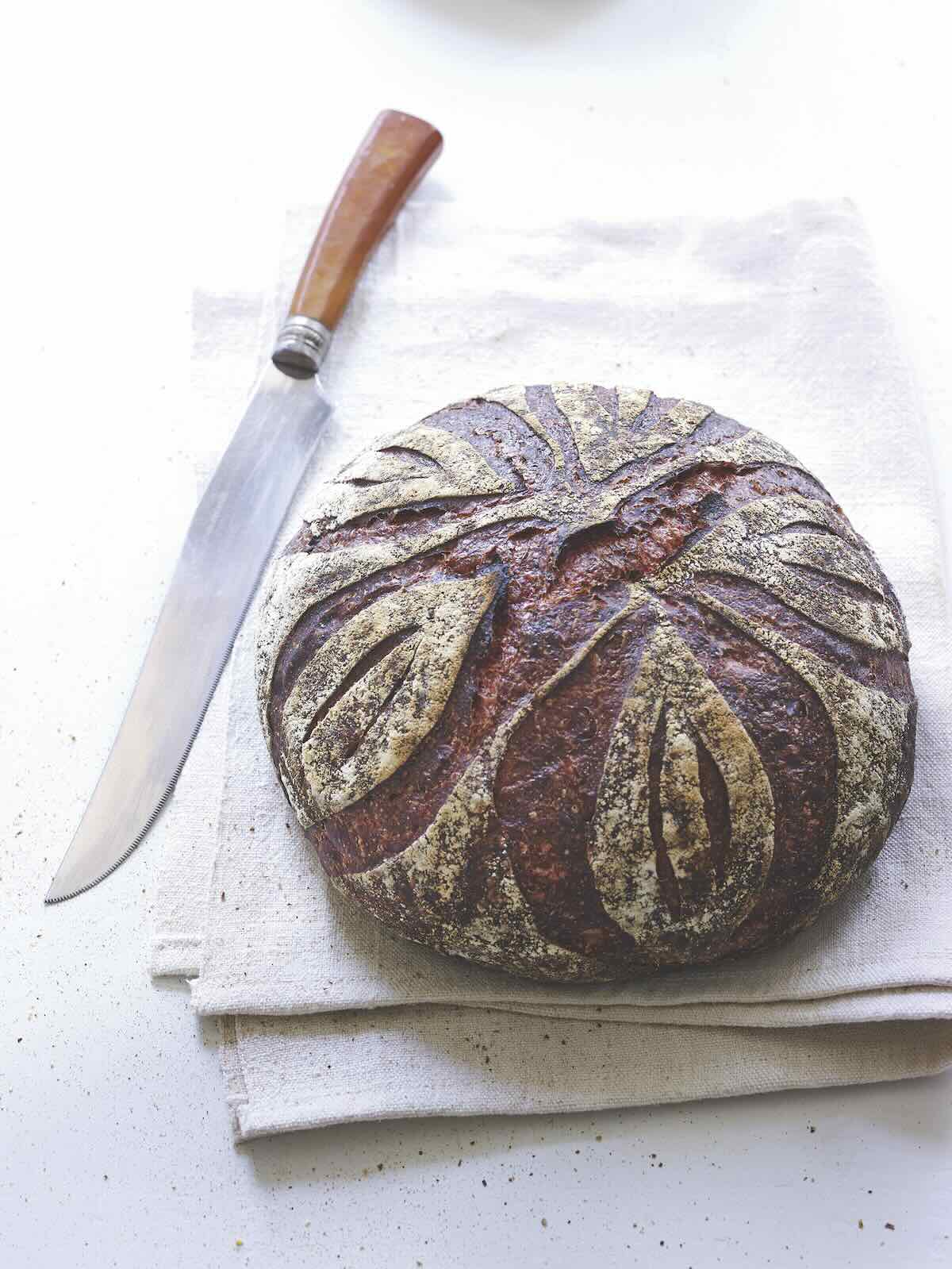

In 2013, Sarah founded a bakery in Brooklyn, then eventually moved to California, where she lives and gardens and bakes today. She is a popular teacher of baking workshops and offers online courses as well. (Photo top of page is the sourdough beet bread from the book.)

Plus: Comment in the box near the bottom of the page to enter the giveaway for a copy of the 10th anniversary edition of the book “Sourdough.”

Read along as you listen to the Oct. 6, 2025 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

sourdough (and gardening), with sarah owens

Download file | Play in new window | Duration: 00:27:39

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Margaret Roach: Are you in Sonoma County, Sarah? Is that where you are?

Sarah Owens: I am. I moved to California in January of 2020.

