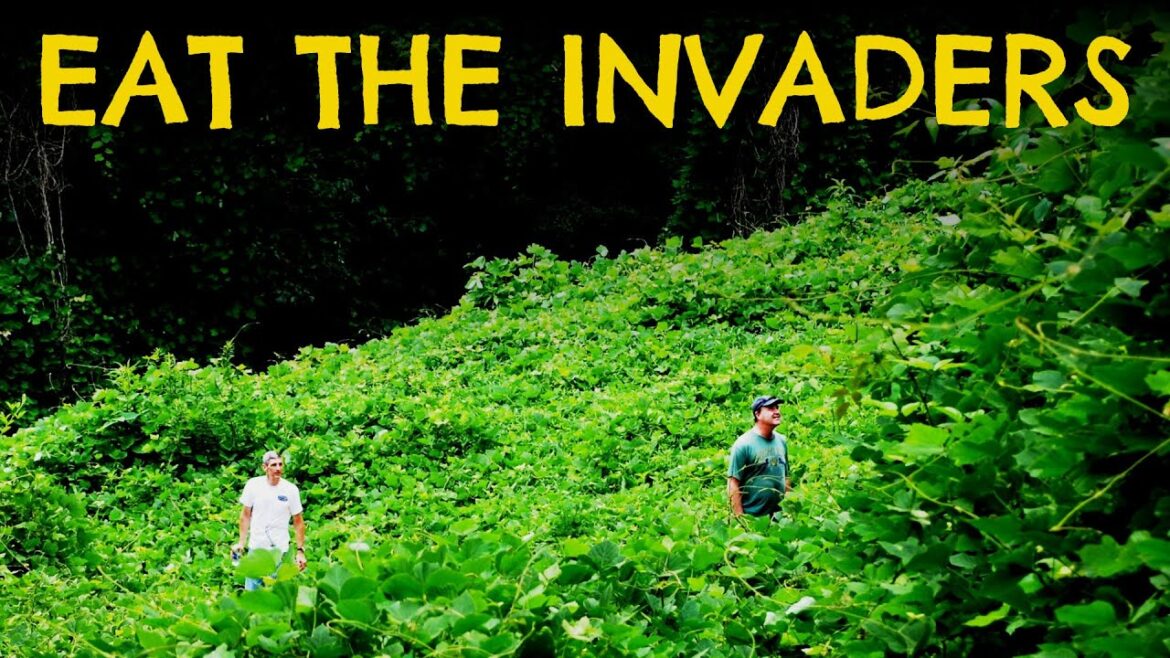

Invasive weeds are taking over North America’s ecosystems—but what if some of them could help us eat our way to restoration?

In this episode of Edible America, we explore 10 edible invasive plants that are disrupting the landscape and stocking our wild pantry. From Garlic Mustard to Kudzu, Himalayan Blackberry to Wild Fennel, discover where these plants came from, how they got here, and how you can turn an ecological problem into a foraging opportunity.

🌱 Learn how to safely harvest and prepare each plant

🌎 Support native ecosystems by removing invaders with your fork

🍇 Rediscover forgotten flavors and surprising nutrition

This is food sovereignty with dirt on your hands. Subscribe for more stories, guides, and recipes from the front lines of foraging and resilience.

Eat the Weeds.

🔗 Follow us:

YouTube: @edible_america

Substack: edibleamerica.substack.com

TikTok: @edibleamerica

Ko-Fi: ko-fi.com/edibleamerica

🌾 Let’s reclaim the landscape—one invasive plant at a time.

Join the substack for tips, recipes & more – https://edibleamerica.substack.com/

Buy me a Coffee – https://ko-fi.com/edibleamerica

0:00 Introduction to Edible Invasive Plants

0:28 – Can You Eat Garlic Mustard? Invasive in shaded woodlands of Northern California, especially around the Bay Area and Sierra foothills.

1:28 – Is Japanese Knotweed Edible?

