When concerns surfaced that the redesign of Tom Lee Park would only benefit downtown, the firm returned to the drawing board.

By Gale Fulton, ASLA

What is the agency of the urban designer? How do we not just make landscapes, buildings, and public space, but make change?” These provocative questions, set out by Kate Orff, FASLA, and SCAPE in their 2016 book, Toward an Urban Ecology, guide the firm’s work while serving as a call to action for designers of the built environment. Almost 10 years later, the redesign of Tom Lee Park in Memphis, Tennessee, by SCAPE and Studio Gang can be viewed as a case study in how these questions have and haven’t been answered. The project won a 2024 ASLA Professional Honor Award in General Design.

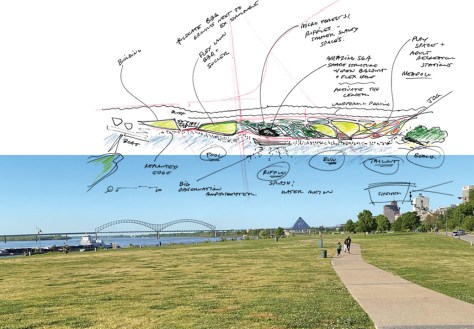

TOP: Early conceptual sketches of the park were informed by the dynamics and features of the Mississippi River and programmatic requirements. Image by Kate Orff, FASLA. ABOVE: Prior to the SCAPE and Studio Gang redesign, the park was largely a treeless, featureless lawn that provided little incentive for residents to visit. Photo by SCAPE.

TOP: Early conceptual sketches of the park were informed by the dynamics and features of the Mississippi River and programmatic requirements. Image by Kate Orff, FASLA. ABOVE: Prior to the SCAPE and Studio Gang redesign, the park was largely a treeless, featureless lawn that provided little incentive for residents to visit. Photo by SCAPE.

The park opened in September 2023 after roughly four years of planning, designing, conducting community meetings, fundraising, and overcoming contentious opposition by some to the proposed redesign. The radical reworking of Tom Lee Park is a concrete example of how designers can meaningfully contribute to a more robust urban ecology and how landscape and its designers can create socio-ecological change. Reflecting on the project’s evolution, SCAPE’s founder Kate Orff emphasizes how the city’s history and configuration forced the team to adapt its way of working and thinking about the potential of the park. “I learned so much from working in Memphis,” she says, including “the need for more radically welcoming people.”

The site of the park has undergone three major changes in the past 100 years. Before the creation of Riverside Drive, which separates the city from the Mississippi River, it was effectively a dumping ground for residents and businesses, a history not unlike that of many urban riverfronts across the United States. When Riverside Drive opened in 1935, it not only provided an important transportation corridor for the city but also partially served as a bluff stabilization tactic. Throughout this period, Tom Lee Park, then called Astor Park, was little more than a small patch of grass between the Mississippi River and Riverside Drive.

Installation of stone in the cut-bank bluff. Photo by SCAPE.

Installation of stone in the cut-bank bluff. Photo by SCAPE.

In 1954, the park was renamed Tom Lee Park as a tribute to Memphian hero Tom Lee, an African American man who, despite not being able to swim, risked his life by rescuing 32 of the 72 passengers who were thrown into the cold, strong currents of the Mississippi when their ship capsized on May 8, 1925. Memphis parks and other public amenities were segregated until 1963, and the city had a long history of enforcing Jim Crow laws and resistance to those laws by Ida B. Wells and others.

The park was expanded in 1991 when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers added roughly 31 acres to further stabilize and protect the nearby bluff from the fluctuations of the Mississippi River. At this location, the river averages about half a mile in width, and its height can easily fluctuate as much as 50 feet annually, even occasionally overspilling its banks and reaching the level of the park, as it most recently did in 2011 when the river reached its highest level since 1937.

The bluff provides a fully accessible entryway to the park from the neighborhoods above. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The bluff provides a fully accessible entryway to the park from the neighborhoods above. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The Army Corps project, approximately 360 feet wide at its broadest point from the shoulder of the riverbank to Riverside Drive, created a 150-foot-high dike wall backfilled with sand dredged from the river, which was then capped with three feet of clay. This resulted in a large, compacted open lawn with some on-site parking and no more than 50 trees across the entire site, many of which struggled to stay alive. The dearth of trees meant that the park offered virtually no shade across its 31 acres in a city that averages temperatures in the upper 80s to mid-90s throughout the summer months. Climate change projections suggest it could be one of the hottest cities in the United States in the next 30 years.