Margaret: Yeah. Oh, boy; that was a year. And before we talk about sourdough and baking, since we’re both gardeners, I wanted to ask you about your garden, in California. So it sounds like it’s about five years old, and what’s it like? Tell us about it.

And so when I think about how to plant, how to prune, how to do all the tasks that are necessary to maintain a garden, it’s on a very different schedule. And because of our zone, our growing zone, and all the different micro-climates here, it’s been an incredible experience and a growing experience for my skill set and also just learning how to fall into rhythm with what grows naturally here.

Margaret: So technically, what zone are you supposed to be there?

Sarah: Right here on this property, I would say we are probably a 9b, although if you go 20 minutes down the road, that could be a 9a, if you go 30 minutes inland, that might be a 10 [laughter]. It really depends.

And I’m in close proximity to the Pacific Ocean, so we get a heavy marine layer usually that rolls in the evening, and depending on what time of the year, it hangs very low throughout the morning. And that influences what can be grown here. It influences the moisture in the air, obviously, but also during the winter it can be quite a bit colder here than other parts of the county. And that also influences particularly the fruit trees that we can grow here.

Sarah: Yeah, it’s in an agricultural area, so I’m sort of wedged in between two vineyards that were formerly apple orchards. So this part of the county, because we are colder in winter, we have the chill hours that are necessary to grow some really delicious apples, and we still have quite a few heirloom apples on the property. But now it’s mostly Pinot noir, and grapes. And that’s also probably going to change in the next few years just because of the fallout of the wine industry here. But that seems to be the way things go agriculturally here.

But it’s a beautiful landscape, and I have about a quarter of an acre, so it’s not a very large garden. And I am in a rental house that I am very fortunate to be in close proximity to some wonderful neighbors and people who have lived here for decades and love this land very dearly. And so I’ve inherited different trees, mostly fruit trees, that I know the histories and stories of how and when they were planted. And the cottage that I live in is actually the former house of the orchard manager that lived here for a very long time.

Margaret: Oh, sweet.

Sarah: And that that orchard manager loved to do lots of different types of grafting. So as I’m speaking to you, I’m looking out the window at a citrus tree that has, to my knowledge, about four different types of citrus [laughter] that have been grafted all onto one tree, and right next to it, a very prolific lemon tree. And so I’ve been really lucky to have this abundance available to me.

Also, I live about a mile down the road from someone that I used to collaborate with quite a bit when I was at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden as the rosarian. And he is the proprietor of former Vintage Gardens and nursery that specialized in heirloom roses. Now it’s become a nonprofit, and they do rose sales on site twice a year. And so I’ve been very lucky to be able to resume a close friendship with Gregg Lowery, who is the rosarian of vintage gardens, and acquire some of the most amazing roses that you could ever grow here in a very different climate. So I have about 50-plus roses that I’m-

Margaret: Oh dear! [Laughter.] It’s addictive. It’s addictive.

Sarah: The obsession, I don’t think it ever goes away, but it’s been really interesting because the climate is so different. The roses, their habits, their blooms, how you prune and take care of them when you prune and take care of them is a completely different schedule. And sometimes roses that I grew for many years and became very acquainted with, sometimes it’s hard for me to even recognize them here because they’re five times the size of what they were in New York, or they bloom not just once during the spring, but two more times, in the late summer and then again in early winter. And it’s a whole different world, and I’m having a lot of fun with it.

Sarah: I haven’t.

Margaret: Oh, well, you’ve got to get it. It’s fabulous. So besides bringing to light all of the living creatures that we inadvertently share our homes with—crickets in the cellar and silverfish and a zillion kinds of spiders and this and that and the other thing, all these arthropods and so forth—we also live with microbes, like in our sourdough starter.

And one chapter in the book is this story of this experiment where he’s just really fascinated with the microbes in sourdough, and he develops an experiment working with some bread-flour company or F-L-O-U-R company or bread company or something in, I think it was Germany or Belgium or somewhere. Anyway, to do this test, this experiment, they brought together a bunch of sourdough experts, expert bakers, from all over the world to this sort of suite of test kitchens, as I recall, they gave them identical ingredients to create their starter. So they have these laboratory-like kitchens, identical ingredients, the same flour, everything the same.

But of course when the starters were done, none of them were the same. None of them had the same, I don’t know if you would call it flavor or smell, because what I think is, and maybe it’s in Korea, it’s known as “hand flavor” because of the microbes of us. [Laughter.] Sourdough’s alive, and so are we.

I mean, I’m sorry, that’s sort of a long-winded story, but it just delighted me so much, the idea that there’s this signature in working with sourdough, right?

