Desert Botanical Garden rescues rare cacti confiscated at border

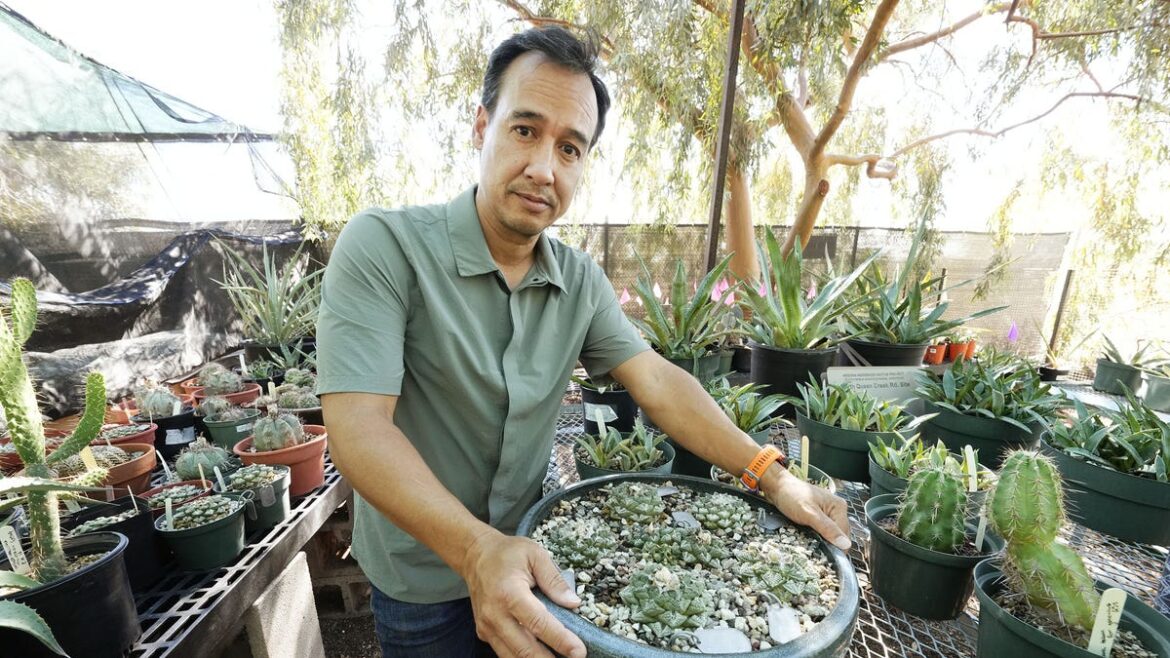

Steve Blackwell, the Conservation Collections Manager, oversees the collection of rare and endangered plants, seed bank, and tissue culture lab.

The Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix is one of 62 other gardens, arboretums and zoos that take in rescued cactus and succulents.Cactuses are the fifth-most endangered group of living things in the world, in large part because of the illegal cactus trade.Rescued cactuses can’t be returned to the wild, but can produce seeds for future projects and help educate the public on the dangers of plant poaching.

Under a tent shrouded in shade cloth at the Desert Botanical Garden, a place known for its showy cactus displays and wildflower blooms, sits a curious collection of inconspicuous plants that could be easily overlooked by the untrained eye.

Among the trays of saguaro cactus seedlings, planters with small, star-shaped cactuses are marked with dog tags reading “PLANT RESCUE” and the obscure scientific name: Ariocarpus kotschoubeyanus.

For international collectors and cactus enthusiasts, these small plants, known as living rock cactuses, are a prized rarity worth violating federal law and an international treaty.

Once bound for the thriving black market, these cactuses are now contraband.

“Some of these cactus collectors are pretty hardcore. And they’ll do anything they can to round out their collection of cacti,” said Steve Blackwell, the conservation collections manager at the garden.

Since 1996, Phoenix’s Desert Botanical Garden has served as a plant rescue center for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, providing refuge to plants confiscated by federal authorities at border crossings and ports of entry.

Along with 62 other botanical gardens, arboretums, zoos and research institutions across the country, the Desert Botanical Garden specializes in rescuing the cactus and succulents.

When the 400 individual living rock cactuses arrived at the garden in 2023, they were in bad shape, dried up and root-less. Blackwell and his team got to work rehabilitating the declining species native to Mexico.

Wild cactus specimens are highly sought-after

Cactus are considered the fifth most endangered group of living things in the world, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Among their primary threats: the illegal cactus trade, a trend that has only grown since plant collecting grew popular on social media during the COVID-19 lockdown.

According to a 2015 IUCN Report, 86% of threatened cactuses used in horticulture are collected from wild populations, with collectors in Europe and Asia being the biggest perpetrators.

Specimens taken from the wild are more sought-after than their ethically grown counterparts because of their rarity.

In a 2022 survey of 418 cactus hobbyists, 11% of the respondents self-reported that they were not in compliance with the international agreement regulating plant trade.

Other major threats to cactuses worldwide include habitat loss and climate change.

The living rock cactuses and other rescued plants at the Desert Botanical Garden cannot be returned to the wild because their genetics could cause adverse effects to existing populations if not placed in the exact area where they were taken.

Once confiscated, the plants spend the rest of their lives at the botanical garden, where their seeds can be banked for future conservation projects.

They can also be used as teaching aids when educating the public on the dangers of plant poaching, an issue Blackwell says many people aren’t aware of.

“People are dumbfounded by the whole thing,” said Blackwell. “Not only can we highlight the impact that poaching has on wild populations, but also, we can stress the fact that it is illegal to take anything from the wild without permits.”

Arizona’s native cactuses are vulnerable to poaching

Between 1,500 and 1,800 different species of cactus grow in the Western Hemisphere, ranging from southern Canada to Patagonia near the tip of South America.

Though Mexico is considered the most cactus-diverse region on Earth, with approximately 850 species of the spiny succulents, Arizona’s native, endangered cactus are also vulnerable to poachers hoping to satisfy international collectors and local landscapers.

In 2007, two poachers were caught stealing 17 saguaros from Saguaro National Park and surrounding county land. The two Tucson residents pleaded guilty in federal court in 2009, where one was sentenced to eight months in federal prison and the other to six months of home confinement and 100 hours of community service.

In 2009, the National Park Service and nonprofit partner, Friends of Saguaro National Park, began inserting microchips into vulnerable adolescent saguaro cactuses to aid in tracking stolen plants used for landscaping. The microchips are the same as the kind used to identify lost pets.

But Arizona’s smaller endangered cactus species, like the acuña cactus, the Fickeisen plains cactus and the Arizona hedgehog cactus, are increasingly vulnerable to poaching. Though more difficult to find, the smaller cactuses are easier to steal and transport.

“The more rare a plant becomes, the more valuable it becomes,” said Blackwell “That means the ones that are already endangered are put at higher risk.”

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as CITES, is an international agreement governing the international trade of wildlife and plant specimens.

Today, the CITES agreement protects over 40,000 species of plants and animals across the globe, including the living rock cactuses rescued by the Desert Botanical Garden and Arizona’s native endangered cactuses.

John Leos covers environmental issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to john.leos@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust.

Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook and Instagram.

Comments are closed.