Twenty-five years ago, Philadelphia officials approved a proposal for a small site along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to house a museum dedicated to the work of Alexander Calder (1898–1976), the Pennsylvania-born artist best known for his colorful mobiles and creaturely static sculptures, which feature in countless public spaces worldwide. Tadao Ando received the commission and, soon after, proposed a design that left much of the ground level as green space and placed the galleries underground.

Now Philadelphia is finally getting its Calders, and everything is as it was supposed to be, just a little different. The list of philanthropic backers has changed, as has the architect—it is now Herzog & de Meuron—but the site is the same, and the galleries are still below grade. We are not, however, supposed to call the project a museum, a point upon which both the architects and the institution insist. Christened Calder Gardens, it has an artist at its center but no permanent collection of artwork—meaning that the architects and their collaborators, notable among them the garden designer Piet Oudolf, had to design spaces suited to hosting an ever-changing array of works. Perhaps forgoing a permanent collection was an act of curatorial bravery, but it may also reflect the wishes and interests of Calder’s heirs, who control a vast trove of artworks through the New York–based Calder Foundation. The earlier, Ando-designed iteration of the project unraveled in 2005, after backers accused the foundation of reneging on a pledge to provide enough pieces to form a collection. For the new version, the foundation will instead provide a rotating array of Calder’s works for temporary display.

The lack of a collection was not the only unusual thing. There was also the peculiarity of the site, which, though close to such institutions as the Barnes Foundation, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Rodin Museum, is awkwardly sandwiched between a sunken expressway and an eight-lane parkway that has never come close to living up to its Parisian inspiration, the Champs-Élysées. Further complicating matters, an undocumented water main was discovered during the design process, and, even after it was relocated, easement rules dictated that no underground spaces could be excavated near the front of the site.

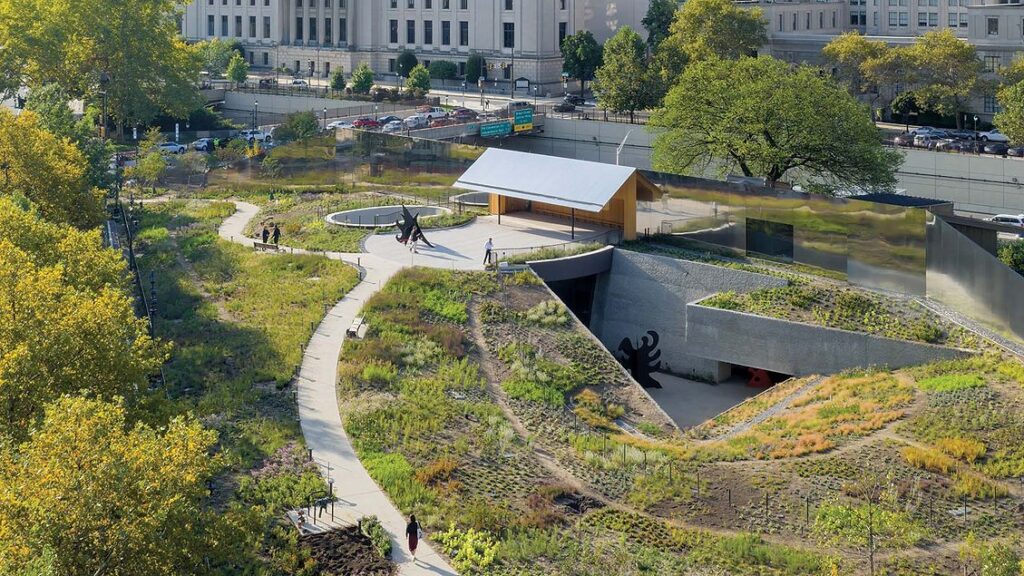

In response, Herzog & de Meuron’s 18,000-square-foot building takes the form of a narrow one-story bar, its front clad in reflective stainless steel, set back against the highway; from the parkway, it appears as a shimmering wall, giving spatial definition to a site that previously had none and blocking the roar of the highway. To reach it, you take one of two paths up a gentle slope through perennial-filled gardens, which Oudolf says offer a “wide spectrum of experience,” transitioning from tree-heavy areas on the edges of the site to a mix of prairie plantings at the center. There you encounter a disk-shaped entry plaza that houses the sole publicly accessible sculpture and offers views on both sides to outdoor exhibition spaces below. The wall, the disk, the sunken garden: from these three elements emerges a tight spatial choreography through which all visitors must pass to enter Calder’s world of color and abstraction.

