✕

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed New York’s Central Park starting in the late 1850s, they created a set of diverse landscapes—including fields, meadows, lawns, and broad lakes. In the park’s upper reaches, they accentuated the existing topography, seeking to mimic the experience of visiting the Catskill or Adirondack Mountains, with rocky outcroppings, meandering streams, and wooded trails. Here, and throughout the park’s 843 acres, they hoped city residents would commune with nature, finding respite from the chaos of urban life. “What we want to gain is tranquility and rest to the mind,” said Olmsted in 1870.

Photo © Richard Barnes

Olmsted and Vaux probably never imagined that the rustic landscape near the park’s north end would one day be home to a chlorinated swimming pool with hundreds of kids boisterously splashing about. Nevertheless, during the summer months, if you take a 10-minute stroll from Fifth Avenue and East 106th Street, pass the manmade lake known as the Harlem Meer, and traverse a grassy hillock, that is exactly what you will find: children (as well as adults) bobbing in a vast oval-shaped pool—a marquee feature of Central Park’s recently completed Davis Center.

The project, paid for with $60 million from the city and $100 million raised by the nonprofit Central Park Conservancy replaces the Lasker Pool and Rink, a 1960s-era combined swimming and skating facility, which was well used by the surrounding community, but problem plagued. The old pool constantly leaked. Its brawny concrete structure had been seemingly muscled into what had been a ravine, without regard for the landscape’s topography or its hydrology. Built on top of a culverted stream that had connected a series of water features, Lasker impeded the supply of fresh water to the nearby Meer and would flood during rainstorms. It also disrupted a pedestrian route through the park. “Lasker was an object—a blockage,” says Susan Rodriguez, whose namesake architecture firm, in collaboration with Mitchell Giurgola Architects and the Conservancy, designed the Davis Center project.

The Davis Center seeks to address these problems—and more—with the aim of revitalizing the ecology of the long-neglected surrounding parkland, while sensitively integrating the recreational facilities into Olmsted and Vaux’s landscape. “That was the high-level idea behind the project,” explains Christopher Nolan, former chief landscape architect for the Conservancy.

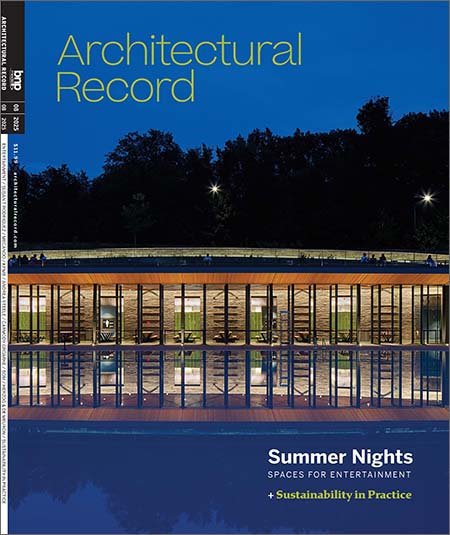

The Davis Center’s building is inserted into a hill along a park drive. Photo © Richard Barnes

In contrast to the imposing Lasker, the new 34,000-square-foot building, which houses changing rooms, a snack bar, and an indoor social space, is camouflaged. It has been carefully inserted into the snaking geometry of the park’s loop drive and partially submerged into a hillside. Covered with a meadow-like green roof of tall grasses and trees, including pines and oaks, park users who approach from certain directions may not realize there is a building there at all.

The pool itself, free of charge for all and managed by the city’s parks department, is an elegant ellipse, 120 feet wide and 285 feet long, with a capacity for 1,000 swimmers. Its predecessor was about 25 percent larger but had a more rounded ovoid shape (which some observers say resembled a toilet bowl). The new configuration is safer, says Rodriguez, since it is narrower, allowing lifeguards to quickly reach anyone in distress, she explains. It is also more accessible, with one end providing “zero entry,” where the pool bottom slopes gradually from the deck, allowing patrons with limited mobility to enter the water without negotiating stairs or ladders.