In 2006, the Tom Lee Memorial sculpture by David Alan Clark was dedicated to further honor Lee’s actions. It was sited near the north-south center of the site near the shoulder of the dike, which allowed visitors to look out onto the river as a backdrop for Tom Lee’s rescue of the M. E. Norman’s passengers, but even this additional element did little to increase the park’s usage. Carol Coletta, a longtime Memphis resident and the former president and CEO of the Memphis River Parks Partnership, a nonprofit public-private partnership, said that the park used to be primarily thought of as a place for fireworks shows or other one-off events, such as the annual Memphis in May festival, but it was never really a place for regular use, in part because it was almost completely devoid of features, amenities, or even trees.

Studio Gang’s Sunset Canopy provides a dramatic setting for basketball and other activities. The canopy was dedicated to Tyre Nichols, a Black man and Memphis native killed by Memphis police in January 2023. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

Studio Gang’s Sunset Canopy provides a dramatic setting for basketball and other activities. The canopy was dedicated to Tyre Nichols, a Black man and Memphis native killed by Memphis police in January 2023. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

In 2017, Studio Gang was hired by the mayor’s Riverfront Task Force to rethink a six-mile stretch of the riverfront. The resulting plan, the Memphis Riverfront Concept, describes five zones, including Tom Lee Park. SCAPE was brought on as the landscape architects.

This ensemble of sculpture and landscape

is already powerful.

Early sketches for the organization of the park by Orff drew inspiration from the natural dynamics of the river. Riffles, pools, eddies, and tailouts inform the early bubble diagram about potential park programming. A subsequent sketch shows how these river analogs might further guide both the form and program of the park. Large lawn spaces equate to pools, the pathways represent the turbulent and striated nature of riffles, and the tailout area at the southern end of the park becomes the place that collects the greatest density of ecological habitat.

But a key inflection point for the design evolution of the park came at a council meeting when Orff was asked, “Is this a park for downtown, or is this also our park?” Representatives of districts further to the south and east of downtown were uncertain how the park was being conceptualized, and there was a perception that the park was primarily to be an extension of downtown rather than a space that invited all Memphians to the waterfront. Orff says this meeting triggered what she fondly recalls as the “micro-deltas moment.”

Multiple soil profiles were developed to support the unique characteristics of the different zones on-site. Photo by SCAPE and John Donnelly, ASLA.

Multiple soil profiles were developed to support the unique characteristics of the different zones on-site. Photo by SCAPE and John Donnelly, ASLA.

Orff, determined to make a park for the entire city, not just those living in or visiting downtown or the wealthy property owners on the bluff overlooking the park and river, realized a new approach was required. She told the SCAPE team, “We have to change how we’re thinking about the park entrances…there have to be multiple parks along this long, 30-acre line.” The team began to think of a series of “micro-deltas,” effectively microparks within the larger 30-acre park. This reconceptualization changed the idea of the park from the somewhat traditional concept of a linear park—made up of “rooms,” accessed from a main entrance near downtown, and traversed linearly—to what Orff refers to as five different parks, “each with an entrance that is directed toward a different kind of community.” This shift is discernible when comparing Orff’s early sketches with the final illustrative plan. The micro-deltas are clearly articulated in relationship to the primary routes from the city into the park. Orff says this change in thinking helped the team reconsider the overall scale of the park and add detail, complexity, and greater topographical diversity to the park design.

Beyond this guiding metaphor, the layout of the park was greatly conditioned by the form and function of the earlier bluff stabilization work by the corps, which constrained the design possibilities throughout the park to maintain the integrity of the corps’s structure. A 150-foot span across the center of the park was established in which no cut or fill was allowed, while in an area near Riverside Drive, no cut was allowed, but the designers could add fill to build topography as they saw fit. This flexibility near the road allowed the team to strategically build up topography to create separation from the road in some areas while preserving views from the road across the park to the river in others. This topographic variation, combined with a complex multilayered planting plan, creates significant spatial diversity across the site.