At the entry plaza, wood combines with reflective stainless steel. Photo © Iwan Baan

Where the disk bites into the building’s front, a section of the stainless-steel wall appears to have swung forward, as if hinged at the top, creating a canopy over a hemlock-clad outdoor entry area (the overall effect is something of a cross between the firm’s 2012 Parrish Art Museum on Long Island and its 2015 Miu Miu store in Tokyo). From here, you turn right to enter the lobby and gift shop, also clad in hemlock, and, once you buy a ticket—adults pay $18—you proceed down to a mezzanine space overlooking a double-height gallery. To your right, the back wall is bisected by a strip window that offers an unexpected glimpse of cars racing down the highway. If the building is “almost like a chapel,” in the words of project architect Jason Frantzen, this view serves as a momentary reminder of the indifferent world beyond.

The back wall of textured concrete and wood is bisected by a strip window. Photo © Iwan Baan

A mezzanine overlooks a double-height gallery. Photo © Iwan Baan

A miniature mobile hangs in a niche. Photo © Iwan Baan

There is yet another leg to the prescribed journey: a second stair, this one dark and cave-like and rendered in a rough shotcrete, snakes farther down, passing by a rounded glass portal, behind which hangs one of Calder’s miniature-scale twisted-wire mobiles. This niche turns out to be the smallest of an array of exhibition spaces that together make up the underground level. Notable among these are a central “open-plan gallery” with a convex ceiling that dramatizes the presence of the disk above; an all-white “apse gallery” where the floor, walls, and ceiling, joined by curving edges, merge into an enveloping off-white cocoon; a “sunken garden” that cannot be entered but will house sculptures surrounded by a ring of draped plantings, which can be gazed at through floor-to-ceiling windows; and a “vestige garden,” an accessible outdoor space bounded by textured concrete walls placed where long-demolished buildings once stood.

The level of execution is impressive—during construction, Swiss and German builders were brought in to train the local contractors—and the subtlety of material, light, and form that distinguishes the exhibition spaces speaks to the decades of experience Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron have in designing with and for art, a history that goes back to their collaboration with Joseph Beuys at the 1978 Basel Carnival. The architects sought for the artworks “to express their incredible diversity and ambiguity” as Herzog puts it in a brief book about the project, and they did so by creating rich spatial variety that also helps address the lack of a permanent collection: each space possesses a distinct character with which any number of artworks may enter into dialogue. The possibilities are limitless, at least in theory, and Calder Gardens promises in its guiding principles that it will “always be open to interpretation.”

Welcoming the interpretation of art displayed in galleries: perhaps Calder Gardens is a museum after all. And, like most other museums, it makes use of its physical container—its architecture—to impose strict bounds on openness: that is, to make objects accessible while controlling exactly how they are accessed. The public garden will no doubt be pleasant to move through, but it offers few opportunities for lingering—no tables, no open space, no winding pathways to explore. And the quiet double function of Herzog & de Meuron’s long entry sequence is to create a gateway between the at-grade public realm and the below-grade private one, a gateway where staff will take tickets, remind you to wear your backpack awkwardly on your chest, and warn you not to eat, drink, touch anything, or be too loud. Unsurprisingly, such constraints do not originate with the architect. The Calder Foundation is no doubt concerned with protecting its prime cultural and financial assets, and earlier design concepts where sculptures were placed near the parkway or where visitors could directly access the below-grade spaces were rejected.

Yet, familiar as it is, the museum setup is notably different from that of so many Calder sculptures, embedded as they are in such public spaces as Federal Plaza in Chicago and outside the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Just a block from this project, two of the artist’s tapestries hang unceremoniously in a social room in Philadelphia’s central library. There are yet more Calders on the parkway. At the road’s southeastern end stands Philadelphia City Hall, the exterior of which is adorned with hundreds of sculptures by Alexander Milne Calder, Calder’s grandfather. And, less than a mile up, at the center of Logan Circle, is Swann Memorial Fountain, long a beloved place for children to swim and climb on the sculpted figures and water-spouting turtles by Alexander Stirling Calder, Calder’s father.

This interweaving of family history, sculpture, and public space is a singular thing, and it is one of the main reasons that Calder Gardens ended up where it is. Yet the paradox of this project is that its very rejection of the museum paradigm—its forgoing of a permanent collection that could be freely sited and made freely available to the public—forces it to retreat from the civic ambitions shared by three generations of sculptors, back into the hermetic space of the museum.

