“Everyone loves Fumio,” says Shinya Ueda of his 74-year-old father and mentor. That’s because beneath Fumio Ueda’s wise smile and friendly, respectful demeanour for which he is known by his clients, he is a precious living embodiment of a fierce Japanese artform more than 1000 years old; a master Japanese gardener. His mind a textbook.

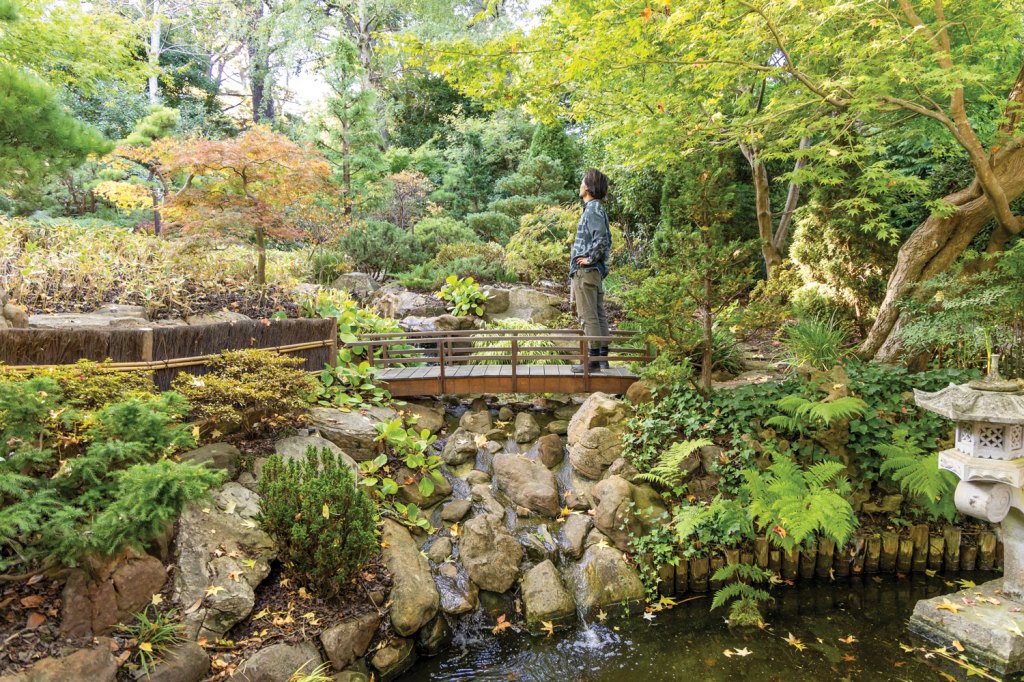

Of all Fumio’s work, his key legacies include the Adelaide Himeji Garden, of which he oversaw its redevelopment in 1998, and a special Japanese section of the private and historic Adelaide Hills residence, Thorpe Estate. The latter is where SALIFE meets father and son on a pleasant autumn afternoon.

Fumio was contracted to design and landscape this section of the garden in 2001, bringing in 50 tonnes of rock to emulate a traditional mountain-scape garden. More than two decades later, he and Shinya, who is now a second-generation master Japanese gardener, continue to maintain it.

Shinya turns on a water pump that unleashes a stream from the top of a man-made creek, trickling down the sloping garden, criss-crossing beneath paths and autumnal gold foliage of manicured pine trees and Japanese maples. An arched wooden bridge leads down to a waterfall and pond, overlooked by an azumaya timber pavilion – a place of contemplation.

Just like the principles of bonsai, a Japanese garden is carefully cultivated to create an aesthetic that looks natural by design. Man-made elements – such as sculptures, bridges and other structures – are key.

Shinya says that this garden is one of the most authentic Japanese gardens in Australia.

“It’s not the biggest Japanese garden, but it is authentic; it has soul,” says Shinya.