2:21 – What Are Autumn Olive Berries Good For?

3:12 – Can You Eat Kudzu?

4:13 – Are Himalayan Blackberries Safe to Eat?

5:01 – What Is Wild Fennel Used For?

5:50 – Can You Use Mullein for Tea?

6:38 – Is Lamb’s Quarters Edible?

7:18 – Can You Eat Dandelions from Your Yard?

8:07 – What Is Creeping Charlie Good For?

8:48 – Why Eat Invasive Plants?

⚠️ Disclaimer: The content provided on Edible America is for informational and educational purposes only. Always positively identify any wild plant before consuming it, as some edible plants have toxic lookalikes. When in doubt, consult a local expert or reliable field guide.

The host(s) of this channel are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use or misuse of the information presented. Foraging laws and regulations vary by location—please forage responsibly, ethically, and legally.

Across the US, invasive plants are spreading fast, choking out native species, reshaping ecosystems, and frustrating land managers everywhere. But here’s the twist. Some of them are delicious. Today, we’re digging into 10 edible invasive plants, where they came from, how they got here, and how you can help restore balance with your fork. [Music] Garlic mustard was brought to North America by European settlers who valued it as a vitaminrich spring green and natural remedy. Unfortunately, it quickly escaped gardens and found its way into forests where it thrives in the understory and aggressively displaces native wild flowers. Now considered a highly invasive species, garlic mustard is especially prevalent in the eastern and midwestern United States from New England to the Great Lakes region and as far south as the Carolas and Tennessee. It’s also spreading into parts of the Pacific Northwest and beyond wherever moist shaded woodlands provide ideal conditions. Its tender spring leaves have a distinctive garlicky bite and can be used much like arugula or mustard greens. Try tossing them in salads, wilting them into pasta, or whipping up a sharp zesty pesto. The best part, harvesting garlic mustard helps reduce the spread and gives native species a fighted chance. Originally introduced as a garden ornamental due to its attractive bambooike stalks and heart-shaped leaves, Japanese knotweed is now infamous for its destructive tendencies. Its deep risomes can tear up foundations, clog waterways, and are notoriously difficult to remove. Japanese knotweed thrives in much of the northeastern United States, the Pacific Northwest, and parts of the Midwest, and Appalachian, especially in disturbed areas with moist soil like river banks, roadsides, and vacant lots. It’s rapidly spreading in temperate regions across the country. However, in early spring, the young shoots are not just edible. They’re quite delicious. Tart and juicy like rhubarb. They make excellent additions to crumbles, compost, syrups, and pickles. Just be cautious not to spread the roots or discard them carelessly. Autumn olive was once considered a solution. It was planted across the US to combat erosion and provide food and shelter for wildlife. But it spread far beyond its intended range and now dominates roadsides, pastures, and disturbed habitats, especially throughout the eastern and Midwestern United States from New England and the Mid-Atlantic down through the Southeast and west into the Great Plains. Come fall, it bursts with thousands of shimmering red berries speckled with silver. These berries are not only edible, they’re nutrient powerhouses packed with lysopene and antioxidants. Eating raw, they’re tangy and slightly sweet. Cook them down to jams, fruit leathers, or syrups, and you’ll wonder why you ever ignored them. Every berry you gather helps reduce its reproductive power. Kudzu was held as a miracle plant for the American South. Fast growing and resilient, it was widely planted to prevent erosion. But with no natural predators and ideal conditions, it exploded. Now draping entire forest, telephone poles, and abandoned structures in green curtains. Kudu thrives in the southeastern United States, particularly in states like Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and the Carolas, but it has crept as far north as Illinois, Pennsylvania, and even parts of New York. It flourishes in warm, humid climates and disturbed areas with full sun. Despite its infamy, kudzu is surprisingly versatile. The leaves are edible raw or cooked like spinach. The starchy roots can be processed into flour, used as soup thickener or made into jellies, and the fragrant purple flowers yield a floral syrup or even wine. Use it in moderation though as large amounts of kudzu may cause digestive upset in sensitive individuals. Introduced by fame botnist Luther Burbank for its fruit, the