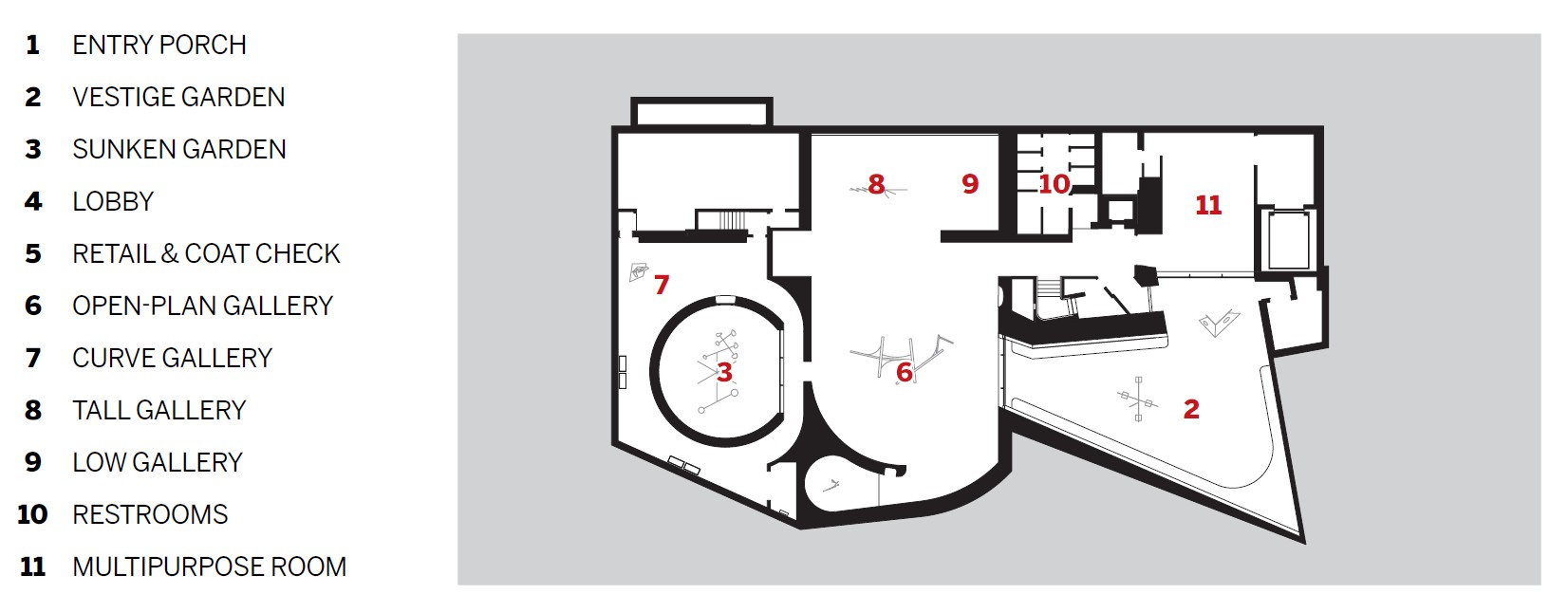

Image courtesy Herzog & de Meuron, click to enlarge.