The view from A Monument to Listening to the site’s earlier memorial to Tom Lee and the Mississippi River beyond. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The view from A Monument to Listening to the site’s earlier memorial to Tom Lee and the Mississippi River beyond. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The final plan shows the site broken into four zones on its long, roughly north-south axis: Civic Gateway, Active Core, Community Batture, and Habitat Terrace. As the names suggest—other than Community Batture, perhaps—these zones are programmatically differentiated. The formal and spatial characteristics of each zone are also unique and further diversified by distinct planting approaches. Civic Gateway is composed of the Autozone Plaza and the beautiful cut-bank bluff, which allows for a fully accessible route down to the park from the bluff across Riverside Drive. Informed by the regional geology of cut-bank bluffs, the site is benched with stone that changes in color from grayish near the bottom to rusts and browns near the top.

Active Core contains large lawn areas, the Sunset Canopy and the colorful basketball courts beneath it, and a large playground with oversized play structures inspired by the fauna of the Mississippi River, such as otters, sturgeon, and salamanders. Large areas of lawn in Active Core are, in part, a compromise reached with supporters of the annual Memphis in May festival that has historically taken place at Tom Lee Park. As part of a mediation agreement entered into by the City of Memphis, the Memphis in May International Festival, and the Memphis River Parks Partnership, three areas of lawn were among the elements that had to be accommodated by the design team. These lawn areas—outlined in the agreement as North, Middle, and South and which were required to be no less than 67,000, 100,000, and 82,000 square feet, respectively—seemed oversized and underused during site visits, but regular users report that these areas do see periods of more intense use depending on season, weather, and weekend versus weekday. Perhaps ironically, the Memphis in May festival no longer takes place at Tom Lee Park.

One of many ways to relax at Tom Lee Park in Memphis. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

One of many ways to relax at Tom Lee Park in Memphis. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

Community Batture is likely the most contemplative space, largely because of A Monument to Listening, a large-scale installation by the artist Theaster Gates composed of 32 separate sculptures representing the number of lives saved by Tom Lee, plus a 33rd sculpture that stands apart from the others to inspire contemplation of Lee’s selfless efforts. Gates’s work looks out across the park to the original Tom Lee sculpture and across the Mississippi, a purposeful visual conversation. The design team enhanced the connection by wrapping the back of the piece into a grove of densely planted river birch. Not even two years since its completion, this ensemble of sculpture and landscape is already powerful, and it will likely become more poignant as the birches age and enclose the space even more. It’s hard to overstate the profound impact that Gates’s “anti-monument,” as he has referred to it, has on its subject, and the additional dimension it adds to the overall experience of the site.

Students visit the park for hands-on engagement with ecological concepts and phenomena.

The last of the named areas is Habitat Terrace, located in the southernmost section of the site adjacent to the neighboring Ashburn-Coppock Park. This is the smallest of the zones by area but contains interesting programmatic and functional elements, including a high-performance ecolawn and small areas for visitors to gather around and observe habitats and ecological processes. The ecolawn might best be understood as an ecological experiment undertaken by SCAPE and the Memphis River Parks Partnership as a progressive strategy to meet the need for lawn space but challenge the traditional high-maintenance, low-biodiversity qualities of lawns. Hardy low-maintenance species such as sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), sheep fescue (Festuca ovina), red fescue (Festuca rubra), fewleaf sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis), and prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata) provide casual visitors and focused students with a vivid alternative to the typically toxic American lawn.

An outdoor classroom in the Habitat Terrace allows visitors to pause and study the new ecology of the site. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

An outdoor classroom in the Habitat Terrace allows visitors to pause and study the new ecology of the site. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The material and detailing feel appropriate for a public park that is expected to receive a large number of visitors throughout the year. The stone used in the cut-bank bluff is repeated throughout the site for terracing, steps, and other details. Wood decks and benches are constructed to be easily replaced locally if damaged. Fencing materials are also designed with a similar ethos, and their simplicity allows visitors to focus on the complex plantings that they often protect. According to Brad Howe, a principal at SCAPE, the team’s strategy for detailing was really about “durability and simplicity” and to “develop a series of solid, clear, and simple details that could be repeated across the park,” which would stand up to both environmental conditions and intensive public usage.

In contrast to the elegant simplicity of much of the hardscape details, the plantings are multilayered and complex. Planting plans used a range of mixes, including riffle mix, thicket mix, tallgrass prairie mix, and riparian mix. They serve as the background matrix for additional layered plantings of shrubs and trees. The result is a series of planting zones that are literally packed with natives, such as little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), button eryngo (Eryngium yuccifolium), and wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), to name only a few of the species in the tallgrass mix. Given the relatively poor track record for complex ecological plantings in public parks, it remains to be seen if these plantings will be stewarded beyond initial establishment so that the full effect of the intended complexity is realized.