Like the old Lasker facility, the pool will transform to an ice rink during the winter months. But instead of sitting unused in the autumn and spring, it has been designed to be covered with a deck and artificial turf. During the shoulder seasons, this “Harlem Oval” provides space for lounging, picnicking, or group programming such as yoga. “It is three facilities in one,” says Rodriguez.

During spring and fall, the pool is decked over. Photo © Susan T Rodriguez Architecture

The building too will be open to parkgoers year-round. And though the structure seems hardly there at all from the outside, it is a stunner on the inside, with a 14-foot-tall social space opening out onto the pool deck via a series of full-height glazed pivot doors along its 150-foot length. The room’s lenticular plan is mirrored in the wood-baffled ceiling, where the outline of the triangulated trusses supporting the green roof above is traced. Sunlight streams in from a curved string of skylights, washing an arced wall clad in regionally sourced granite. Generously scaled portals open to a corridor leading to the changing rooms and other amenities, revealing deep-green ceramic tiles beyond.

1

The rich materials include regionally sourced stone (1 & 2) and green ceramic tiles (3). Photos © Richard Barnes

2

3

The just completed project includes repairing eight acres of the surrounding landscape, the last in a series of ecosystem-restoration efforts at the park’s northern end occurring over several decades. Part of the recent work involved repairing the site’s hydrology and reinstating a pedestrian route. A winding pathway now hugs the pool’s bermed western edge and, beside it, the once-buried stream, brought to the surface, gently flows.

A new pathway hugs the pool’s western bermed edge, reinstating a pedestrian route through the park. Photo © Richard Barnes

The landscape here has been conceived as “successional”—to evolve over time, says Nolan. At the stream edge, for instance, as trees mature, the ground cover will shift to more shade-tolerant species, making some areas more like woodland, he says.

Where the stream empties into the Meer, marshland plants help make the transition from brook to lake. A curving boardwalk wraps the water’s edge, supporting activities such as birding and fishing.

This final small piece is a microcosm of the ambitious Davis Center project, which provides ecological rehabilitation and creates space for recreation. “It is a constructed landscape,” says Nolan, “but one that allows city dwellers to reconnect to nature.”

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Susan T Rodriguez | Architecture • Design—Susan T Rodriguez, principal; Mikhail Grinwald, Sonia Flamberg, Amy Maresko, Josh Homer, George Switzer, Duncan White, Megan Friedman, project team

Architect of Record:

Mitchell Giurgola Architects–John Doherty, partner; Carl Gruswitz, project architect; Ying Xu, Colin Embrey, Karl Frantz, Angela Fisher, Jonathan Walston, Melida Marte, Catherine Vera, Plub Warnitchai, project team

Consultants:

LERA Consulting Structural Engineers (structure), Loring Consulting Engineers (m/e/p), Langan (geotechnical, site/civil); Stantec (rink/pool), Atelier Ten (sustainability), Werner Sobek (facades), Studio Sustena (green roof), Pine and Swallow (soils), Brandston Partnership (lighting)

General Contractor:

E.W. Howell

Client / Landscape Architect:

Central Park Conservancy–Christopher Nolan, chief landscape architect; Lane Addonizio, vice president for planning; Bob Rumsey, studio director for landscape architecture; Steven Bopp, project manager; David Turner, director of construction; Jacob Fiss-Hobart, project landscape architect

Size:

34,000 square feet

Cost:

$160 million

Completion Date:

April 2025

Sources

Cladding:

Champlain Stone, Berardi Stone, VM Zinc, Knight Wall Systems, Parex USA

Pivoting Wall System:

Roschmann, Keller

Interior and Exterior Glazing:

Eckelt, Tvitec, Reynaers, Vitro, TGP, Bendheim

Tile:

Heath Ceramics, Daltile

Hardware:

Schlage, LCN, Rixson, Tormax, CRL, Rockwood, Von Duprin

Lighting:

Electrix, A-Light, Presolite, Lumenspulse, Pathway Lighting, Gotham, Bega, SpecGradeLED, Lutron

Comments are closed.