For Controlled Environment Farms (CEF), the future of urban agriculture is not about a single farm or flagship building. It is about designing a distributed system. One where each facility contributes to a reliable, localized food network, guided by a centralized control layer and built for adaptability.

“CEF is developing a sensor monitoring system for both the nutrient water flow and environmental conditions within the growing capsule,” says founder Bruce Carman. “Both systems will take continuous measurements, in real time, and report the data to both the facility’s operational system and to CEF’s headquarters.”

What gets measured gets managed

Each CEF site includes sensors that monitor macro- and micronutrients, dissolved oxygen, pH, and ammonia in the nutrient flow system. In parallel, the environmental conditions inside each capsule, such as temperature, humidity, and CO2, are continuously tracked. “The measurements taken are then used to make real-time adjustments in each system as required,” Carman explains.

While the company is still finalizing its proprietary software, CEF is working with two external developers. “The specifics of each are not available until IP protection is secured,” he says. Long-term, both AI and robotics will play key roles in optimizing the system. “CEF is moving forward with facilities that will be completely autonomous,” says Carman. “As labor shortages and costs continue to rise and climate change affects traditional farming methods, the need for change is apparent.”

From proof of concept to a resilient network

In practice, each CEF site is staffed by an operator who oversees local activities like germination, cultivation, harvesting, processing, packaging, and distribution. Meanwhile, a regional HQ operator manages multiple sites across a geographic area. © Bruce Carman

© Bruce Carman

“The HQ operator oversees operations for several facilities that are typically related to one another through geographical placement. The importance of this relationship is redundancy,” Carman explains. “Should an issue arise at one facility, the HQ operator will have the information required to adjust systems at other facilities to ensure customer demands are met.”

“Delivering products with consistent quality, quantity, and pricing is the business model for CEF,” he adds. This layered structure, local execution with centralized oversight, is designed to ensure continuity and food security, especially in urban food deserts.

Adapting infrastructure to fit the capsule model

Every facility begins with a thorough inspection. “Each existing facility must undergo an environmental assessment for food safety compliance,” says Carman. “All aspects of the building are inspected to make sure the structure is safe and does not contain remnants from previous occupancies that are not conducive to safe and secure food production operations.”

Costs vary depending on structural remediation and production goals. “In most cases, existing buildings can start operations in one year and reach 100 percent performance in two years,” he says. Currently, CEF is working with two SCORE Business Mentors to build out its proof of concept and HQ in Northern Illinois, with possible expansion into Chicago. “Once completed, we will expand operations to food desert locations in other communities,” Carman explains. “Creating a sustainable, non-polluting business with sustainable jobs for that community.”

Purpose-built structures and shared systems

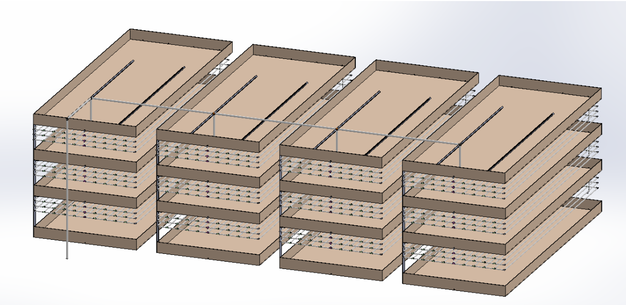

New builds will follow a multi-level format. “The CEF prototype or ‘new build’ is a three- to four-level building specific to urban agriculture,” Carman explains. “Its structure, methods, and systems housed within are engineered specifically for CEF’s method of flood and drain aquaponics.”

Each floor is designed to take advantage of natural forces to reduce operational costs. Tilapia tanks on the ground floor are heated to 75–80°F, creating warm, humid air that rises through perforated floors to support upper-level plant growth. This stratified airflow creates a “chimney effect” that enables passive climate zoning across the second, third, and fourth floors.

“Lettuce is cultivated on the cooler second floor, eggplant on the warmer third, and tomatoes and basil on the fourth,” Carman explains. “This natural stratification reduces HVAC loads and lets the building itself do much of the climate work.”

At the same time, gravity supports a tiered nutrient delivery system. Water pumped to the top floor begins at full nutrient concentration, then flows downward as each crop tier absorbs what it needs. By the time it returns to the aquaculture tanks, the water has been filtered and naturally depleted, ready to re-enter the closed-loop cycle.

“Nutrient water at full concentration is pumped to the top floor and gravity-fed downward,” says Carman. “Each crop tier absorbs nutrients appropriate to its needs, and by the time the water reaches the fish tanks again, it’s been filtered and depleted naturally,” CEF reports that a fully operational prototype facility can generate up to $16 million annually in produce revenue, with each 100-foot growing trough accounting for roughly $1 million per year.

© Bruce Carman

© Bruce Carman

Toward a mature food system

CEF’s long-term vision centers on building resilience. Rather than relying on centralized mega-farms or distant food imports, the company wants to enable local systems that can scale without compromising supply.

“CEF’s long-term vision is to see urban agriculture and food production at a level that eliminates the need for food to travel long distances to the consumer,” says Carman. “To accomplish food security, at least two facilities would be needed. Each facility is capable of cultivating what the other facility does. This would be the cornerstone of a mature food system.”

For more information: Controlled Environmental Farming

Controlled Environmental Farming

Bruce Carman

+1 (218) 370 2005

[email protected]

Comments are closed.