The plantings are warrantied for the first two years and are the responsibility of the contractor, but after that, a robust maintenance plan will need to be implemented to avoid the decline often seen in such landscapes. Coletta says that the Memphis River Parks Partnership will be able to draw lessons from other park projects it maintains. John Donnelly, ASLA, SCAPE’s technical principal and partner, said that they have been actively monitoring the plantings even in the first year to advise the contractors on management. For Donnelly, these types of projects suggest the need for an approach akin to gardening in which the different zones are assessed for how species are responding, moving, and evolving and then adaptively managing them to achieve the desired aesthetic and ecological effects.

A view of the Active Core, with playground structures in the foreground and basketball courts under the Sunset Canopy near the river. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

A view of the Active Core, with playground structures in the foreground and basketball courts under the Sunset Canopy near the river. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

In addition to what may be considered the more traditional formal, spatial, and programmatic aspects of a park, the design team also worked with Memphis schools to create a curricular component that has been adopted across the Memphis-Shelby County school system, a joint city/county school district that is the largest in Tennessee. Students in third and ninth grades visit the park as a formal part of their curriculum for hands-on engagement with ecological concepts and phenomena. This program has resulted in thousands of students (10,000 in one semester, according to Coletta) visiting the site each semester to learn about topics such as air quality and noise pollution, the ecology of the region, specific planting strategies and materials, and the impact urban environments can have on watershed systems such as the Mississippi. Howe calls the curriculum component of Tom Lee Park a “vector for ecological thinking,” and says that along with the design ethos developed with Studio Gang, it is a way to “educate students in Memphis about these more critical landscape topics that can contribute to the overall resilience of their city.”

The redesigned Tom Lee Park cost approximately $61 million. In addition, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation provided a $1.4 million grant to support the Monument to Listening art installation by Gates. While there are obvious areas where the team clearly assumed disciplinary roles, Orff says that concerns of authorship or territoriality were never a part of the process because the project stemmed from a “community ethos” that was “about Memphis.”

“You have to go beyond just opening the fence;

you really have to reach out to people.”

—Kate Orff, FASLA

In reflecting on the park’s potential impact, Orff notes that she was influenced in her thinking by Mitchell Silver, Honorary ASLA, an urban planner and the former commissioner for the New York City Parks Department, and Maurice Cox, an architect and urban planner, among others, and that the team was guided by the notions that “you have to go beyond just opening the fence; you really have to reach out to people.”

The park provides the setting for stunning views of sunset across the Mississippi. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The park provides the setting for stunning views of sunset across the Mississippi. Photo by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

“This park is bigger than anybody working on it because Memphis needs this park,” Orff says. “The whole park is an invitation to make new memories and to have new experiences.”

Gale Fulton, ASLA, is the director of the School of Landscape Architecture at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Project Credits

Co-Design Lead/Landscape Architect SCAPE Landscape Architecture, New York City. Co-Design Lead/Master Planner/Architect Studio Gang, Chicago. Client Memphis River Parks Partnership, Memphis, Tennessee. General Contractor Montgomery Martin Contractors, Memphis, Tennessee. Landscape Contractor Rotolo Consultants, Inc., Slidell, Lousiana. Civil Engineer Kimley-Horn, Memphis, Tennessee. Structural Engineer Thornton Tomasetti, Chicago. M/E/P Engineer Innovative Engineering Services, Memphis, Tennessee. Sustainability Analysis DataBased+, Chicago. Lighting Randy Burkett Lighting Design, St. Louis. Artist Theaster Gates, Chicago; James Little, New York City. Playground Designer Monstrum, Copenhagen, Denmark. Ecological Consulting Applied Ecological Services, Brodhead, Wisconsin (now part of Resource Environmental Solutions, Houston). Fountain Consultant Delta Fountains, Jacksonville, Florida. Soils Consultant Olsson, Oakland Park, Kansas. Irrigation Consultant Hines Inc., Dallas.

CORRECTION: The print version of this article mixed up the job titles of Brad Howe and John Donnelly, ASLA, at SCAPE. The error has been corrected here.

Like this:

Like Loading…