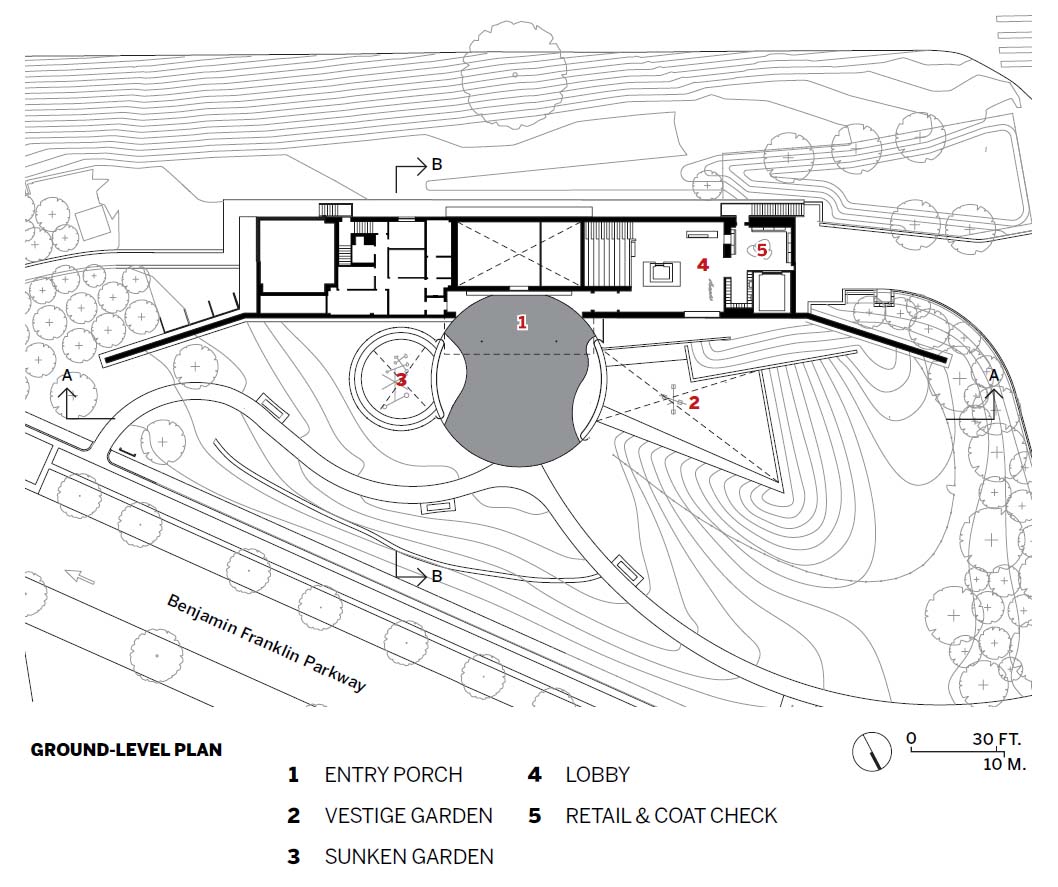

Image courtesy Herzog & de Meuron, click to enlarge.

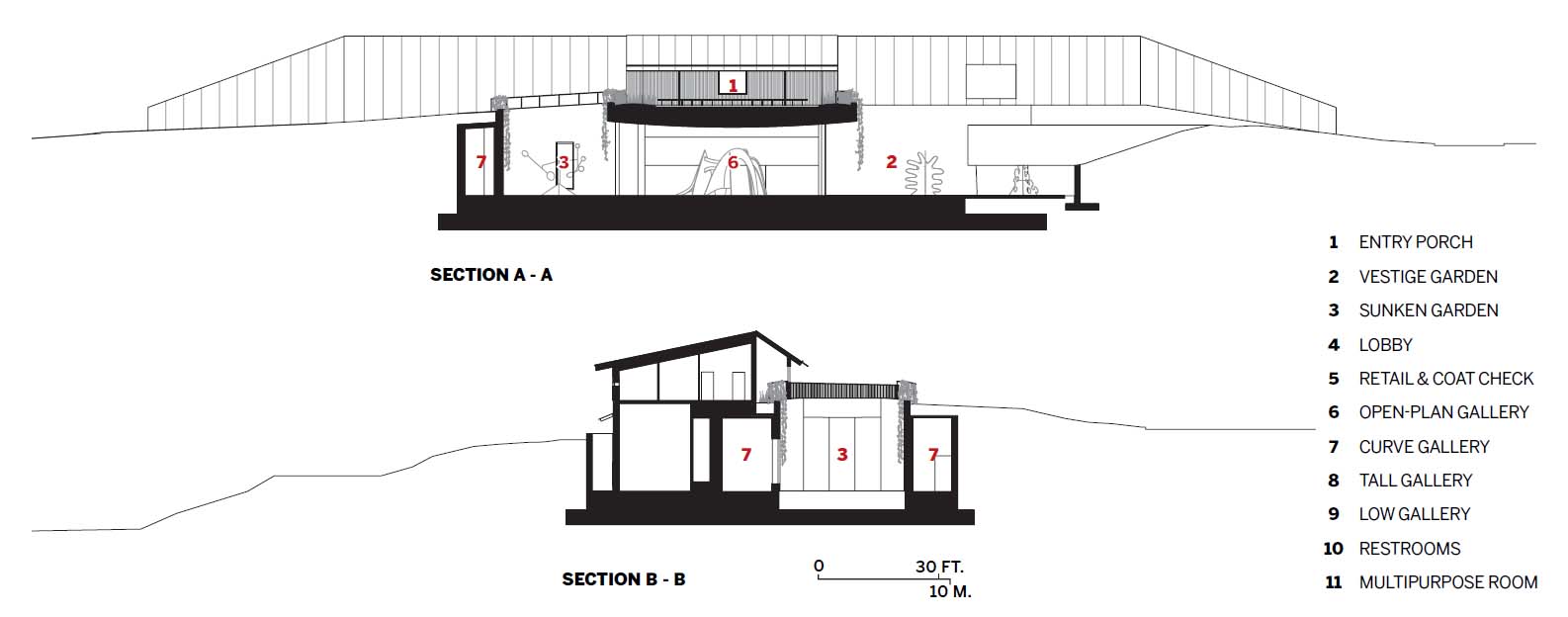

Image courtesy Herzog & de Meuron, click to enlarge.

Comments are closed.