“It’s fantastic that the client Stephen Lake entrusted Fumio and the late carpenter Ian McPherson to create this special garden. Without Stephen’s vision and Ian’s craftsmanship, this garden would never have come to life.

In 2001, Fumio began working to create the garden and its various structures with the late carpenter Ian McPherson.

In 2001, Fumio began working to create the garden and its various structures with the late carpenter Ian McPherson.

“Some of the trees are still considered juveniles. The best Japanese gardens are in Japan – they have a few hundred years’ head start with things you can only make with time, such as ancient pine trees.”

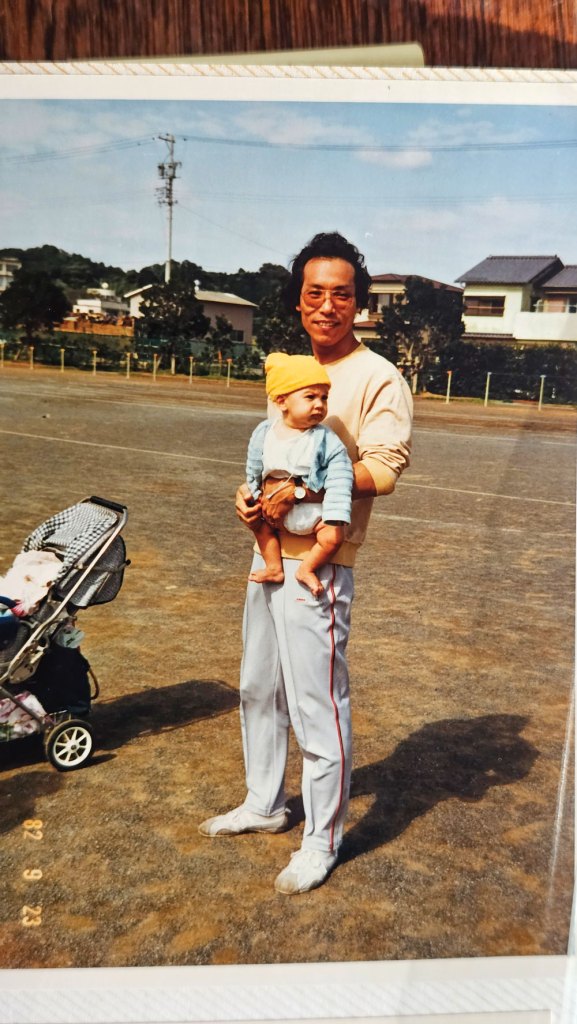

Fumio was born in 1951 in Shizuoka City, known for its traditional Japanese gardens and displays of cherry blossoms, hydrangeas and wisteria. His first job was working in a record shop during the vibrant cultural renaissance of post-war Japan. Fumio grew his hair long, all the way down his back, and left Japan at 27 on a sabbatical, hitchhiking the world for three years. It was in Nepal that Fumio met his wife Jayne – a South Australian – and the couple moved to Japan and started their family.

Fumio cut his hair – shedding his “hippie” look – to get a job.

Fumio, 74, hails from Shizuoka City where he trained to become a master Japanese gardener.

Fumio, 74, hails from Shizuoka City where he trained to become a master Japanese gardener.

“When I was 33 years old, I was trying to find some work that I could do for the rest of my life. I wanted to be a gardener, a farmer or a teacher. I was too late to become a teacher, I didn’t have any land to be a farmer, but I could be a gardener,” says Fumio.

Fumio started an apprenticeship with third-generation master Japanese gardener Toshio Hirai and, as is traditional for learning a trade in Japan, the initiation was punishing at times.

“I could handle the harder conditions in the apprenticeship because it was enjoyable work. A few times, I nearly clashed with the boss, but I wanted to continue,” says Fumio. “When I was an apprentice, in the beginning of my gardener life, I didn’t think of a garden as an artform, but now I understand; it’s creation. My master always said, ‘observe, observe, because everything is there in front of you’.”