Himalayan blackberry quickly escaped cultivation. With dense thorny brambles and tenacious root system is now one of the most widespread invasive species on the west coast, especially in Oregon, Washington, California, and British Columbia, but also found in parts of the Pacific Northwest, inland, and beyond wherever mild, wet winters and disturbed land give it an edge. Luckily, the berries are incredible, large, juicy, and rich in flavor. They shine in pies, cobblers, jams, or straight off the cane. Foragers can help by harvesting the fruit, or even using the canes for basketry or fuel. Eat your field and restore some space for native plants. Wild finel now grows abundantly along roadsides, fields, and open spaces, especially in the coastal states like California, Oregon, and Washington. It is also naturalized in parts of the northeast and Mediterranean-like climates across the southern US. Its feathery fronds, bright yellow flowers, and strong anise scent make it easy to spot and smell. Every part of the plant has culinary uses. The leaves can be chopped into salads, sauces, or seafood dishes. The seeds are sweet and pungent, perfect for baking or tea. The stalk can be brazed like celery. It spreads easily and displaces native grasses, so gathering finel can be both tasty and beneficial. Just beware of its poisonous lookalikes like him. Always confirm ID. With its towering flower stalks and thick fuzzy leaves, mulling is a standout in dry meadows, hillsides, and roadsides across much of the United States. It thrives in all but the wetest or most heavily forested regions, especially in the west, southwest, great plains, and parts of the northeast, wherever disturbed, sunny ground is plentiful. Early settlers brought it for its medicinal qualities, especially as a remedy for cough and respiratory issues. The soft leaves can be steeped into teased or used as herbalases. The flowers are great for infusing into oils or syrups to ease sore throats. It’s not as aggressive as some other invaders, but does colonize open ground quickly. Consider this one a helpful if pushy neighbor. Sometimes called wild spinach, lamb’s quarters grows prolifically in disturbed soils, gardens, construction sites, vacant lots, even cracks in the pavement. It thrives across the entire United States from coast to coast, especially in temperate regions with rich or compacted soils. Wherever the ground’s been turned, it’s likely to show up. The tender young leaves can be steamed, sauteed, or eaten raw in salads. High in calcium, iron, and protein, it rivals kale and beats many supermarket greens. Yet, it’s often pulled and tossed like trash. If you find it in your garden, don’t weed it out, eat it. Dandelions aren’t just edible, they’re one of the most useful plants around. Found in every US state and nearly every corner of the continent, they thrive in lawns, fields, sidewalks, and roadsides. Wherever there’s a patch of open soil or grass, every part of the plant offers something. Young leaves add a bitter, nutrient-dense pop to salads. Roots can be roasted into a coffee alternative. Flowers can be made into syrup or wine, and pollinators love them. Dandelions bloom early, providing nectar when few other flowers are available, helping sustain bees and butterflies. Their tap roots ariate soil and bring nutrients up from deep layers, actually improving lawn health. Instead of spraying them, maybe start appreciating their bright resilience. Also known as ground ivy, creeping charlie forms thick mats that can overrun lawns, gardens, and shady spots, especially in the eastern and central United States from New England and the Midwest down through the south. It thrives in moist, shaded areas and disturbed soils, making it a persistent presence in suburban lawns and woodland edges alike. But before you curse it, try tasting it. It has a mild minty flavor and was once used in beer brewing before hops became standard. It makes a delicate tea and can be added fresh to salads or cooked into greens. Harvest it before it takes over and you might find a new appreciation for this lawn lurker. Invasive plants crowd out wild flowers, destroy native habitats, and reshape ecosystems. But when the grocery bill climbs higher and resilience matters more than ever, maybe it’s time to think differently. Maybe the best tool against an invader is a fork. So forage wisely, learn what grows near you. Share what you gather. And remember, even the plants that don’t belong here might have something worth savoring. Subscribe to Edible America for more foraging tips, recipes, and food sovereignty stories. Comment with your favorite edible invasive or one you’re curious about. Until next time, keep your eyes open and your roots deep.