Sarah: Yes, absolutely.

Margaret: So I wanted you to tell me a little bit about that, if that sort of resonated with you.

Sarah: It does. And in fact, I had forgotten that I had worked with a scientist named Erin McKinney, who is also a lecturer and scientist at North Carolina State University, who has worked with Rob Dunn. We were able to do a workshop together in 2019 in North Carolina. And it was fascinating to me, because she really brought the scientific element to something that I often approach very intuitively, at least at this point in my baking practice.

But it’s so fascinating because we are learning so much more about this microbial world. And as a gardener, I think that there has been a lot of traction in terms of understanding and learning more about the relationships that plants have with soil microbes. And that’s really where I started with my understanding of sourdough, was having this appreciation for the unseen world of soil, and then learning how to apply those concepts to a sourdough starter.

But fortunately, we have many different collaborations and labs and universities that are working toward further understanding these relationships. And Erin McKinney helped me understand that within a sourdough culture, often when I teach about it, I speak of it, I sort of reduce it down to bacteria and yeast, but she really helped me understand that there can be up to 70 different microbes, species and subspecies of microbes, within one culture.

And that culture, that sourdough culture, is influenced by so much by the baker themselves, whether they are a gardener, whether they have pets [laughter], all these different aspects that we may or may not think about on a daily basis. But all of that contributes to, like you said, the signature flavor.

Margaret: And in that experiment, they also swabbed the hands of each baker, and you could tell whose starter was whose from that as well. [Laughter.] The chemistry was the same. It’s crazy. It’s totally crazy. It’s wonderful. And it’s alive, right? It’s literally alive. And you write about in the book that’s just out again in the 10th anniversary edition, the book “Sourdough”—you encourage each of us to experience sourdough in all of its four seasons, because you say that we should try to see firsthand how our starter changes character in each of those seasons. Again, it’s alive; it’s not the same on a cold wintry day, a dry day as it is in the humid heat of summer. And so tell us a little bit about that. So it changes too, right, even the same starter changes?

Sarah: Yes, the composition of the starter, the behavior of the starter, changes, and the way that we must respond to that also, of course, changes, depending upon what our desired outcome is. And in the book, there are many different recipes. Some of them use starter as a leavening agent, and some of the recipes use it more as an ingredient.

But when you are using sourdough starter as a leavening agent, you are trying to encourage the activity of both yeast and bacteria and the yeast in particular, the byproduct of yeast fermentation is carbon dioxide gas, and that is what leavens our bread. So if we’re making bread, if that’s the desired outcome is to have a loaf that has a good rise and a good oven spring, and all of a sudden it is turned cold and rainy—which has happened today as we’re recording this podcast, we got the first rain of the season; very exciting—hen we really have to take into consideration how the temperature and the humidity and all of these different environmental factors are going to influence the speed in which our dough ferments.

Margaret: So in learning to be not a master, but more experienced with sourdough, one has to take note of these things, has to patiently observe, I guess, and feel our way through it, right? I mean, because it’s not just something you can say, “Put a cup of this and put a tablespoon of that and a quart of this, and there you go; put it in a 350 oven. Thank you very much.” [Laughter.]

It’s about percentages, right? It’s not that way. It’s about percentages—you call it “the baker’s math” in the book—with sourdough, that every ingredient is expressed as a percentage of the total weight, the total weight of the flour that’s considered the 100 percent, the flour weight. And how much hydration the starter has, and oh my goodness. [laughter]. So we really have to be open to learning and understanding and embracing, again, this very exciting, very versatile living thing that can do so much. And as you say, not just to make bread rise, but as a flavor, as an ingredient as well in other recipes. Pretty fascinating stuff.

Sarah: It is. It is. And it’s something that I think it requires presence, and I find that gardening and baking, they have so many parallels. And this requirement of us to really be present with a dough and be observant and take in what the dough is trying to tell us, in addition to just simply the craft of learning baking, they’re kind of two different things.

And I think that I really try to encourage folks who’ve never baked bread before, whether with sourdough or with yeast, to really start with a recipe that speaks to them that seems appealing, that seems delicious, and repeat that recipe many different times if you can, to just acquire the skills that are necessary. And this is something that whether you’re learning ceramics or gardening or baking, you have to learn the technique or the skill before you can really understand the nuance of something or learn how to respond to something intuitively.

Margaret: Yeah, hopefully you get a rhythm, you get a groove, you find your way with it, and then once you have that, you can experiment a little more [laughter].

Sarah: And you can make it as complicated as you want at that point.