Shinya Ueda stops to observe the Adelaide Hills Japanese garden which his father Fumio designed in 2001, and which the pair continue to maintain.

Shinya Ueda stops to observe the Adelaide Hills Japanese garden which his father Fumio designed in 2001, and which the pair continue to maintain.

In 1991, Fumio and Jayne moved to South Australia with their two children.

“It was very difficult in the beginning, because no one knew me or what I could do,” he recalls. “There was a recession in Australia, so there were no jobs and it was a hard time for a few years.”

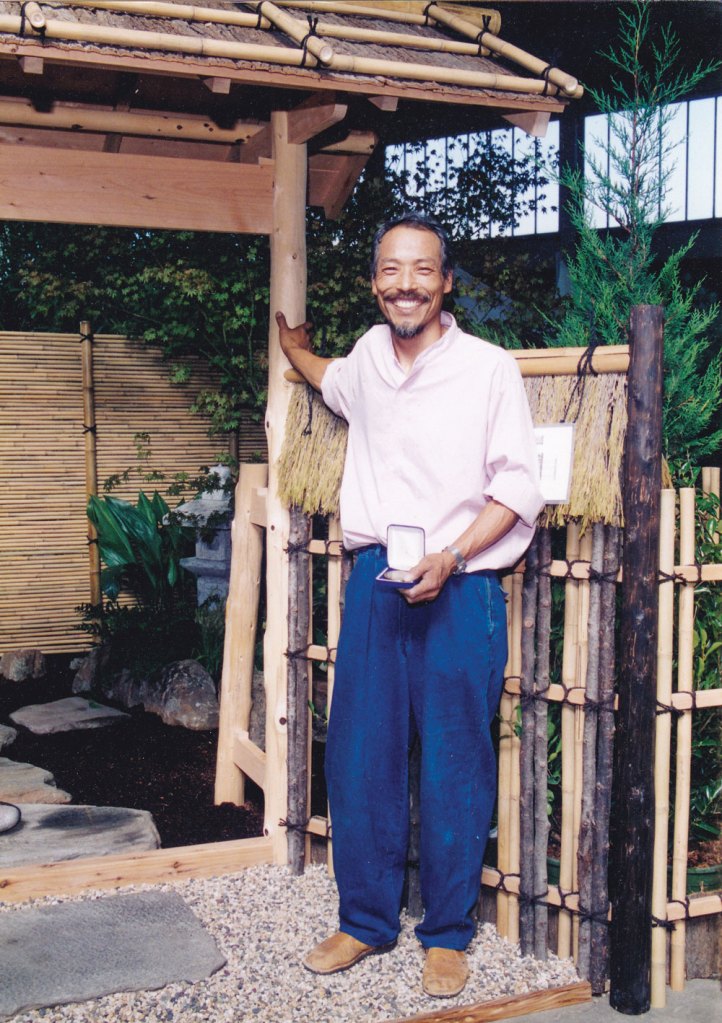

Attention from local ABC gardening programs helped to raise Fumio’s profile. He was called upon to oversee the redesign of Adelaide’s Himeji Garden and became known as one of a select few Japanese garden experts in Australia.

Meanwhile, Shinya left Adelaide for Japan at 19 and became an apprentice under a renowned artist, Yoshiaki Yuki, at his studio and gallery nestled in the mountains. The experience taught him how Japanese art and design integrate with nature.

“Art, design and craft are delineated in the West, but in Japan, they’re more integrated; it’s not as rigid,” Shinya explains.

He then worked at an art gallery in New York City, before moving back to Adelaide.

An azumaya timber pavilion provides a place to sit and contemplate the garden within the private Thorpe Estate.

An azumaya timber pavilion provides a place to sit and contemplate the garden within the private Thorpe Estate.

“I didn’t want to work in an office again. In 2012, Dad needed help with a project, so I started working with him, and I thought: ‘This isn’t bad’. He was about to retire and was thinking of cutting back, but I’ve dragged him out of retirement,” says Shinya.