33 Comments

Could you do a video on black mustard greens and how to find them. My grandmother knew what to look for but I was young and didn’t pay attention. Great video. Subscribed.❤

I use dandelion every year, Wooly Mullien is part of my asthma medicine, lamb's quarter is always on my menu, and i have gathered wild fennel from roadsides for much of my adult life. Blackberries are a staple for us, and so are the many forms of wild mustards.

Lots of great information! I have nearly all of these plants growing on my 2 acre property, in Northern Michigan. I have a long hedgerow of Japanese Knotweed.

Dandelion, lamb's quarters, wide leaf plantain, Charlie, mint, red white and yellow clovers grow in my garden. All are gathered and used for salads raw or dried to add to soup and stew.

0:40 #Czosnaczek

Just eat it eat it 😅

Thank you. Good job. Good perspective.

Ridiculous bull💩 the only invasion is from corporate filth.

aren't lamb's quarters native here in the US?

The blackberries are legendarily fierce here in the south end of the Willamette Valley in Oregon! We've learned to avoid the roadside brambles as too polluted by passing traffic – but no worries, there's tons more on any soil left fallow. I don't have the space to do canning in my place but I know plenty of neighbors who happily make lots of blackberry preserves and pies. <3

Mullein makes great toilet paper when out hiking.

You know red berries are likely to be poisonous in North America. So be careful.

Don't weed it! EAT IT!

Kudzu also makes a very fine high protein hay for cattle, goats and horses.

Thank you 👵🏻❣️

Invasive plants?? Your so calked list is what saved many lives from starvation! You're a goof ball.

Great video… Have subbed and look forward to more ideas! (I also like that you do this in short format, i.e. you get to the point!)

My ex made dandelion flower jelly this year. It was really good. I didn't get to try much of it though because my granddaughter ate it all up 😆

Live this! Thank you ❤

A friend made a very nice wine from autumn olive berries.

Here on the shores of the Puget Sound, I refer to the Himalayan Blackberry as Northwest kudzu.

the world is entropy…everything is invasive as weather changes..

I also discovered that Creeping Charlie is a good ground cover that keeps my roses pest free

Please make a video of plants in the high desert. Nevada, Oregon and Utah.

Did you realize that the art on the front of your video exploits the false stereotype that ET people are wanting to invade us? This is an insulting and rude visual slur, and if it’s an attempt at humor, it is not funny.

Every plant sold as a "solution" by IDIOTS who didn't do their homework has destroyed native vegetation and wreaked havoc.

BTW, we have a lot of Autumn Olive bushes but I have never seen any berries on them nor have I heard they were edible (since no one I know has seen berries on them). Maybe our silvery leafed bush is misnamed and belongs to another plant family.

Kudzu leaves may be edible, but they would be a famine food. They are almost impossible to choke down… especially not raw. Even the young leaves. Kudzu is best used as free goat food. Then eat the goats, I guess. Circle of life!

Goats adore removing any green leaf they can reach of blackberry.

Fact: Oregon, Washington, California, and British Columbia ARE the Pacific Northwest. Also fact, Himalayas are a challenge to control or remove, but the berries are delicious.

Im wondering if its necessary to mention for the average american to not eat mexicans.

That's crazy about the blackberries. In California up in the hills there are massive patches. And they taste deeper sweeter and have more flavor than any store bought ones. Now I know they aren't the same. Cool. Also they take over and die, then grow on top of their dead vines. Eventually leaving this massive thicket of blackberry choking out any competition. Some are 12 feet high and you can walk under the thicket.

You probably shouldn't be recommending people eat wild fennel without telling them how recognize it properly. If you eat the wrong plant you could die.

Purslane is my favorite wild edible and one of the healthiest for you.