Margaret: And we do, and we sometimes do. So I’m including this link to our sort of vintage conversation from, again, almost 10 years ago, like I spoke about in the introduction, of the actual how-to of a starter making, so that people might like to listen to that and be a recipe and so forth as well.

But I was curious, you say in the start of the 10th anniversary edition, that one thing that has changed a lot is the availability in those ensuing 10 years is the availability of different kinds of flours then were available back then. Does that, and then does that mean different starters? Tell us a little bit about sort of what’s going on with flowers and does that affect the starters? And every time I say flours, speaking to you as a gardener, I want to spell it out again. I’m sorry. It just keeps sounding wrong to me [laughter]. [Below, from the book, Tomato and Labneh Galette.]

And not all wheat is made the same. I was just in Italy, in Southern Italy, where durum wheat is the predominant type of wheat grown there, because of its very dry, drought-like conditions during the summer and very intense heat. That type of wheat would not do very well in a wet, humid environment during the summers of British Columbia, for example.

And so these various smaller-farm systems have moved toward very specific types of grains, whether it be wheat or rye, barley or other types of grains. And those grains are becoming more available to bakers, also being milled in very different ways. So we’ve primarily learned baking over the last 150 years from roller-milled flour. This is a very industrial process. And now we’re seeing these smaller farming systems turning to stone milling, and stone milling can retain all parts of the grain: the bran, the germ where all of the flavor and the oils reside, and also the endosperm.

And so when we’re getting whole-grain flour, that’s been grown organically and stone milled, this type of flour, you can imagine how the microbes in a starter are going to respond to this type of flour. There’s so much food [laughter] available to our starters, to our dough. Interesting.

So fermentation really goes crazy when you feed a starter that’s been used to being fed with store-bought industrial flour that you buy off the shelf, and then you feed it stone-ground, freshly milled whole-grain flour, the starter just kind of explodes in activity [laughter]. And if you’re used to it taking eight hours to double in size, all of a sudden it takes four to six hours at the same temperature.

It’s a whole other creature, not just in its behavior, its fermentation behavior, but also in its flavor, again, because you’re retaining with the stone milling. And often these smaller systems are turning toward, not always, but often turning toward heirloom varieties of grains that were really grown more for flavor than for yield.

Then we’re also getting these really complex flavors and even colors of bread that we haven’t seen before. And so it’s a whole other world. It’s like a painter that only had red, blue, and green in their palette, and now there’s like 25 different colors to play with [laughter]. It’s a totally different canvas. It’s a totally different landscape.

And so I think when I wrote “Sourdough,” when I wrote my first book, I was beginning to play with some of those flowers. I was beginning to work with einkorn and emmer and spelt, and some of those are definitely featured in the book. But now we’re seeing so much greater access to these different types of flours, and it’s really a very exciting time to be baking. [Below, from the book, Savory Kale Scones.]

Sarah: I do. I have one, have one starter. Sometimes I do keep two starters. Sometimes I’ll keep a brown rice starter to make gluten-free breads, and then a wheat starter. When I was in New York the last five to seven years I was in New York, I kept primarily a rye-fed starter. And when I moved to California, I think my starter was a little upset with me because it just went, it turned very strange. It was a strange flavor. It was a strange odor. So I switched when I moved to California to feeding my starter with whole wheat.

And I have kept it since 2021. I’ve kept the same starter fed primarily with whole wheat. And that starter, I travel a lot now to teach, and when I travel, I travel with it as a stiff starter. And I refer to it as Stiffy, and I revive Stiffy wherever I go using whatever the local flour is. And then I work with that starter in that location. And then at the end of the workshop or the retreat, I then create another stiff starter. I bring it back with me to California.

And in this way, I feel like I’m incorporating the microbial footprint of everywhere that I’ve been, in addition to the footprint of my home in California and the flours that I use here. And it’s become a very resilient, very active starter. And it’s been fascinating to watch it. I almost want to create a travel blog [laughter] just based around The Adventures of Stiffy because it’s such a creature. Crazy.

Margaret: Well, it’s been fun to talk to you again, and I hope we won’t wait another 10 years. Sarah Owens, author of “Sourdough,” which is just coming out in its 10th anniversary edition. And I’ll talk to you soon again, I hope.

how to make sourdough starter

enter to win a copy of ‘sourdough’

Have you ever baked with a sourdough starter? Tell us!

No answer, or feeling shy? Just say something like “count me in” and I will, but a reply is even better. I’ll select a random winner after entries close Tuesday Oct. 14, 2025 at midnight. Good luck to all.

(Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

Comments are closed.