“I was lucky. In Japan, you can’t just start working for a master and expect to be able to work on the important trees in the first few years. Sometimes I’d look at the branches Fumio had worked on and go: ‘Oh, that’s how he’s done it’. It’s not like study; there’s no book for it. It’s an esoteric knowledge. Fumio let me make mistakes and that expedited the learning process. I was hungry, so I did a lot of my own research.”

In more than a decade of working together, Shinya and Fumio have developed a layered relationship. Shinya has observed how his father’s style has evolved over time, learning not only about Fumio as a father, but as a creative person.

Fumio holding Shinya in Japan, 1982

Fumio holding Shinya in Japan, 1982

“We all grow up and start to see our parents as humans, but I’ve got another layer having intimately worked with Dad,” says Shinya. “I get to appreciate his sensibility. Through studying the trees he’s created, I can get into his mind.

“His style has changed over the years. He’s 74 now, and I notice that the cuts are becoming gentler. In contrast, my cuts are still uncompromising. I went through a phase of being obsessed with his work, emulating that as much as I could. Then, I went through a phase of challenging and trying different ways, and now I’m at a phase of appreciation. We’re at a very interesting place, not just as father-and-son, but as gardeners.”

Fumio is proud of how his son has worked to develop his style, knowledge and creativity, building on the artistic sense that he developed in Japan. Working with his son has motivated Fumio to keep going in his mid-70s.

“I don’t want to stop, but of course at this age things get harder – up on a ladder, or heavy lifting,” Fumio says. “I can’t do that now. But I want to continue, even if it’s just one hour a day, until my body gives up. I think I’m very lucky, because when tradesmen work with their son, it mightn’t always go as well.

Fumio winning first prize at an Adelaide horticultural show in 1996.

Fumio winning first prize at an Adelaide horticultural show in 1996.

“Now Shinya is designing gardens, I’m very interested in his work. He has a very different view with his garden design and I am very happy that he is exploring and expanding his knowledge. The most important part of Japanese garden design is composition. When I plan a garden, if one thing changes, everything changes. Garden is art that keeps on growing.

“As a gardener and a creator, I’m always looking for new material, not only plants but also structure. Unlike a painting or sculpture, the garden is always changing. I enjoy that.”

Shinya is now working on large-scale projects. Currently, he is designing the world’s largest wisteria tunnel at Mayfield Garden in New South Wales, and is also consulting to Adelaide Botanic Garden. While looking to the past for inspiration, he is also looking to the future.

A young Shinya with mum Jayne, sister Maya and dad Fumio.

A young Shinya with mum Jayne, sister Maya and dad Fumio.

“Showing that these beautiful Japanese gardens can be created here in Adelaide is the legacy that Fumio has created,” Shinya says. “But, going forward, we as Japanese gardeners in Australia ask the question: what is an Australian garden? Is it just whacking in native plants? I don’t think so.

“Japanese culture is in a stage of refinement. And conservation of culture is how you honour the ancestors. But here in Australia, where the culture is still very dynamic, I want to honour the ancestors, through Fumio, while honouring this culture too.”

Shinya says he and Fumio honour their ancesters through preservation of culture, while also working to push the boundaries of what an Australian garden might be.

Shinya says he and Fumio honour their ancesters through preservation of culture, while also working to push the boundaries of what an Australian garden might be.

As Shinya and Fumio lead SALIFE deeper into the garden, occasionally stopping to observe the progress of the plants and trees, they seem at home: as if they themselves belong to the garden, like the statues, paths and structures around them.

“As you see here, you’ve got to put the human element into the garden: the tea house, the bridge and the lanterns. Integrating our human presence into the natural space. If you take all of that away, it’s just trees and rocks,” says Shinya.

“We are not separate to nature; we have a place in that story. We’re as organic as the plants.”

This article first appeared in the June 2025 issue of SALIFE magazine.

Comments are closed.